Experimentation Drives Scientific Discovery and Societal Benefit

The universe is far stranger and more magnificent than we can easily grasp, a truth Dr. Suzie Sheehy masterfully unpacks in The Matter of Everything. This isn't just a book about physics; it's a chronicle of human curiosity expressed through groundbreaking experiments. The hidden consequence of this exploration is a profound re-evaluation of what "knowing" truly means, revealing that our current understanding accounts for a mere 5% of the cosmos. Readers, particularly those in science, technology, and even the arts, will gain a powerful perspective on how persistent inquiry, even when it aims to disprove, ultimately builds the edifice of knowledge. This conversation offers an advantage by demystifying complex scientific journeys and highlighting the often-unseen ripple effects of experimental breakthroughs, providing a framework for understanding both the universe and the creative process itself.

The Invisible Repulsion: How We Don't Actually Touch Anything

The fundamental nature of reality, as explored by Dr. Suzie Sheehy, reveals that our most basic physical interactions are governed by forces we cannot see. When we perceive ourselves as touching an object -- a chair, the ground, even another person -- we are experiencing the electromagnetic repulsion between the electrons of our own atoms and those of the object. This invisible force field is what prevents physical contact, creating the sensation of solidity and presence. This insight challenges our intuitive understanding of the world, suggesting that the universe operates on principles far removed from our everyday sensory experience. The implications are vast: our perceived reality is a sophisticated illusion woven by fundamental forces, and our direct experience is a testament to the power of electromagnetic fields rather than physical contact.

"The particles in your body are not actually physically touching the particles of the seat or the ground beneath you. It's actually the electrons around the outside of the atoms in your body that are electrically repelling the electrons in the atoms of the chair or the ground and the electromagnetic force is what is holding you apart from those two things."

-- Dr. Suzie Sheehy

This understanding of electromagnetic forces extends beyond mere sensation. It underpins the very structure of matter and the interactions between particles. The experiments Sheehy details in her book, from the discovery of the electron to the exploration of dark matter, are all attempts to probe these fundamental forces and particles. The consequence of such detailed investigation is not just an accumulation of facts, but a gradual unveiling of the universe's intricate architecture. What appears simple on the surface -- sitting in a chair -- is, in reality, a complex interplay of forces that, if fully understood, can lead to innovations in fields like medical treatment, where precise control over particle beams is paramount.

The Unseen Universe: Dark Matter and the Limits of Our Knowledge

One of the most striking revelations from the conversation is the sheer scale of our cosmic ignorance. Despite over a century of intense research in particle physics, the theories and experiments we have meticulously developed only describe about 4-5% of the universe's mass and energy. The remaining 95% is composed of dark matter (approximately 25%) and dark energy (approximately 70-75%), entities we know exist through their gravitational effects but cannot directly detect or comprehend. This vast unknown presents a profound challenge and an immense opportunity for scientific discovery.

The indirect evidence for dark matter, derived from galactic rotation rates and cosmic structure formation, suggests its presence but leaves its nature a mystery. Experiments designed to detect dark matter particles directly, by observing rare collisions with ordinary matter, have yielded tantalizing hints but no definitive proof. The potential discovery of dark matter, especially if confirmed by an experiment in the Southern Hemisphere--like the one being built in Australia to verify an observed annual variation--would be a monumental achievement, fundamentally altering our understanding of the cosmos. The consequence of this cosmic mystery is that the frontiers of physics are not closing; they are expanding, pushing us to develop entirely new theoretical frameworks and experimental technologies.

"People think physics is done and it's only we only know 5% of what's out there... a large proportion of that probably 25% is something called dark matter... it doesn't seem dark matter is not detected in any other way with say light or any other ways that we normally detect things so that's why we call it dark."

-- Dr. Suzie Sheehy

This vast unknown highlights a critical systemic dynamic: scientific progress is not a linear march towards complete knowledge, but an iterative process of discovery, refinement, and the revelation of new questions. The pursuit of understanding dark matter requires pushing the boundaries of experimental design, leading to advancements in detector technology and data analysis. These advancements, in turn, can have unforeseen applications in other fields, demonstrating a fundamental interconnectedness within scientific endeavor. The delayed payoff of understanding dark matter is immense, promising a revolution in our cosmological models and potentially revealing new fundamental forces or particles.

