Automating iPSC Manufacturing for Scalable, Cost-Effective Cell Therapies

The dream of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) therapies, which promise to regenerate damaged tissues and cure diseases like Parkinson's and leukemia, is currently bottlenecked by an "artisanal" manufacturing process. This labor-intensive, multi-month procedure costs hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient, severely limiting scalability. Nabiha Saklayen, CEO of Cellino, is tackling this by applying physics principles, particularly lasers and automation, to create a highly precise, scalable, and eventually automated iPSC production system. The hidden consequence of the current approach is that even successful iPSC therapies will remain inaccessible to the vast majority of patients due to prohibitive costs and production constraints. This conversation reveals that true progress in regenerative medicine hinges not just on scientific discovery but on solving the complex engineering and manufacturing challenges that enable widespread access. Those who understand and invest in these downstream manufacturing implications, rather than just focusing on initial therapeutic breakthroughs, will gain a significant competitive advantage in bringing these life-changing treatments to millions.

The Hidden Bottleneck: Why Artisanal Stem Cell Production Threatens a Medical Revolution

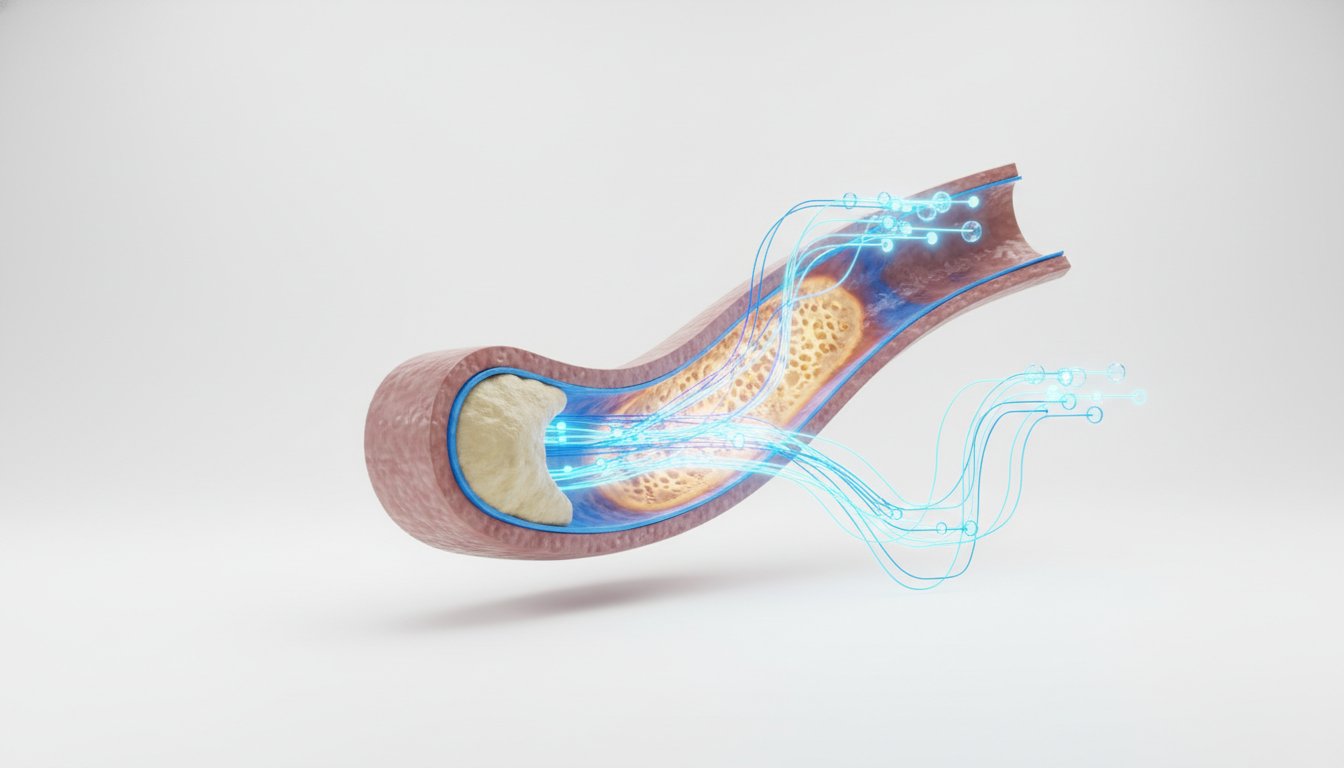

The promise of induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) therapies is nothing short of revolutionary. Imagine a future where a patient's own cells can be coaxed into becoming any cell type needed to repair damaged organs, reverse degenerative diseases, or combat intractable illnesses. This vision, once confined to science fiction, is rapidly approaching reality, with clinical trials underway for conditions ranging from Parkinson's disease to leukemia. Yet, a critical, often overlooked, hurdle stands between this groundbreaking potential and widespread patient access: the manufacturing process itself.

In this conversation with Nabiha Saklayen, co-founder and CEO of Cellino, we uncover a system-level problem that threatens to relegate these life-saving therapies to a luxury for the few, rather than a standard of care for the many. While the scientific breakthroughs in reprogramming adult cells into iPSCs are monumental, the subsequent production of these cells remains stubbornly "artisanal." This means that even as researchers and clinicians achieve therapeutic success in the lab and in early trials, the sheer labor, time, and cost involved in producing iPSCs for each individual patient create a downstream consequence that could cripple the entire field. The obvious answer--that we need more scientists--is insufficient. The deeper issue lies in the fundamental design of the manufacturing process, a system that, if left unaddressed, will ensure that even the most effective iPSC therapies remain out of reach for millions.

The Artisanal Bottleneck: Why the Obvious Fix Makes Things Worse

The journey from a patient's blood sample to a therapeutic dose of iPSC-derived cells is a marvel of modern biology, but it is also a testament to the limitations of current manufacturing paradigms. As Nabiha Saklayen explains, the process of creating iPSCs is still largely a manual endeavor, demanding immense skill, dedication, and time from highly trained scientists.

