Jigsaw Puzzles: Cognitive Enhancement and Social Bonding Across Centuries

TL;DR

- Jigsaw puzzles evolved from Enlightenment-era educational tools for spatial reasoning into psychological stabilizers during the Great Depression, offering a sense of control and community during uncertainty.

- The transition from wooden, non-interlocking puzzles to cardboard, die-cut, interlocking pieces in the early 20th century democratized puzzle-making, dramatically lowering costs and increasing accessibility.

- Three-dimensional puzzles enhance cognitive function by engaging spatial reasoning, working memory, and executive functions, strengthening skills crucial for STEM fields and complex problem-solving.

- Puzzling fosters self-efficacy and flow states by providing immediate feedback and a sense of accomplishment, intrinsically motivating individuals through the problem-solving process itself.

- Collaborative puzzling strengthens social bonds by creating a structured environment for communication, negotiation, and shared strategy, fostering trust and group cohesion without competition.

- Engagement with cognitively demanding leisure activities like puzzles is linked to building cognitive reserve, potentially slowing the decline of visual-spatial abilities and executive functioning in aging.

Deep Dive

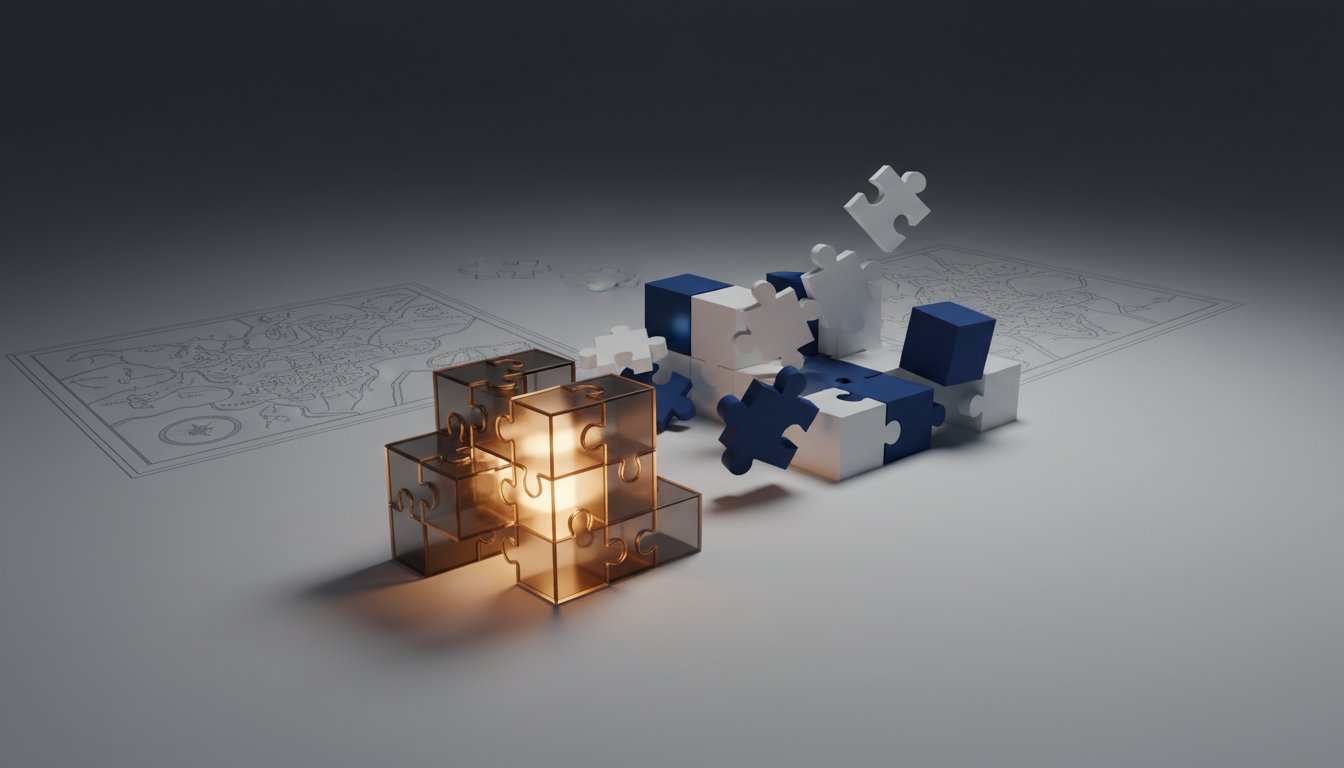

The jigsaw puzzle, far from a simple pastime, has evolved from an Enlightenment-era educational tool into a sophisticated mechanism for cognitive enhancement and social bonding. Its history reveals a continuous adaptation to technological advancements and societal needs, underscoring its enduring value in developing critical thinking, spatial reasoning, and emotional well-being.

The puzzle's origins trace back to the 1760s with John Spilsbury, a British mapmaker who cut maps along national borders to create "dissected maps" for teaching geography. These early iterations, essentially maps disassembled and reassembled, established the foundational elements of challenge, visual division, and discovery. Initially, these were expensive, handcrafted wooden pieces without interlocking features, serving as elite educational tools. By the 19th century, puzzles transitioned into parlors, becoming a popular Victorian leisure activity, though still largely without interlocking pieces and accessible primarily to the wealthy due to their artisanal nature. The advent of the mechanical jigsaw saw in the late 1800s popularized the term "jigsaw puzzle," but true democratization arrived with two key 20th-century innovations: the development of interlocking pieces around 1908 and the shift from wood to cardboard. This transition dramatically lowered costs and standardized production, making puzzles accessible to the masses.