The Beauty of Disproof: When Experiments Confirm the Opposite

The scientific method, at its core, is a rigorous process of testing hypotheses. Sometimes, the most significant discoveries arise not from confirming a cherished idea, but from attempting to disprove it and inadvertently proving it correct. This dynamic is vividly illustrated by the story of Robert Millikan and his experiments on the photoelectric effect. Millikan, driven by a desire to disprove Albert Einstein's nascent quantum mechanical theories, spent over a decade meticulously measuring the photoelectric effect. His goal was to build the "world's best experiment" to invalidate Einstein's predictions. Instead, his precise measurements confirmed Einstein's quantum hypothesis, leading to Millikan's own Nobel Prize.

This narrative underscores a crucial aspect of scientific progress: the commitment to empirical evidence, even when it contradicts deeply held beliefs or initial hypotheses. The consequence of such rigorous experimentation is the refinement and strengthening of our scientific models. It reveals that the beauty of science lies not in proving oneself right, but in the relentless pursuit of truth, wherever the evidence may lead. Conventional wisdom might suggest that scientists are driven by a desire to confirm their own theories, but the reality, as exemplified by Millikan, is often a dedication to the experimental outcome, regardless of its implications for their personal convictions.

"He spent 12 years measuring measuring this effect and at the end came out with the best possible measurement basically proving Einstein was right and he gets the Nobel Prize despite the fact that everything in him wanted it to work the other way."

-- Dr. Suzie Sheehy

The story of Millikan's experiment offers a powerful lesson in the value of delayed gratification and intellectual humility. The "payoff" for Millikan was not the vindication of his initial skepticism, but the Nobel Prize and a deeper understanding of quantum mechanics. This requires a patience and a willingness to accept unexpected results that many find difficult. The competitive advantage here lies in the scientific community's ability to embrace such outcomes, fostering an environment where disproof can lead to profound new understanding. This approach contrasts sharply with fields where dogma or ideology can resist empirical challenge, highlighting why science, when conducted rigorously, is such a powerful engine for progress.