"You're basically having these brilliant scientists looking under a microscope, holding cells in the dish, and then scraping with a pipetter," Saklayen describes. This "artisanal" approach, characterized by meticulous hand movements and subjective visual assessments--scientists noting "smiley faces" or other subtle cellular features--is not merely inefficient; it is a direct impediment to scaling. These scientists are described as "working 10 hours a day scraping cells, not taking vacations, trying to get to work during the craziest snowstorms because if they don't show up, that run dies." This level of personal reliance and the inherent variability of manual processes create a system rife with potential for error, inconsistency, and, most critically, an insurmountable ceiling on production volume.

The consequence of this artisanal approach is stark: astronomical costs and glacial timelines. Saklayen notes that even with improvements, the cost estimates for iPSC production hover in the "hundreds of thousands of dollars for each patient." The entire manufacturing process can take "three to four months." This reality presents a profound downstream effect: even if a clinical trial proves an iPSC therapy is safe and effective, its commercial viability for millions of patients is immediately jeopardized. The system, as it stands, is designed for research and niche applications, not for mass-market healthcare.

Saklayen powerfully articulates this hidden consequence: "if a team like ours isn't brave enough to try to go after this, this might not be resolved for a few decades." She warns of a future where complex cell and gene therapies navigate the arduous path through Phase 3 approvals, only to falter at the commercial stage because "they're not meeting the patient." This failure stems directly from the inability to produce these therapies at a scale and cost that aligns with the needs of a broad patient population. The immediate problem--creating effective iPSC therapies--is being solved, but the downstream problem--making them accessible--is being systematically ignored by those who don't confront the manufacturing reality.

The Hidden Cost of Speed: Why Shortcuts Lead to Dead Ends

In the high-stakes world of biotechnology, the pressure to demonstrate progress and achieve milestones can be immense. This pressure often leads to a temptation to take shortcuts, to implement solutions that offer immediate gains but fail to account for their long-term systemic impact. Saklayen emphasizes the importance of resisting this temptation, particularly in the context of scaling iPSC manufacturing.

"It's tempting to take shortcuts and, 'Oh, we could do this and this will be much faster,'" she observes. However, the critical question her team constantly asks is, "How will this solution address a million patients annually?" This forward-looking perspective is essential for avoiding what Saklayen calls "kludges"--solutions that are more efficient than current manual methods but remain fundamentally "kludgy and artisanal and not great to scale."

