Creativity as Archaeological Discovery: Systematic Exploration and Refinement

The most profound implication of Dr. George Newman's insights into creativity is that the widely held belief in the solitary genius and the spontaneous "light bulb moment" is not only inaccurate but actively hinders our ability to generate truly valuable ideas. Instead, creativity is presented as a deliberate process of discovery, akin to archaeological exploration, where ideas are unearthed rather than conjured. This reframing reveals hidden consequences: clinging to the myth of innate genius leads to passive waiting and missed opportunities, while embracing the exploration model empowers anyone to become a more effective idea generator. Those who grasp this shift gain a significant advantage by actively engaging with the world to find and refine novel solutions, moving beyond the frustration of creative blocks.

The Myth of the Lone Genius: Unearthing Ideas in the World

The pervasive narrative of creativity centers on the solitary genius, a figure waiting for a divine spark to ignite a brilliant idea. This image, deeply ingrained in our culture, suggests that creativity is an innate, mystical talent bestowed upon a select few. Dr. George Newman, however, argues forcefully against this romanticized notion, reframing creativity as a process of discovery and exploration, much like an archaeologist excavating a site. This distinction is crucial because it shifts the locus of creativity from an internal, elusive wellspring to an external, accessible landscape. The consequence of clinging to the "lone genius" myth is a passive stance, where individuals wait for inspiration rather than actively seeking it. This leads to a cascade of missed opportunities, as potential ideas lie dormant, undiscovered.

Newman's research highlights "hot streaks," periods where creators in various fields produce their most impactful work in rapid succession. This phenomenon, as observed in artists like Jackson Pollock, suggests that intense periods of exploration precede breakthroughs, rather than spontaneous generation. The idea of parallel discovery, where multiple individuals independently arrive at similar ideas concurrently, further undermines the lone genius theory. This suggests that ideas are not solely "brain-born" but rather exist in the environment, waiting to be found. Thomas Edison, often cited as the archetypal inventor, exemplifies this. Despite his association with the light bulb, his success stemmed from extensive team-based exploration and borrowing from existing work, not solitary inspiration.

"My so-called inventions already existed in the environment. I took them out. I created nothing. Nobody does. There's no such thing as an idea being brain-born. Everything comes from outside."

-- Thomas Edison

This perspective offers a powerful advantage: by understanding that ideas are external and discoverable, individuals can actively engage in practices that increase their chances of unearthing them. The immediate payoff of this shift is the dispelling of the myth that one must be a naturally gifted genius to be creative. The longer-term advantage lies in developing a systematic approach to idea generation, leading to more consistent and impactful innovation. Conventional wisdom, which emphasizes solitary introspection and waiting for inspiration, fails when extended forward, as it offers no practical mechanism for consistent idea generation.

Surveying the Landscape: The Power of External Input and Sociability

The first practical step in this archaeological model of creativity is "surveying"--understanding the conceptual landscape. This involves orienting oneself, identifying where good ideas have been found in the past, and seeking out promising areas for exploration. A critical insight here is that this process is inherently social and outward-looking, directly contradicting the myth of the isolated creative mind. Newman points out that even figures like Thoreau, often depicted as hermits, were deeply connected to their communities, hosting parties and engaging with others. This highlights a profound downstream effect: isolation, while seemingly conducive to deep thought, actually limits exposure to the diverse inputs that fuel creativity.

The implication is that social interaction and exposure to new environments are not distractions but essential components of the creative process. New people, new surroundings, and even new music can act as triggers for novel ideas. This challenges the conventional wisdom that one must retreat from the world to be creative. The advantage of embracing this outward orientation is that it leverages the collective intelligence and varied experiences of others. It also suggests that feeling "stuck" might be a signal to broaden one's environmental inputs rather than to intensify solitary effort. The exploration of external sources -- from conversations to the environment -- becomes the primary mechanism for generating novel concepts.

"Even new pictures on the wall, new kinds of furniture, and exposure to new people can be that trigger which cues a new idea."

-- Dr. George Newman

Furthermore, the concept of "emulating" or the "5% novelty rule" suggests that complete originality is not the goal. Instead, building upon existing ideas with a small but significant twist--finding that additional 5%--is a powerful and accessible route to creativity. This demystifies the creative process, making it less about inventing something from nothing and more about skillfully remixing and refining what already exists. The hidden consequence of pursuing absolute originality is often paralysis; embracing emulation, conversely, facilitates progress by providing a clear, actionable path forward.

