Paternal Lifestyle Influences Offspring Epigenetics Via Sperm RNA

The surprising truth about paternal influence is that it extends far beyond DNA. This conversation reveals that a father's lifestyle choices--his diet, exercise, and stress levels--may actively shape his offspring's biology through mechanisms previously confined to maternal influence. The hidden consequence is a profound shift in our understanding of inheritance, suggesting that men have a more direct, molecular role in their children's health and predispositions than ever imagined. This insight is crucial for anyone planning a family, offering a significant advantage by highlighting actionable steps to positively influence future generations, even before conception.

The Unseen Inheritance: How Dad's Habits Rewrite the Blueprint

For generations, the narrative of inheritance has been a one-sided affair: mothers contribute the cellular machinery and the environment of the egg, while fathers deliver a compact packet of DNA. This view, reinforced by the distinct roles of egg and sperm, painted paternal contribution as largely passive. The egg, a veritable powerhouse of cellular components, was understood to dictate much of the early development. Sperm, in contrast, was seen primarily as a delivery vehicle for half the genetic code. This perspective, however, is being fundamentally challenged by emerging research, suggesting that fathers actively package more than just genes into their sperm.

The traditional understanding of sperm is that it's a simple entity: a head containing DNA and a tail for propulsion, powered by a few mitochondria. The egg, by contrast, is a massive cell, rich with the cytoplasm and organelles necessary for early development. Crucially, all human mitochondria--the cell's energy factories--are maternally inherited, a fact that underscored the egg's dominant role. This established a clear biological baseline: the mother provides the cellular infrastructure, and the father provides the genetic instructions.

However, the story of inheritance is far more intricate. We now understand that beyond the DNA sequence itself, a complex layer of epigenetic regulation controls which genes are expressed and when. Epigenetics, in essence, is the "software" that runs on the "hardware" of our DNA. It involves physical molecules, like methyl groups, that bind to DNA, dictating whether genes are accessible for expression or silenced. This layer of control is influenced not only by programmed cellular processes but also by external factors--diet, exercise, stress, and environmental exposures. These factors alter the molecular composition of our cells, impacting gene expression.

"So that's what epigenetics tries to get at is like how do you take this base code and then shut off huge sections of it and turn on other sections so that some parts of the cell or some ingredients for that cell are created in some cells and not others?"

This is where the paternal contribution becomes a frontier of biological inquiry. While maternal health and habits are well-established influences on offspring development, the idea that paternal lifestyle choices could have a similar molecular impact has been met with skepticism. The prevailing view has been that sperm, being so specialized and seemingly devoid of the complex cellular machinery of the egg, could not possibly carry such information. Yet, a growing body of research, particularly in mouse models, points to a surprising reality: fathers' diets, exercise routines, and stress levels appear to be encoded in their sperm, influencing the traits and health of their offspring.

The Hidden Cost of Fast Solutions

The evidence for paternal epigenetic inheritance, while compelling, has been difficult to accept due to its counter-intuitive nature. For decades, studies in mice demonstrated that altering the father's diet or stress levels resulted in offspring exhibiting similar phenotypic changes--better processing of high-fat foods, or increased stress responses--even though the offspring's own environment was controlled. These observations were inexplicable under the traditional model of sperm as merely a DNA carrier.

"And the pups will have at least some large proportion of them will express similar phenotypes to their dad. Even though you think it's just the sperm that's getting transferred during this fertilization event, it's like, 'Well, how come some of these mice seem like they're better prepared to process high-fat foods or, you know, why are some of these mice acting really stressed out even though they've never experienced stress before because they're babies?'"