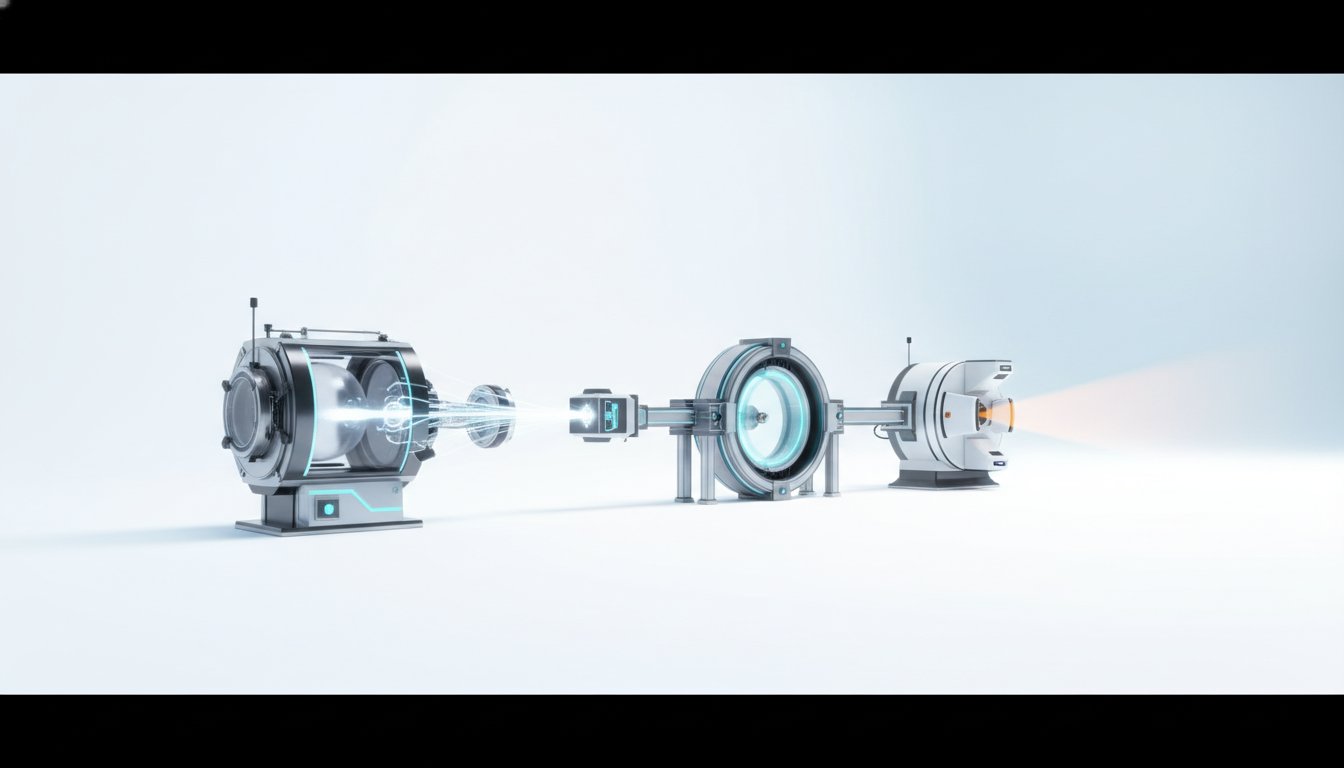

Accelerating Innovation: From Particle Colliders to Cancer Treatment

The technological byproducts of fundamental physics research often have far-reaching applications, transforming fields seemingly unrelated to the initial quest for knowledge. Particle accelerators, the massive machines used to probe the fundamental nature of matter, are a prime example. While the Large Hadron Collider at CERN represents the cutting edge of particle physics, the underlying technology has found its way into numerous applications, with medicine being one of the most impactful.

Approximately half of all cancer patients today are treated with radiotherapy, a technique that relies on particle accelerators to generate X-rays. These X-rays are directed at tumors to destroy cancer cells. However, X-rays also damage healthy tissue. More advanced forms of radiotherapy, such as proton therapy, use heavier particles like protons or carbon ions, which deposit their energy more precisely at a specific depth within the body, minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues. The challenge with these advanced therapies lies in the size and cost of the machines required. Dr. Sheehy's current research focuses on developing next-generation particle accelerator technologies that are smaller, cheaper, and faster, aiming to make these life-saving treatments more accessible.

"We have also in that time found ways to make that treatment even more accurate because x rays they will damage both the tumor cells which you want to target but they will also deposit dose in the healthy tissue and the the game that that oncologists play in treating cancer with radiation is trying to decrease the dose to healthy tissue and increase the dose to cancerous tissue."

-- Dr. Suzie Sheehy

This translation of fundamental research into practical applications demonstrates a powerful systems-level thinking. By understanding the technological bottlenecks in cancer treatment--such as the speed of treatment delivery--physicists can work backward to identify areas for innovation in accelerator design. This requires a long-term perspective, as developing these technologies can take years, with payoffs that might not be immediately apparent. The competitive advantage is significant: those who invest in and develop these advanced technologies, even when they are expensive and complex, can create durable solutions that improve patient outcomes and advance medical science. It requires a willingness to tackle difficult problems, where immediate discomfort in development leads to lasting benefits in patient care.

Key Action Items

- Immediate Action (Next Quarter): Re-evaluate your understanding of "contact." Consider how electromagnetic forces, not physical touch, govern your daily interactions. This mental reframing can enhance appreciation for fundamental physics.

- Immediate Action (Next Quarter): Seek out accessible explanations of dark matter and dark energy. Understanding the vastness of our cosmic ignorance can foster intellectual humility and curiosity.

- Short-Term Investment (Next 6 Months): Explore the history of a specific scientific experiment mentioned in The Matter of Everything (e.g., Millikan's photoelectric effect experiment). Analyze the motivations of the scientists involved and how their pursuit of disproof led to confirmation.

- Short-Term Investment (Next 6 Months): Research the role of particle accelerators in modern medicine, beyond basic radiotherapy. Understand the principles of proton therapy and its advantages.

- Medium-Term Investment (Next 12-18 Months): Investigate the concept of "accelerator physics" and its interdisciplinary applications. Consider how technologies developed for fundamental research can address real-world problems.

- Long-Term Investment (18+ Months): Support or engage with science communication initiatives that translate complex physics concepts for a general audience. This helps bridge the gap between scientific discovery and public understanding.

- Strategic Investment (Ongoing): Cultivate a mindset that embraces the possibility of being wrong. Recognize that the most significant scientific advancements often come from challenging existing paradigms, even when it's uncomfortable.