The consequence of prioritizing short-term speed over long-term scalability is the creation of technical debt that compounds over time. A solution that seems efficient today might become an insurmountable barrier to growth tomorrow. For instance, a team might develop a slightly faster manual method for cell selection. While this offers an immediate improvement, it doesn't fundamentally alter the labor-intensive nature of the process. The system still relies on human hands and human eyes, capping the potential patient throughput.

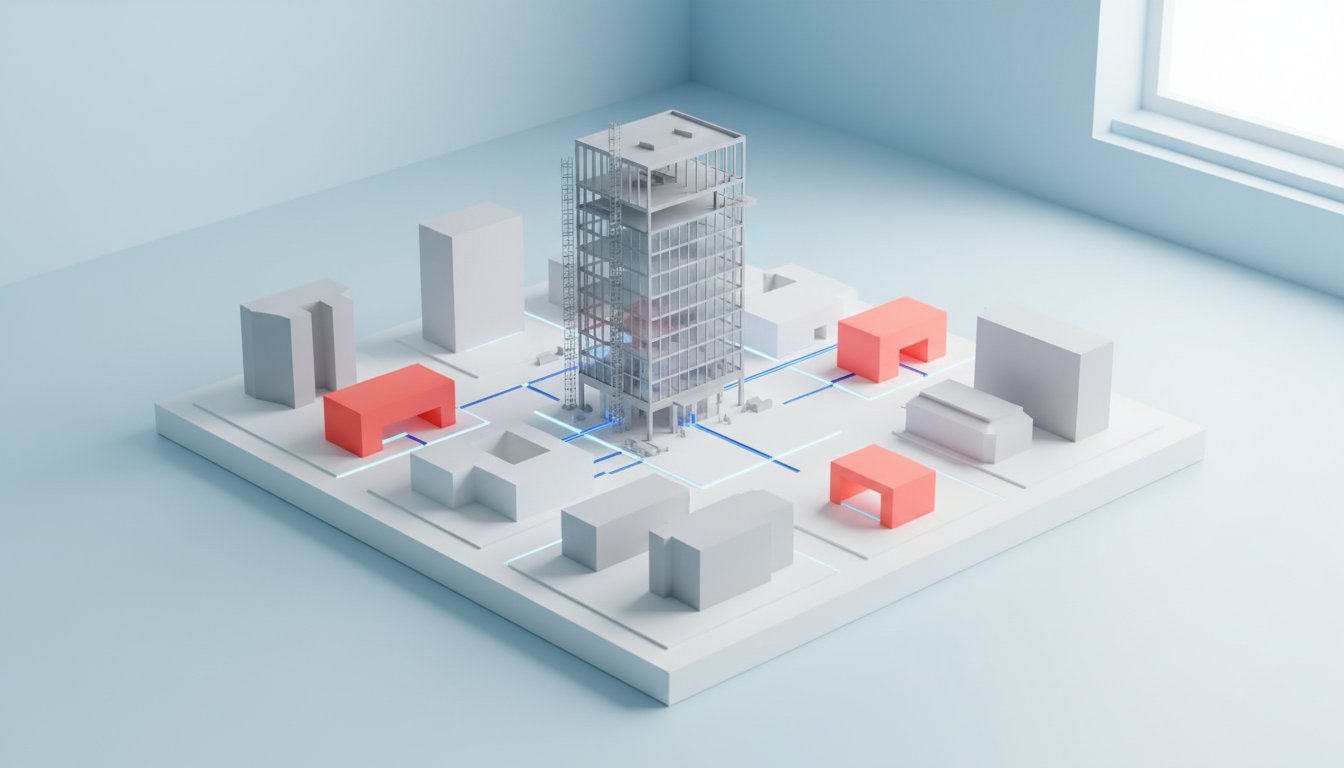

Saklayen's company, Cellino, is actively building a "closed system" called Nebula, which represents a significant departure from these incremental, shortcut-driven approaches. This system aims to encapsulate the entire manufacturing process within automated, iPhone-sized cassettes. This vision directly confronts the hidden cost of speed by investing in a fundamentally different manufacturing architecture. The immediate discomfort--the significant R&D investment and the challenge of developing entirely new automated processes--is undertaken precisely because the alternative, relying on faster but still artisanal methods, leads to a dead end for patient access. The system's response to the pressure for speed, if unchecked, is to create a bottleneck that prevents the very therapies it enables from reaching those who need them.

