Roman Self-Healing Concrete and Space-Based Data Centers

In this conversation, Dr. Ad Mir Mashich and Dr. Benjamin Lee reveal that seemingly straightforward technological advancements often hide complex, long-term consequences. The Roman concrete's self-healing properties, achieved through a difficult "hot mixing" process, offer a durable, albeit initially uncomfortable, solution that modern concrete lacks. Similarly, the allure of abundant solar power for space-based data centers overlooks immense challenges in launch costs, debris risk, cooling, and data transfer, suggesting that focusing on terrestrial efficiency and specialized models might yield more immediate and sustainable advantages. This discussion is crucial for engineers, technologists, and policymakers who must navigate the trade-offs between immediate problem-solving and building resilient, long-term infrastructure. Understanding these hidden dynamics provides a significant advantage in anticipating future challenges and designing more robust solutions.

The Unseen Consequences of Innovation: Roman Concrete and Orbital Data Centers

In the relentless pursuit of progress, we often celebrate the immediate solutions to pressing problems. Yet, as a recent conversation on Science Friday revealed, the most impactful innovations are rarely the most obvious. Dr. Ad Mir Mashich's exploration of ancient Roman concrete and Dr. Benjamin Lee's analysis of space-based data centers both highlight a critical blind spot in our collective thinking: the tendency to overlook the downstream effects of our decisions. While the Romans may have stumbled upon a self-healing concrete through a process that was initially more challenging, and the allure of limitless solar power in space beckons, the true value lies not in the immediate fix, but in the durable advantage forged through understanding and embracing complexity. This conversation serves as a stark reminder that the path to true advancement is often paved with immediate discomfort, leading to lasting resilience, a lesson that conventional wisdom frequently fails to grasp.

Why the Obvious Fix Makes Things Worse: The Roman Concrete Revelation

The durability of Roman structures like the Pantheon and its aqueducts has long been a source of wonder. For millennia, these marvels have stood as testaments to ancient engineering, a stark contrast to the often-limited lifespan of modern concrete. The key, it turns out, lies in a subtle but profound difference in how their cement was made. While ancient scholars like Vitruvius documented a process involving slaked lime mixed with volcanic ash, a groundbreaking discovery at a Pompeii construction site, preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, has unveiled a different, more potent method.

Dr. Ad Mir Mashich, an associate professor at MIT, co-authored the study that unearthed this secret. He describes the scene as stepping into a frozen moment in time, an active construction site halted mid-action by the volcanic ash. This excavation provided an unprecedented glimpse into the raw materials and their preparation. The critical insight? Instead of the documented process of slaking lime first, the ancient Pompeians appear to have engaged in "hot mixing"--pre-mixing calcined stone (quicklime) and volcanic ash dry, then adding water.

This seemingly minor procedural shift has profound implications. The reaction between quicklime and water generates significant heat, reaching temperatures up to 200 degrees Celsius in hotspots. This "hot mixing" process, though potentially more complex and requiring immediate handling due to the heat, is the very reason for the concrete's extraordinary longevity. As Dr. Mashich explains, this method results in a "self-healing concrete." When micro-cracks form, the residual quicklime within the mix can react with water and carbon dioxide, dissolving and recrystallizing to fill these cracks. This inherent repair mechanism is absent in most modern concrete, which is designed for rapid setting and ease of use, often at the expense of long-term resilience.

The conventional approach to concrete production prioritizes immediate efficiency and predictable outcomes. The documented "Vitruvian" method, which involves slaking lime first, offers a more controlled and less intensely exothermic reaction. However, this process sacrifices the self-healing capability. The discovery in Pompeii suggests that the Romans, through empirical observation or perhaps a more intuitive understanding of material properties, embraced a method that demanded more immediate effort and attention--the heat and reactivity of hot mixing--but yielded a material that repaired itself over centuries. This is a classic example of how prioritizing immediate ease can lead to downstream degradation, while embracing a more difficult, upfront process can create lasting advantage. The challenge for modern engineering, as Dr. Mashich and his team are pursuing, is to reintroduce this self-healing property into contemporary concrete, a testament to the enduring lessons hidden within ancient practices.

