TLDR: Building a successful product isn't just about creating a minimum viable product (MVP), but a "minimum evolvable product" (MEP) capable of adapting to early users. The hidden consequence of focusing solely on MVP is missing the crucial feedback loop that shapes a product's true market fit and evolutionary path. This conversation reveals that finding the first customers is a search for individuals with a burning need or a love for early adoption, not a persuasion challenge. Those who understand this can gain a significant advantage by embracing experimentation, charging real money early for sharper feedback, and closely studying their initial user base. This insight is critical for founders, product managers, and anyone aiming to navigate the uncertain waters of product development, offering a strategic edge by focusing on evolution rather than premature perfection.

Introduction:

The conventional wisdom for startups is to build a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Yet, this mantra often leads founders astray, focusing them on a static endpoint rather than the dynamic journey of product creation. What if the most critical element isn't just viability, but evolvability? In this conversation, Ankit Gupta of Y Combinator introduces the concept of the "Minimum Evolvable Product" (MEP), arguing that the true path to product-market fit lies not in perfecting an initial offering, but in building something that can actively adapt and evolve based on the pressures and feedback of its earliest users. The obvious answer--build something that works--is insufficient because it ignores the profound impact of those first few users. They are not just customers; they are co-creators, shaping the very market the product will inhabit. This framing reveals deeper system dynamics at play: the product's evolution is path-dependent, influenced by the unique needs and desires of those willing to take a chance on the nascent and imperfect.

The Search for the First Believers: Why Persuasion Fails Where Discovery Succeeds

The journey to acquiring a product's first customers is often misunderstood. Many founders believe they need to persuade hesitant individuals to adopt their new creation. However, as Ankit Gupta explains, this is fundamentally a search problem, not a persuasion problem. The critical insight here is that most people are not early adopters. The vast majority of consumers today adopted their favorite products long after they were established, not when they were experimental and unproven. This means the pool of potential early customers is a select group. Gupta highlights two key archetypes within this group: those with a "burning issue" that a new product might solve, and individuals who simply "love trying out products from startups."

The implication of framing this as a search is profound. Instead of crafting elaborate pitches, founders should focus on identifying and reaching these specific individuals. Gupta illustrates this with a personal anecdote: his team needed an inference API quickly and found a startup willing to provide it, becoming their first customer. The startup's size or reputation was irrelevant; their ability to solve a pressing problem was paramount. This underscores that early adopters are motivated by utility and problem-solving, not by the vendor's established credibility. The hidden consequence of a persuasion-first mindset is wasted effort on individuals who are inherently risk-averse or simply not in the market for nascent solutions. By reframing it as a search, founders can direct their energy more effectively towards those predisposed to engage.

The Power of Paid Feedback: Why Free Users Offer a Distorted View

A counterintuitive rule for acquiring early users, according to Gupta, is to "charge real money early." This advice flies in the face of common startup advice that often suggests offering free trials or freemium models to gain initial traction. However, the reasoning behind charging early is rooted in the quality of feedback. Gupta argues that early adopters and those with a burning problem are rarely price-sensitive. Their primary motivation is to solve their issue, and they are willing to pay for a solution, even an imperfect one.

The immediate benefit of charging is that it filters for users who are serious about the product's value proposition. Paying customers provide sharper, more honest feedback than free users. The downstream effect of this is a more accurate understanding of the product's true market value and the specific pain points it addresses. A customer who has paid a significant amount is more likely to articulate their frustrations and desires clearly, even if they are angry. This heightened level of engagement is invaluable for a nascent product that needs to iterate rapidly. The hidden cost of offering free services is the dilution of feedback; free users may churn without consequence, offer superficial comments, or simply not engage deeply enough to reveal critical flaws or opportunities. By demanding payment, founders receive feedback that is directly correlated with perceived value, guiding the product's evolution with greater precision. This immediate discomfort of asking for money, Gupta suggests, yields a lasting advantage by ensuring the product is built on a foundation of genuine market demand.

Targeted Outreach: The Unseen Channels to Early Adopters

The methods for finding these crucial early users are often unconventional and highly personalized. Gupta emphasizes the importance of "targeted, personal outreach," contrasting it with broad, traditional marketing tactics. A billboard, for instance, is unlikely to reach the specific individuals who are most likely to become a startup's first customers. Instead, the effective channels are those that allow for direct, one-to-one engagement, such as targeted cold emails or even knocking on doors.

This approach has significant downstream effects. Personal outreach allows founders to have direct conversations, understand individual needs, and build relationships. This is critical because early users are not just transactional customers; they are partners in product development. The feedback loop is tighter, and the ability to address specific concerns becomes paramount. The system responds to this personal touch by fostering loyalty and providing more actionable insights. The hidden consequence of relying on mass marketing is that it fails to identify and engage the niche group of early adopters. These individuals often operate in specific communities or networks, and generic advertising will simply not resonate. By investing time in personalized outreach, founders can tap into these networks and connect with the "Gustavs and Ankas" who are actively seeking out new solutions. This requires patience and effort--a discomfort that most companies shy away from--but it creates a durable advantage by building a user base that is intrinsically aligned with the product's mission.