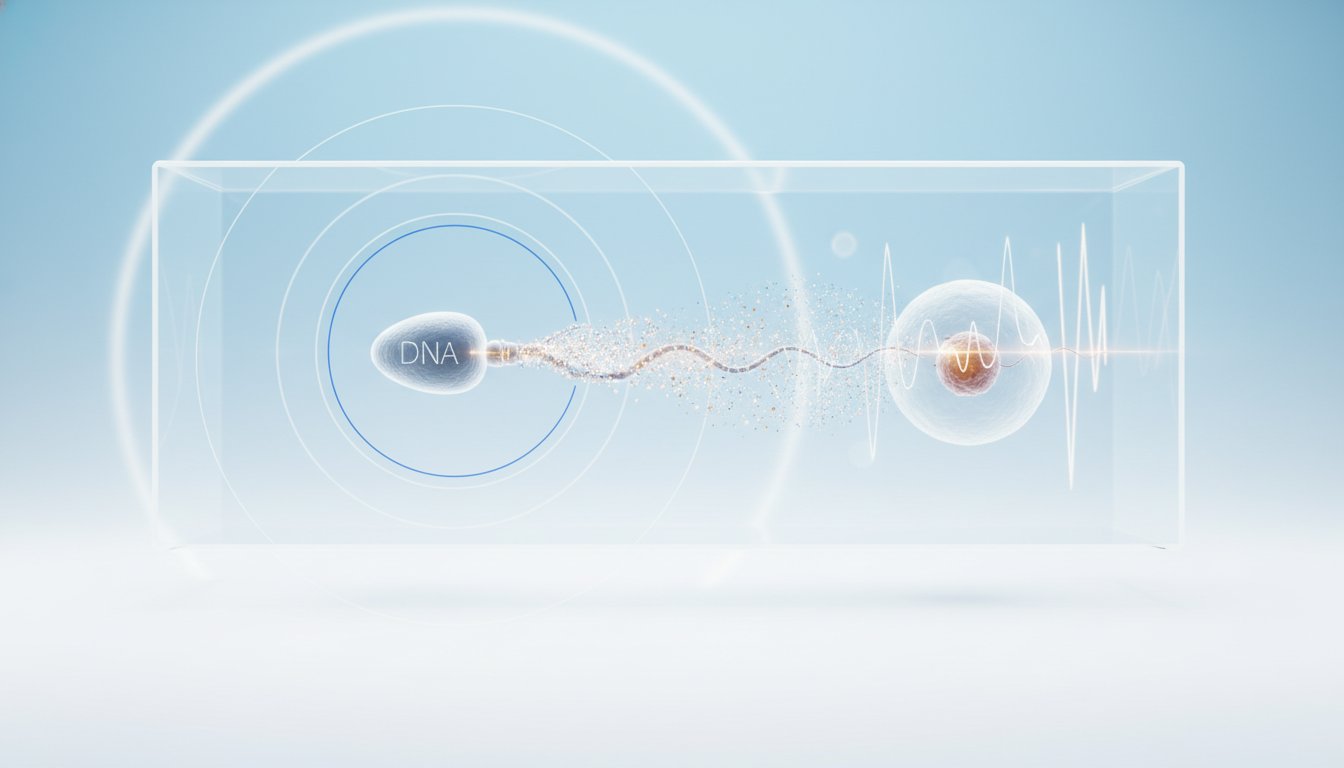

The breakthrough lies in understanding the maturation process of sperm. During their one to two-week journey through the epididymis, sperm cells develop their tails and acrosomes (the cap that helps them penetrate the egg). This maturation process is not solely about DNA packaging; it also involves the incorporation of molecules from the father's body, delivered via extracellular vesicles called epididymosomes. These vesicles, essentially tiny bubbles released by cells, can carry proteins and other molecules. The critical insight is that if a father's body composition changes due to diet, exercise, or stress, these changes can be reflected in the molecular cargo within these vesicles, which are then incorporated into the maturing sperm.

This mechanism provides a plausible pathway for paternal epigenetic inheritance. For instance, recent studies have identified specific microRNAs--small RNA molecules that regulate gene expression--in the sperm of well-exercised mice. These microRNAs were found to be active in the zygote (the fertilized egg) and appeared to interfere with the construction of proteins related to mitochondrial function and exercise physiology. This suggests that a father's fitness, at a molecular level, can be transmitted to his offspring, influencing their potential for exercise and metabolic health.

The challenge now is translating these mouse model findings into human understanding. Proving such inheritance in humans is exceptionally difficult, requiring multi-generational studies and precise tracking of molecular changes. Unlike controlled mouse experiments, human environments are complex, with myriad confounding factors.

"But we use mouse models because they are suggestive at the very least that that might be taking place in people."

This difficulty in direct human study is precisely why the mouse models are so valuable. They allow researchers to isolate variables and establish causal links that are obscured in human populations. The implications are profound: what were once considered purely maternal contributions to offspring health may, in part, be paternal. This reframes the concept of "preparing for conception," suggesting that men's lifestyle choices in the months leading up to conception could have a lasting, molecular impact on their children's well-being. The immediate discomfort of adopting healthier habits is a small price for the potential of creating a lasting biological advantage for future generations.

Key Action Items

- Immediate Action (Within the next month): Educate yourself and your partner on the principles of epigenetics and paternal influence. Understanding the "why" is the first step to behavioral change.

- Short-Term Investment (1-3 months): For men planning to conceive, begin a consistent exercise regimen. Focus on cardiovascular health and strength training. This pays off by potentially improving sperm RNA profiles.

- Short-Term Investment (1-3 months): Prioritize a balanced, nutrient-rich diet. Reduce intake of processed foods, excessive fats, and sugars. This directly impacts cellular composition and the molecules available for packaging into sperm.

- Immediate Action: Implement stress-management techniques. This could include mindfulness, meditation, or engaging in hobbies. Chronic stress can negatively alter molecular profiles transmitted via sperm.

- Medium-Term Investment (3-6 months): If planning for children, consider this period as a critical window for lifestyle optimization. Avoid alcohol and smoking, as these are known to negatively impact sperm quality and epigenetic markers.

- Long-Term Investment (6-18 months): For men who have recently fathered children, understand that the habits established during the preconception period may have had an impact. Continue healthy practices for any future family planning.

- Ongoing Investment (Lifelong): Recognize that healthy lifestyle choices are not just for personal benefit but can have intergenerational consequences. This perspective can provide powerful motivation for sustained healthy living.