Gridding for Insight: Embracing Constraints and Systematic Exploration

The second stage, "gridding," involves systematizing the search for ideas. This means keeping track of where one has explored and, crucially, where one hasn't. This systematic approach, much like archaeological gridding, ensures that the search is thorough and that no promising areas are overlooked. A key insight here is the radical notion of "thinking inside the box." Instead of striving to break free from limitations, Newman advocates for embracing and utilizing constraints as powerful catalysts for creativity. This directly challenges the common advice to "think outside the box," which often leads to unfocused and unproductive brainstorming.

The downstream effect of embracing constraints is the generation of more focused and often more impactful ideas. When faced with limitations, such as Matisse's bedridden state due to surgery, creators are forced to innovate within those boundaries, leading to entirely new methods and styles. This principle extends to "transplanting"--taking principles from one domain and applying them to another. The redesign of the bullet train's nose cone, inspired by the kingfisher's beak to solve the sonic boom problem, is a prime example. This demonstrates that constraints, when creatively harnessed, can lead to elegant and unexpected solutions. The advantage of this approach is that it transforms perceived weaknesses into sources of strength, fostering resilience and ingenuity. Conventional wisdom, which often views constraints as obstacles to be overcome, fails to recognize their generative potential.

"I talk about the way in which creativity really responds to not only what's in our environment, but what about the environment is limiting our idea. And when we can take those limitations and use them to our advantage, it's actually can be a very powerful source of creativity."

-- Dr. George Newman

The systematic nature of gridding, guided by a clear "guiding question" (What am I trying to do and why? Who is this for?), ensures that the exploration remains targeted and valuable. This prevents the aimless wandering that often characterizes unfocused brainstorming. The hidden cost of ignoring this systematic approach is wasted effort and a lack of progress. By contrast, embracing gridding and constraints provides a structured pathway to innovation, making the creative process more predictable and less reliant on chance.