The anthropologist's Gaze: Studying Early Users as a Foundation for Evolution

Once early users are acquired, the next critical step is to "study your early users closely." Gupta likens this to an anthropologist discovering a hidden civilization. This deep dive into user behavior and motivations is not merely about collecting data; it's about understanding the underlying psychology and decision-making processes that led them to embrace an unproven product. Why did they trust you? What unmet needs are they trying to fulfill? How do they make decisions?

This anthropological approach has profound implications for product evolution. By understanding the "why" behind user adoption, founders can identify emerging patterns and anticipate future needs. This allows them to steer the product's development in a direction that resonates deeply with its core audience, rather than guessing at market demands. The system responds to this deep understanding by creating a product that feels intuitively right for its users. The downstream effect is a more robust and adaptable product that can morph into what the market truly desires. The hidden cost of neglecting this deep study is building a product based on assumptions rather than insights. This can lead to features that miss the mark, onboarding processes that alienate users, and ultimately, a product that fails to gain significant traction. The effort required to conduct this deep user study is significant--it demands time, empathy, and a willingness to be surprised--but it lays the groundwork for a product that can genuinely evolve and capture a market.

Embracing Churn: The Engine of Rapid Iteration and Market Discovery

Experimentation is at the heart of building an evolvable product, and Gupta advises founders to "experiment fast and don't fear churn." This means running constant tests on pricing, landing pages, onboarding flows, and features. Simultaneously, founders should strive to make their early users love the product. However, the crucial element is not to panic when users inevitably churn. If a user is annoyed, the personal relationship often allows for a fix. If they leave, it's an opportunity to learn without significant public backlash.

The immediate benefit of this approach is rapid learning. By iterating quickly and accepting that not every user will stick around, startups can efficiently discover what works and what doesn't. The downstream effect is a product that is constantly being refined based on real-world feedback. This iterative process allows the product to adapt to market pressures and evolve more effectively than a product built on rigid initial plans. The system responds to this rapid experimentation by quickly identifying the most viable product directions. The hidden consequence of fearing churn and avoiding experimentation is stagnation. Big companies, for example, cannot afford to run "bad experiments" without significant reputational risk, whereas startups can fail fast and learn faster. This freedom from public scrutiny is a significant competitive advantage. By embracing churn as a natural part of the learning process, founders can accelerate their product's evolution, ensuring it becomes truly aligned with market needs over time, a payoff that takes considerable patience and a willingness to accept temporary setbacks.

The AI Era and the Business of Software: Consumer vs. Enterprise Value

The economic landscape for software, particularly in the age of AI, presents a stark contrast between consumer and enterprise markets. Gupta points out that while personal software spending is relatively low (around $150 per month for an individual), corporate spending on software tools can be orders of magnitude higher, with individual tools costing more than the average personal budget. This gap has significant implications for AI-powered products.

The immediate challenge for consumer-facing AI apps is that advertising revenue often fails to cover the high computational costs of AI models. Consequently, subscription prices must fit within already constrained personal budgets. This economic reality makes it difficult for many consumer AI companies to achieve profitability. The downstream effect is that many AI founders are choosing to target prosumers or businesses, where the perceived value and willingness to pay are significantly higher. Alternatively, they target niche professional users, like doctors, who have high advertising value associated with their user base. The system responds to these economic pressures by shifting the focus of innovation towards markets with greater financial capacity. The hidden consequence of ignoring these economic realities is building a product that is unsustainable in the long run, especially as AI costs continue to rise. This insight highlights a strategic decision point for founders: understanding where the true economic value lies in the current technological landscape can dictate the entire trajectory of product development and market entry, creating a durable advantage for those who target higher-value segments.