The Allure of the Infinite: Data Centers in Space

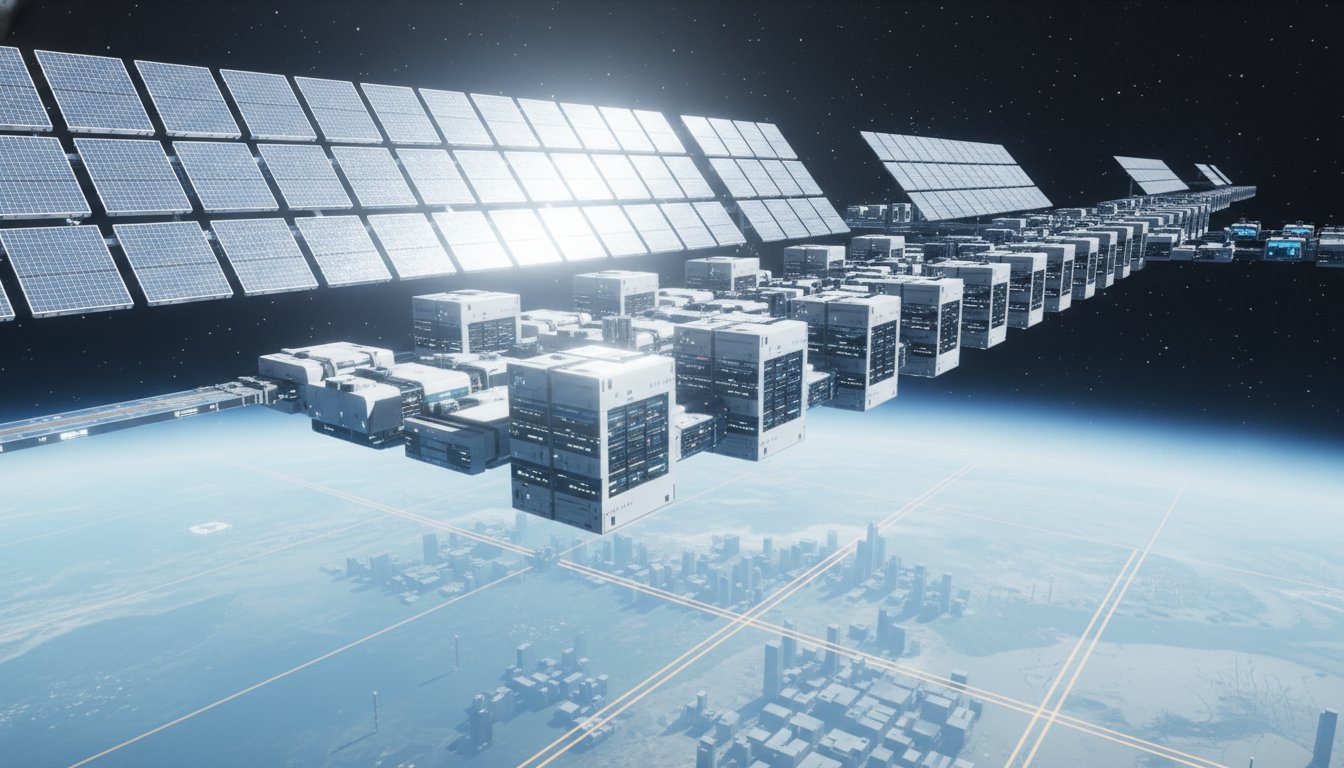

Shifting from the ancient to the futuristic, the conversation then turned to the immense power demands of modern computing, particularly for artificial intelligence. As AI models grow more sophisticated, so does their appetite for energy. This has led some of the most prominent figures in tech, including Sundar Pichai of Google, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, and Sam Altman of OpenAI, to consider a radical solution: moving data centers into space. The primary driver is the prospect of abundant, uninterrupted solar power.

Dr. Benjamin Lee, a professor of electrical and systems engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, brings a systems-thinking perspective to this ambitious vision. He confirms that energy scarcity on Earth's grids is a significant bottleneck for hyperscale data centers, which can consume hundreds of megawatts. The intermittency of solar power on Earth--the inability to compute during the night--further fuels the appeal of space, where sun-synchronous orbits could provide near-continuous solar exposure.

However, Dr. Lee immediately injects a dose of realism, emphasizing that "the devil is in the details." The sheer scale of the undertaking is staggering. To power gigawatt-scale data centers, kilometers of solar panels would be required. The cost and logistical challenge of launching such massive structures into orbit are immense. Beyond the initial deployment, the harsh environment of space presents formidable obstacles.

The Cascading Challenges of Orbital Infrastructure

The immediate appeal of 24/7 solar power quickly encounters a series of compounding problems that highlight the limitations of a purely "obvious solution" approach.

- The Launch Cost Barrier: The sheer weight of gigawatt-scale solar arrays and the associated data center hardware translates into astronomical launch costs. This immediate financial hurdle is a significant deterrent, suggesting that the upfront investment would dwarf any potential energy savings for a considerable period.

- Space Debris and Reliability: As Dr. Lee points out, anything deployed in space, especially on such a grand scale, faces the constant threat of space debris. The reliability and repair of components become critical challenges. Unlike terrestrial data centers where maintenance crews can readily access and replace hardware, orbital repairs are exponentially more complex and costly, if even feasible for massive structures. This introduces a long-term risk of catastrophic failure that is difficult to mitigate.

- The Cooling Conundrum: On Earth, data centers rely heavily on water or air for cooling. Space, while cold, lacks an atmosphere to facilitate convective cooling. The solution would involve radiative cooling, which, as Dr. Lee explains, requires even larger surface areas--more panels--to radiate heat into the vacuum of space. This exacerbates the problem of scale and complexity, adding another layer of engineering difficulty and cost that is not immediately apparent when envisioning a "solar-powered" data center.