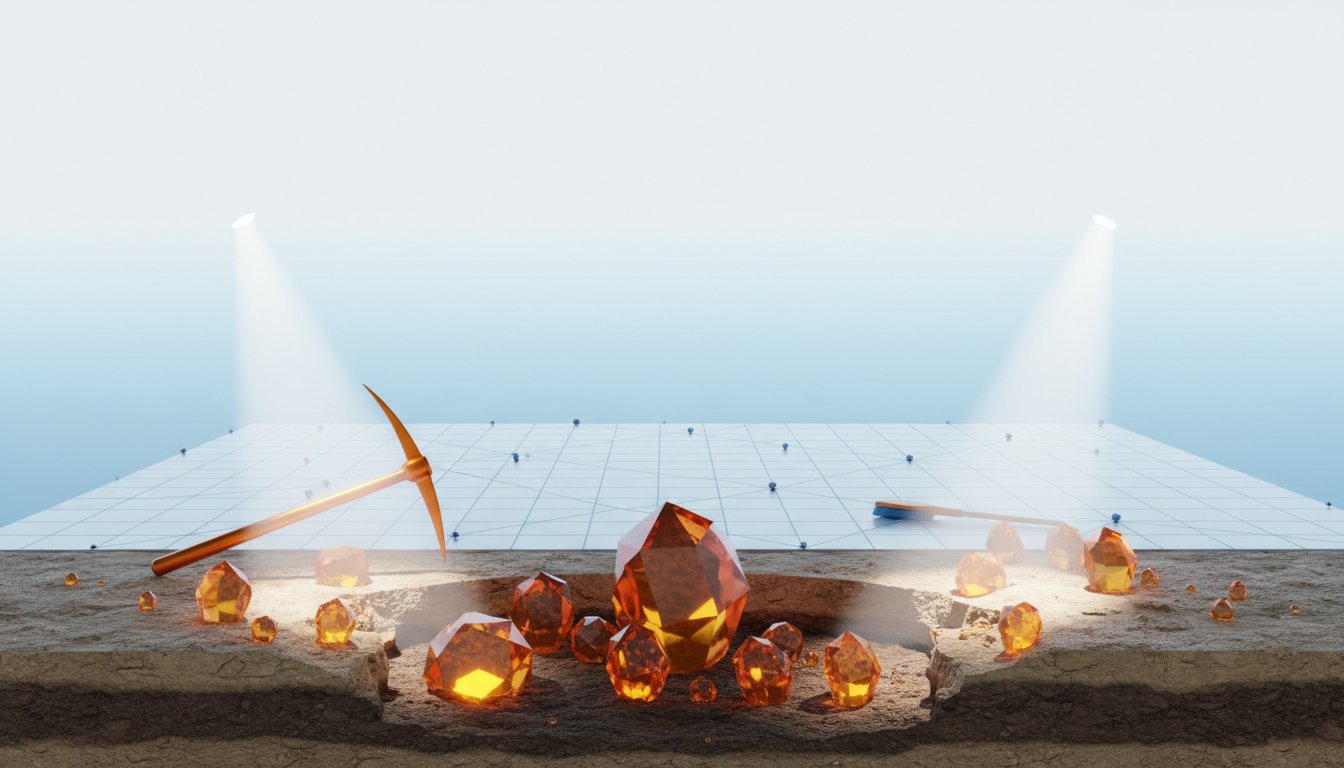

Digging and Sifting: The Rigor of Idea Refinement

The final stages involve "digging" -- generating a high volume of ideas without immediate judgment -- and "sifting" -- critically evaluating and refining those ideas. The "more is more" philosophy in the digging phase, where generating many ideas, even "bad" ones, is encouraged, sets the stage for a robust selection process. The role of AI here is framed as a powerful excavator, capable of clearing a lot of ground quickly, but requiring human direction to ensure novelty and prevent homogenization.

The critical insight in the sifting phase is the need for hard-headed objectivity, which often clashes with our natural biases. The "creative endowment effect," the tendency to overvalue our own ideas simply because we generated them, is a significant hurdle. Newman's research shows that others are often better at identifying the truly valuable ideas within a set. This suggests a downstream consequence: personal attachment to one's own ideas can blind individuals to their flaws and prevent objective evaluation. The advantage of overcoming this bias is the ability to select the strongest ideas, leading to more impactful outcomes.

A crucial aspect of sifting is subtraction. While we are adept at adding to ideas, we often neglect the power of removing elements to improve clarity and effectiveness. The raft metaphor--making an idea watertight by finding and plugging holes--vividly illustrates this. This challenges the conventional wisdom of always building more, suggesting that simplification and refinement through subtraction can be more powerful.

"The notion there is, I want to keep track of everywhere I've searched, where did I find stuff, and importantly, where didn't I find stuff?"

-- Dr. George Newman

The final challenge highlighted is the impact of praise. While seemingly positive, receiving premature praise can stifle further exploration and refinement, as individuals become reluctant to prove the praise wrong. This means actively seeking constructive criticism rather than just validation. The ultimate advantage of rigorous sifting, including subtraction and managing the impact of feedback, is the production of truly robust and valuable ideas, rather than merely a collection of novel but unpolished concepts. This requires significant emotional regulation, as the most promising ideas may initially feel uncomfortable or anxious.

Key Action Items

- Embrace the "Archaeologist" Mindset: Actively search for ideas in the external world through observation, conversation, and exploration. (Immediate Action)

- Engage Socially for Inspiration: Intentionally seek out diverse perspectives and environments; avoid prolonged isolation when seeking new ideas. (Immediate Action)

- Practice the "5% Novelty Rule": Focus on building upon existing ideas with a small, unique twist rather than striving for complete originality. (Ongoing Practice)

- Systematically Grid Your Search: Define a clear guiding question and map out where you are exploring for ideas to ensure thoroughness. (Over the next quarter)

- Actively Seek and Utilize Constraints: Frame limitations as opportunities for innovation; don't shy away from them. (Immediate Action)

- Prioritize Subtraction in Refinement: When evaluating ideas, focus on what can be removed to improve clarity and effectiveness, not just what can be added. (Over the next 1-3 months)

- Seek Constructive Criticism Over Praise: When receiving feedback, actively look for ways to improve and refine, even if it means challenging initial positive reactions. (Ongoing Practice)

- Develop Emotional Regulation for Novelty: Be open to ideas that initially feel uncomfortable or anxious, as these can often be the most promising. (This pays off in 6-12 months as idea quality improves)