Chagas Disease Neglect: A Systemic Failure Driven by Inequity

The Hidden Price of Neglect: How Chagas Disease Exposes Systemic Failures in Public Health and Immigration

This conversation with journalist Daisy Hernández, author of "The Kissing Bug," reveals a stark truth: the neglect of diseases like Chagas is not accidental but a consequence of deeply embedded systemic issues, particularly at the intersection of public health and immigration policy. The non-obvious implication is that our failure to address diseases disproportionately affecting marginalized communities creates not only immediate suffering but also long-term societal costs. Those who understand these dynamics--public health officials, policymakers, and healthcare providers--gain a critical advantage in advocating for equitable resource allocation and more effective, humane public health strategies. This exploration highlights how a disease that could be managed, especially in children, becomes a devastating, chronic burden due to a lack of attention and resources, ultimately underscoring the interconnectedness of social justice and global health.

The Invisible Burden: Why Chagas Disease Remains a Neglected Tropical Disease

The term "neglected tropical disease" is a diplomatic euphemism that masks a harsh reality: a deliberate underallocation of resources and attention to illnesses that primarily affect marginalized populations. Daisy Hernández’s deeply personal narrative, chronicling her aunt Dora’s struggle with Chagas disease, illuminates how this neglect is not merely an oversight but a consequence of systemic biases in global health agendas. Chagas disease, transmitted by the triatomine insect, or "kissing bug," affects an estimated 8 million people, predominantly in Latin America, yet remains largely unknown in the United States. This lack of awareness and funding stems from a historical tendency, particularly by Western nations, to categorize such diseases as "tropical" and therefore outside their immediate purview.

"The term neglected tropical disease it's kind of curious right because it's this big this big health organization that is telling us that it's neglected but you wonder you know sort of neglected by whom and why can't we change that"

-- Daisy Hernández

The disease’s insidious nature is compounded by its transmission vector. The parasite is not in the bite itself but in the insect's fecal matter, which can enter the body through the bite wound or by being rubbed into the eyes or mouth. In its acute phase, symptoms are often vague, mimicking the flu, leading to delayed diagnosis. This delay is critical because while the acute phase is treatable, the chronic stage, which affects 10-15% of those infected, can lead to severe cardiac or gastrointestinal problems. In Latin America, Chagas disease is the leading cause of heart disease, yet in countries like Brazil and Argentina, awareness often translates into a grim understanding: saving money for a pacemaker becomes a necessity. This foresight, born of experience, highlights a stark contrast with the general public’s ignorance.

The English name, "kissing bug disease," trivializes the devastating impact of the illness. While Spanish-speaking regions have more visceral names like "vinchuca" or "chinche," the Southwest United States has long known the insect as a "blood sucker," a more accurate descriptor of its parasitic nature. Hernández’s own childhood was shaped by this disease, acting as a child interpreter between her aunt and medical professionals. This early immersion in the disease’s realities, coupled with a lack of accessible information, fueled her later quest to write the book she wished she had at fifteen.

The Immigration Nexus: When Borders Become Barriers to Health

A critical, often overlooked consequence of Chagas disease’s neglect is its entanglement with immigration policy. Hernández argues that these are not separate issues but inextricably linked, particularly in the United States. The targeting of immigrants has created an environment of fear, deterring individuals from seeking essential medical care, including Chagas testing and treatment. Doctors are forced to be cautious about where they refer patients, as immigration agents have been known to appear in hospital settings, making healthcare facilities unsafe spaces for undocumented individuals.

"The targeting of immigrants has just become more and more vicious as we all know as time has gone on and so the impact means that you have especially just right now you have immigrants who are not going to be going out to seek medical care because they are afraid of what it means to go into a doctor's office or into an emergency room"

-- Daisy Hernández

This fear-driven avoidance means that individuals often wait until they are in emergency situations to access care, exacerbating their conditions and increasing the burden on emergency services. The COVID-19 pandemic, while a global health crisis, starkly illustrated that viruses and parasites do not respect borders. Yet, politically, the narrative often remains one of containment and exclusion, rather than shared public health responsibility. This intersection of immigration policy and public health creates a "second America," as Hernández describes, where a segment of the population lives with treatable or manageable diseases, largely invisible to the broader society, just miles from centers of power like Washington D.C.