- The Data Transfer Bottleneck: Even if power and cooling are somehow managed, the movement of data presents a fundamental challenge. While radio frequencies can support up to 10 gigabits per second, training large AI models requires massive datasets. Transporting petabytes of data from Earth to an orbital data center, or vice versa, would be incredibly slow and inefficient. Dr. Lee draws a poignant analogy: sending a disk in the mail might be faster than transmitting large volumes of data to space. This highlights how a solution optimized for one aspect (power) can create a severe bottleneck in another essential function (data transfer), rendering the entire system less effective.

The Temptation of the Quick Fix vs. The Power of Specialization

Dr. Lee articulates a crucial point about current AI development: the pursuit of general-purpose models capable of answering any query is computationally expensive. This "brute force" approach, where immense computational power is applied to achieve broad capabilities, is a prime example of prioritizing immediate functionality over long-term efficiency. The alternative, he suggests, is to develop specialized models for specific domains like finance, medicine, or education. These models, while less versatile, could achieve comparable results with significantly less computational power and energy.

The reason this specialized approach hasn't been widely adopted, Dr. Lee implies, is a lack of clarity on which applications will truly revolutionize society. The drive to build models that can handle "any possible query" is a hedge against missing out on unforeseen breakthroughs. However, this generality comes at a substantial energy cost. The allure of building ever-more-capable, general AI models often overshadows the more difficult, but potentially more sustainable, path of developing specialized, efficient models. This mirrors the Roman concrete example: the "obvious" path of modern concrete prioritizes ease of production, while the "difficult" path of hot mixing offers self-healing durability.

The Long Horizon: When Will Space Data Centers Become Reality?

Both Dr. Mashich and Dr. Lee agree that orbital data centers are not a near-term solution. Dr. Lee suggests that within the next 10-15 years, advancements in terrestrial energy infrastructure--battery capacity, solar deployment, and potentially small modular reactors--could significantly alter the energy landscape, potentially diminishing the perceived need for space-based solutions.

However, the conversation doesn't dismiss the idea entirely. Dr. Lee sees potential for "more compute in space" as a natural progression. As private companies like SpaceX continue to drive down launch costs and constellations of communication satellites become more prevalent, integrating some level of compute power alongside communication infrastructure makes sense. This could involve processing data collected by satellites directly in orbit, rather than transmitting it all back to Earth. This represents a more nuanced application of orbital computing, focused on specific advantages rather than a wholesale replacement of terrestrial infrastructure.

The advantage here lies in recognizing that "solved" problems are not always "actually improved" problems. Modern concrete is "solved" in the sense that it can be produced efficiently, but it is not "actually improved" in terms of its lifespan and resilience compared to its ancient Roman counterpart. Similarly, while we can imagine data centers in space, the immediate terrestrial challenges of energy efficiency and specialized AI models might offer more tangible and sustainable improvements in the shorter term. The ambitious vision of space-based data centers, while compelling, requires a deep understanding of the cascading consequences that extend far beyond the immediate benefit of abundant solar power.

Key Action Items

- Prioritize "Hot Mixing" Analogues for Durability: Investigate and pilot processes that involve upfront material complexity or heat generation, mirroring the Roman "hot mixing" technique, to imbue modern materials with self-healing or enhanced durability properties. This offers a 12-18 month payoff in material resilience, though initial implementation may require significant R&D and process adjustment.

- Develop Specialized AI Models: Shift focus from building monolithic, general-purpose AI models to creating domain-specific models for finance, medicine, education, etc., that achieve comparable results with significantly lower computational and energy costs. This requires immediate strategic planning and R&D investment, with efficiency gains realized over the next 1-3 years.

- Explore Hybrid Orbital Compute Solutions: Instead of full data center replacement, focus on integrating modest compute capabilities into existing or planned satellite constellations for localized data processing, particularly for sensor data collected in orbit. This is a medium-term opportunity, with potential pilot projects within 3-5 years, leveraging decreasing launch costs.

- Quantify Downstream Energy Costs of AI: Implement rigorous lifecycle assessments for AI model development and deployment, explicitly accounting for the energy consumption of training, inference, and ongoing maintenance, to reveal the true cost beyond immediate computational output. Immediate action required; this analysis will inform long-term strategy and investment over the next quarter.

- Invest in Advanced Terrestrial Cooling Technologies: Continue research and development into highly efficient terrestrial data center cooling systems, including advanced liquid cooling and waste heat recapture, to mitigate the energy demands that drive the search for space-based solutions. This is an ongoing investment with immediate R&D and potential deployment over 1-2 years.

- Conduct Space Debris Mitigation and Repair Strategy Research: For any future orbital infrastructure, dedicate significant resources to developing robust strategies for debris avoidance, component repair, and end-of-life decommissioning to address the long-term reliability challenges. This is a foundational, long-term research effort, with initial strategy development over the next 6-12 months.

- Embrace "Unpopular but Durable" Solutions: Foster organizational cultures that value and reward the adoption of solutions that may be more difficult or less immediately gratifying to implement but offer significantly greater long-term resilience and competitive advantage. This requires a cultural shift, with initial impacts observable within 6-18 months.