Path Dependency: How Early Adopters Sculpt the Future Product

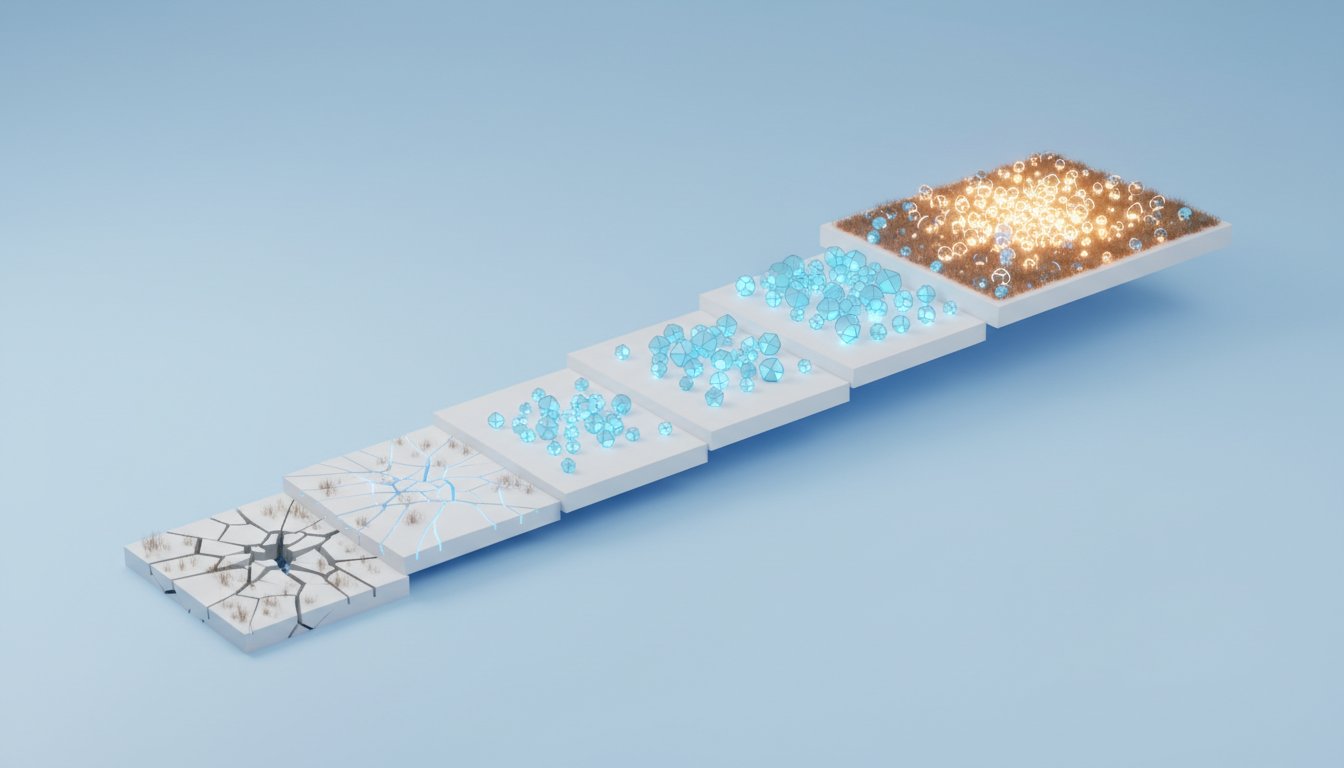

The most profound aspect of early users is their role in shaping the product's evolutionary path. Gupta uses the analogy of a phylogenetic tree, where a startup begins as a simple "amoeba" and, through evolutionary search, can become a complex organism. The key is that this evolution is "path-dependent," meaning the choices made and the pressures encountered early on dictate the future directions the product can take.

The Tesla case study powerfully illustrates this. The Roadster, an expensive and impractical vehicle, served not only as a high-margin product to fund future development but, more importantly, as a search mechanism for early adopters. These were individuals willing to pay a premium for cutting-edge technology and performance, even at the expense of practicality. The downstream effect is evident in Tesla's subsequent mass-market vehicles. The Model Y, for instance, boasts supercar-like acceleration and advanced tech, but its suspension and comfort are less refined than a Toyota. Gupta posits that this is a direct outcome of the early adopters' preferences. If Tesla's initial customers had prioritized comfort and practicality over raw performance, the company's product line would look vastly different today. The immediate benefit for Tesla was securing funding and learning about the market. The lasting advantage came from the evolutionary path forged by those early adopters, shaping the company's DNA. The hidden consequence of not understanding this path dependency is building a product that, while viable, may never evolve into something truly market-defining because its initial user base did not represent the future direction. Founders who embrace the MEP philosophy, understanding that their early users are not just customers but architects of the future, can build products with a more robust and compelling evolutionary trajectory, a strategy that requires patience and a willingness to let the market guide the hand of innovation.

Key Action Items:

- Shift from MVP to MEP: Reframe your product development goal from simply creating a "minimum viable product" to a "minimum evolvable product." This means focusing on building a core that can adapt and respond to user feedback, rather than aiming for initial perfection. (Immediate action)

- Embrace the Search for Early Adopters: Recognize that acquiring your first customers is a search for individuals with a burning problem or a passion for new technology, not a persuasion challenge. Invest time in identifying and reaching these specific user archetypes. (Over the next quarter)

- Charge for Your Product Early: Implement a pricing strategy from the outset. This filters for serious users and provides sharper, more valuable feedback than free offerings. The discomfort of asking for payment now will yield more accurate market insights later. (Immediate action)

- Conduct Deep User Anthropology: Treat your early users as subjects of study. Dedicate time to understanding their motivations, decision-making processes, and the "why" behind their adoption. This insight is crucial for guiding product evolution. (Ongoing, with initial deep dives over the next 2-3 months)

- Experiment Relentlessly and Accept Churn: Run continuous experiments on pricing, features, and onboarding. Do not fear user churn; view it as a natural part of the learning process that provides valuable data for iteration. (Immediate and ongoing)

- Target Higher-Value Markets (Especially in AI): Given the economic realities of AI development, consider focusing on prosumers or businesses that can afford higher price points and offer more substantial ROI, rather than solely relying on the constrained consumer market. (Strategic consideration for the next 6-12 months)

- Understand Path Dependency: Acknowledge that your early product decisions and user base will fundamentally shape your product's future trajectory. Build with an awareness that the early evolutionary steps will dictate later possibilities, creating a unique and durable competitive advantage. (Long-term strategic mindset, paying dividends in 12-18 months and beyond)