The 18-Month Payoff Nobody Wants to Wait For: Building for Scale from Day One

The conventional wisdom in drug development often focuses on demonstrating therapeutic efficacy first, with manufacturing scale-up addressed later. However, Saklayen argues for a radical shift in this paradigm: "I do feel very strongly that it's important to push forward trials and build for scale from the get-go." This perspective is rooted in a deep understanding of systems thinking and consequence mapping.

The downstream effect of not building for scale from the outset is a recurring pattern observed in other cell therapies, such as CAR T. Saklayen points out that despite CAR T therapies being a "signal achievement," the maximum number of patients dosed annually has remained around 10,000, a fraction of the potential patient pool. This stagnation, she explains, is due to an "infrastructure problem. It's a scale problem. It's a lack of manufacturing at scale."

Cellino's approach is to tackle the manufacturing challenge concurrently with the scientific and clinical development. Their automated optical bioprocess, powered by lasers and AI, is designed for precision and scalability. The development of their closed system, Nebula, further embodies this principle. By creating iPhone-sized cassettes that function as self-contained clean rooms, they aim to eliminate the need for massive, expensive cleanroom facilities, a significant barrier to distributed manufacturing.

This strategy requires significant upfront investment and a willingness to undertake difficult, long-term projects with delayed payoffs. Saklayen admits, "It was hard for me to come to terms with, given that we had raised a big round, a lot of people were talking about us. But I also felt, I kept telling my team this, 'We have to give it our best shot.'" This commitment to building for scale from the beginning, even when it's the harder, less immediately gratifying path, is where competitive advantage is forged. Most companies, driven by immediate pressures, will not invest the time and resources into building a scalable manufacturing infrastructure early on. This creates an opportunity for those, like Cellino, who are willing to undertake the "18-month payoff nobody wants to wait for," a payoff that ultimately unlocks the true potential of iPSC therapies.

Where Others Won't Go: AI and Laser Precision as the Unpopular Moat

The application of advanced technologies like lasers and artificial intelligence in iPSC manufacturing is not merely an optimization; it is a fundamental re-engineering of a broken system. Saklayen's background in physics and lasers provided the initial insight into how precision tools could be applied to biological processes, moving beyond the limitations of human dexterity.

"You have a whole range of how good our scientists are globally," Saklayen notes, highlighting the inherent variability in manual cell selection. This subjectivity is precisely what AI and machine learning aim to overcome. By feeding vast amounts of imaging data into algorithms, Cellino can train models to identify optimal cells with a consistency and speed that far surpasses human capability. "If humans can see something by eye, we're probably able to train an algorithm to do that," Saklayen states, emphasizing the power of pattern recognition at scale.

The use of "time series data" is particularly crucial. By analyzing the evolution of cell colonies over time--akin to a time-lapse video--AI can predict future outcomes, identifying potentially problematic cells or colonies early in the process. This predictive power is a significant advantage, allowing for the elimination of suboptimal cells before months of work are invested, thereby reducing waste and increasing yield. This capability is what Saklayen likens to "looking in the crystal ball" for cell manufacturing.

This reliance on sophisticated technology, coupled with a rigorous approach to data generation and validation, creates a moat that is difficult for competitors to replicate. The upfront investment in developing these AI models, acquiring precise laser-based tools, and integrating them into a closed, automated system is substantial. Furthermore, this approach requires a different kind of expertise--a blend of physics, engineering, biology, and data science--that is not readily available.

The "unpopular" aspect of this strategy lies in its complexity and the extended timeline for realizing its full benefits. While other companies might focus on incremental improvements to manual processes, Cellino is building a fundamentally new manufacturing paradigm. This requires patience and a long-term vision, qualities that are often at odds with the rapid-return expectations of the venture capital world. However, it is precisely this willingness to invest in difficult, cutting-edge solutions--where "others won't go"--that positions Cellino to solve the critical scaling problem and make iPSC therapies a reality for millions.