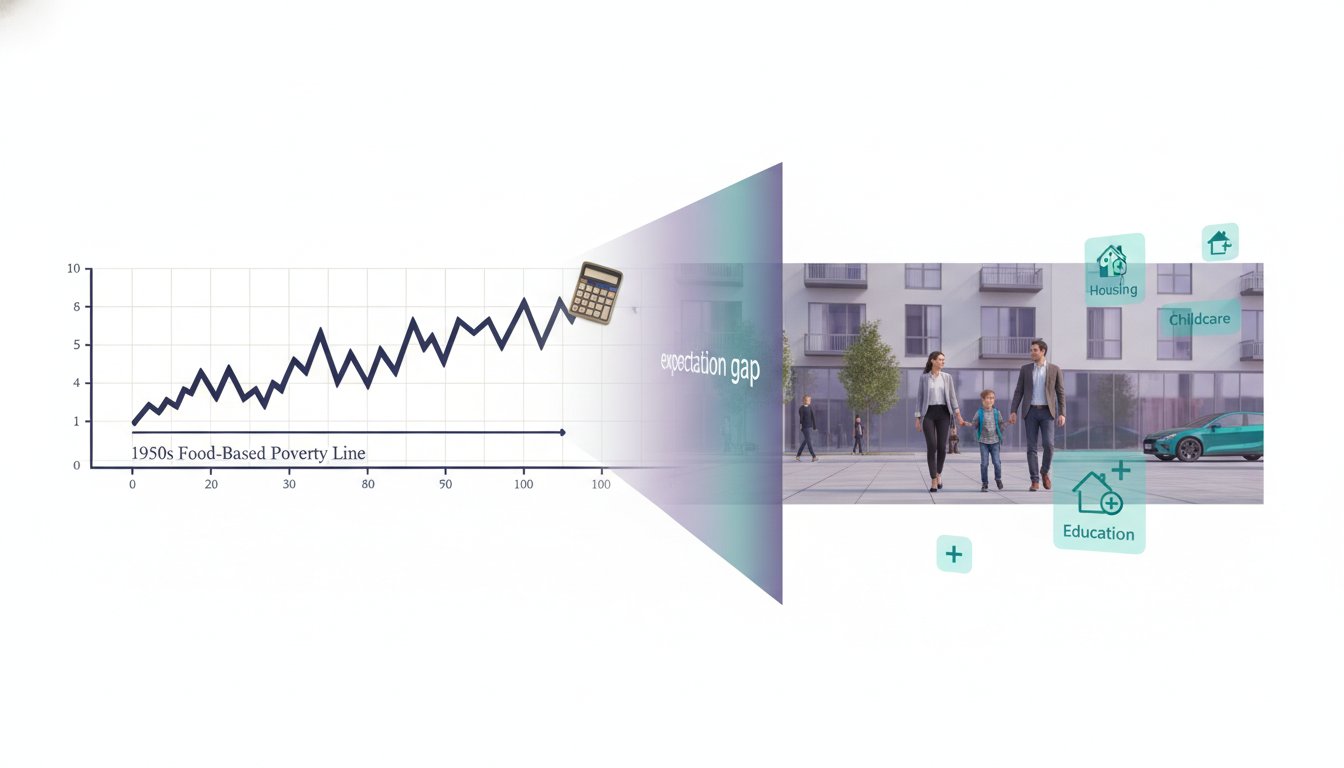

The Curative Gap: Children Treatable, Adults Left Behind

The disparity in treatment efficacy between children and adults with Chagas disease presents another layer of systemic failure. While there is no cure for adults in the chronic stage, curative medications are highly effective when administered to children or during the acute phase of the illness. However, prenatal screening for Chagas disease is not standard practice in the United States. This oversight means that an estimated 300 children per year may be born with the disease, missing a crucial window for intervention.

The reasons for the difference in treatment effectiveness between age groups are still being investigated by scientists, but the implication is clear: a proactive public health approach, including routine screening of pregnant women and newborns, could prevent the lifelong burden of chronic Chagas disease for many. Instead, the current system allows the parasite to progress, leading to irreversible cardiac or gastrointestinal damage in adulthood. This gap in care is a direct result of the disease’s neglected status, where research and preventative measures lag behind the potential for effective intervention.

Stigma and Silence: The Personal Cost of Neglect

Beyond the medical and policy failures, Chagas disease carries a significant social stigma, particularly for those who, like Hernández’s aunt Dora, immigrated to the U.S. Dora was terrified of anyone knowing she had Chagas, partly due to the time period she arrived in the U.S. (coinciding with the AIDS epidemic) and her own feelings of being an outsider as an immigrant. This fear of stigma, while not universally experienced by all patients Hernández interviewed, underscores how societal perceptions can further isolate individuals affected by neglected diseases. The reluctance to discuss the disease, even within families, perpetuates a cycle of silence and prevents the necessary public discourse and advocacy for greater attention and resources. Hernández’s book itself represents a courageous act of breaking this silence, bringing the story of her aunt and millions of others into the light.

Key Action Items

-

Immediate Action (Next 1-3 Months):

- Educate Yourself and Your Network: Share articles and resources about Chagas disease and other Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) with colleagues, friends, and family.

- Advocate for Screening: Encourage healthcare providers and public health organizations to consider Chagas disease screening for at-risk populations, particularly immigrants from endemic regions.

- Support Research Funding: Contact elected officials to advocate for increased federal funding for research into NTDs, including diagnostics and treatments for Chagas disease.

-

Short-Term Investment (Next 3-6 Months):

- Integrate NTD Awareness into Clinical Practice: Healthcare systems should develop protocols and training for clinicians to recognize symptoms and risk factors for Chagas disease.

- Community Outreach Programs: Partner with immigrant-serving organizations to conduct culturally sensitive outreach and testing events for Chagas disease in at-risk communities.

-

Long-Term Investment (6-18 Months & Beyond):

- Policy Reform for Prenatal and Pediatric Screening: Advocate for the implementation of routine prenatal and pediatric screening for Chagas disease in the United States to identify and treat children early.

- Global Health Equity Initiatives: Support and promote global health initiatives that prioritize funding and research for diseases disproportionately affecting low-income countries and marginalized populations, challenging the "tropical" and "neglected" labels.

- De-stigmatization Campaigns: Develop and support public awareness campaigns that aim to reduce the stigma associated with Chagas disease and other NTDs, normalizing conversations about these illnesses. This discomfort now, in acknowledging and discussing these diseases, creates a lasting advantage in public health equity.