The System Responds: Navigating Regulatory Landscapes and Future Visions

The path to commercializing novel therapies is rarely straightforward, and iPSC therapies face unique challenges, particularly concerning manufacturing and regulatory approval. Saklayen's proactive engagement with the FDA is a critical component of her strategy to build a scalable system.

"The last 10 years of cell and gene therapies have been transformative in terms of curative medicines, but everybody is missing the impact of scale, including the regulators," Saklayen observes. She highlights the FDA's surprisingly "technology-forward" stance, noting their engagement with AI teams and their willingness to explore new manufacturing paradigms. This collaborative approach, where Cellino is "working with the FDA, and we're going to present data, and we're going to work with our clinical collaborators," is essential for de-risking the regulatory pathway for their novel automated system.

The system's response to Cellino's innovative approach is not limited to regulatory bodies. It also involves how clinical collaborators and patients will interact with this new technology. The vision is for machines, roughly the size of "one or two refrigerators," to be deployed, capable of producing personalized therapies. The "artisanal knowledge and the clean room and everything is in the machine," embedded within intelligent systems. This shifts the locus of manufacturing from specialized clean rooms to more accessible, automated platforms, potentially even within or near hospitals.

Looking ahead, Saklayen paints a compelling picture of the future. In five years, she anticipates significant changes for Parkinson's patients, with iPSC therapies becoming a viable treatment option. In ten years, she foresees at least five more diseases benefiting from allogeneic (off-the-shelf) therapies, and autologous (patient-specific) trials reaching Phase 3 in a scalable manner. This future is contingent on solving the manufacturing puzzle.

The ultimate goal is to move beyond merely treating symptoms to reversing disease and achieving curative medicines. This requires a paradigm shift, driven by the passion to address aging, loss, and the desire to keep people healthier for longer. Saklayen's optimism, fueled by the collective willpower of scientists and the potential for human regeneration, underscores the long-term vision. The system, in this context, is not just the biological or manufacturing process, but the entire healthcare ecosystem, which must adapt to embrace these transformative regenerative therapies. By building for scale and working collaboratively with regulators and clinicians, Cellino aims to ensure that the system's response to these advancements is one of widespread access and profound patient benefit.

Key Action Items

- Invest in foundational manufacturing R&D from Day One: Do not treat manufacturing scale-up as an afterthought. Integrate it into the earliest stages of therapeutic development, as Cellino is doing with its automated optical bioprocess and Nebula system. This requires a commitment to building scalable infrastructure even before clinical validation. This pays off in 3-5 years and beyond.

- Embrace automation and AI for precision and consistency: Identify manual, subjective processes in your workflow and explore how AI and advanced automation can replace them. This is crucial for achieving the reproducibility and scale needed for widespread adoption. Immediate action: Pilot AI for pattern recognition in data analysis; Longer-term investment: Develop integrated automated workflows.

- Proactively engage with regulators on advanced manufacturing technologies: Do not wait for regulatory approval to become a roadblock. Initiate dialogue early, present data on novel manufacturing processes, and collaborate to define new standards, as Cellino has done with the FDA. This requires ongoing effort, with initial engagement within the next quarter.

- Prioritize durability and long-term viability over immediate speed: Resist the temptation to implement "kludgy" solutions that offer short-term efficiency gains but cap future growth. Focus on building systems that can genuinely scale to meet demand, even if this means a longer development timeline. This is a continuous strategic choice, with immediate implications for project prioritization.

- Develop expertise at the intersection of physics, biology, and data science: The complex challenges of advanced therapies require interdisciplinary teams. Invest in hiring and training individuals who can bridge these fields, enabling innovative solutions that leverage precision engineering and computational power. This is a 12-18 month hiring and team-building strategy.

- Foster a culture of long-term vision and optimism: Tackling monumental problems like scaling iPSC therapies requires sustained effort and belief in the mission. Encourage your team to focus on the ultimate patient impact and the systemic changes required to achieve it, even when faced with immediate challenges or market downturns. This is an ongoing cultural imperative.

- Build closed, modular systems for manufacturing: Explore the creation of self-contained manufacturing units that minimize external dependencies and contamination risks. This approach, exemplified by Cellino's Nebula cassettes, can democratize access to advanced manufacturing capabilities. This is a 2-3 year development horizon.