During the Great Depression, jigsaw puzzles became a national phenomenon, offering an affordable escape and a sense of control amidst widespread economic instability. Libraries lent puzzles, and families gathered to assemble them, providing a "national stabilizer" and a quiet source of hope. Post-World War II advancements in die-cutting further streamlined production, solidifying puzzles as a staple for family gatherings. The mid-to-late 20th century saw increased piece counts and the introduction of themed puzzles, including psychedelic art and pop culture scenes.

The most significant second-order implications arise from the evolution of three-dimensional puzzles. These puzzles act as multi-domain cognitive workouts, engaging spatial reasoning, mental rotation, and the ability to visualize objects across depth and orientation. This process strongly activates parietal lobe regions associated with STEM fields and problem-solving. Furthermore, 3D puzzles demand sustained attention on multiple constraints like gravity and balance, strengthening working memory and executive functions such as planning and task switching. The inherent trial-and-error nature of puzzling provides error-based learning, enhancing cognitive flexibility and resilience. Research in aging and cognition suggests that such cognitively demanding activities, particularly those involving novelty and sustained engagement like 3D puzzles, contribute to cognitive reserve, potentially slowing the decline of visual-spatial abilities and executive functioning often seen in normal aging. Beyond cognition, puzzles foster metacognitive awareness, cultivate a sense of mastery and competence, and reduce stress through their intrinsically rewarding problem-solving nature.

Socially, puzzles function as cooperative problem-solving environments that naturally foster bonding, communication, and shared strategy. Unlike competitive games, puzzles encourage participants to work toward a common goal, strengthening interpersonal trust and group cohesion by requiring coordination and joint attention. This collaborative aspect lowers social pressure, allowing interaction to emerge organically through shared focus and small successes, acting as a "social scaffolding" that reinforces patience, persistence, and collective achievement. Therefore, the jigsaw puzzle's enduring appeal lies not just in its simple act of assembly, but in its profound capacity to cultivate individual cognitive skills and strengthen social connections across centuries and technological shifts.

Action Items

- Create 3D puzzle prototype: Test spatial reasoning and working memory enhancement using 5-10 example puzzle pieces (2-week sprint).

- Draft runbook template: Define 5 required sections (setup, common failures, rollback, monitoring) to prevent knowledge silos for puzzle creation processes.

- Audit puzzle design: Analyze 3-5 puzzle sets for inclusion of whimsical or hidden pieces to assess engagement beyond standard piece count.

- Measure puzzle impact: Track 5-10 participants' self-efficacy and flow state engagement during 2D and 3D puzzle completion.

Key Quotes

"Spilsbury worked with printed maps mounted on thin sheets of mahogany one day and historians are not entirely sure whether it was a flash of pedagogical brilliance and accidental slip of the saw or an attempt to amuse a restless student spilsbury took a fine marketry saw and cut out each country along its border suddenly the geography became tactile a child could now pick up spain place it next to france and experience the spatial relationships that textbooks could only describe thus the world's first dissected map the ancestor of the jigsaw puzzle was born"

Gabrielle Birchak explains that John Spilsbury, an 18th-century cartographer, created the first "dissected map" by cutting maps into wooden pieces. This innovation transformed geography from abstract information into a tangible, spatial learning experience for children. Birchak highlights that this early form of the puzzle established the foundational elements of challenge, visual division, and discovery.

"by the 1880s the puzzle became commonly known as the jigsaw around the same time that the fret saw became the tool to create the shapes of the puzzle the name only emerged when the mechanical jigsaw saw became the preferred cutting tool for puzzle makers by the mid century the industrial revolution brought improvements in printing and woodworking that made puzzles more widely available still puzzle making was laborious artisanal work it wouldn't be democratized until the arrival of a very special cutting technology in the early 20th century"

Gabrielle Birchak details the evolution of the puzzle's name and manufacturing. Birchak notes that the term "jigsaw" became common when the mechanical jigsaw saw replaced the fret saw for cutting. Birchak explains that while the Industrial Revolution made puzzles more accessible, true democratization, meaning widespread affordability and availability, was delayed until early 20th-century technological advancements in cutting.

"first there was the interlocking piece so around 1908 puzzle makers began designing true interlocking tabs and blanks those are the little knobs and sockets that keep pieces from sliding apart this changed everything second cardboard replaced wood so by the early 20th century manufacturers realized that printed images could be mounted on cardboard and die cut rapidly using metal presses conveniently this shift lowered costs dramatically standardized the piece shapes and made puzzles accessible to the masses"

Gabrielle Birchak identifies two pivotal developments that democratized jigsaw puzzles in the early 20th century. Birchak explains that the introduction of interlocking pieces around 1908, featuring "tabs and blanks," significantly improved puzzle stability. Birchak also notes the shift from wood to cardboard, which, combined with mass production techniques like die-cutting, drastically reduced costs and made puzzles accessible to a much wider audience.

"for those living in the united states during the 1930s chances are they either worked long hours worried constantly like we do now or solved jigsaw puzzles or often all three during the darkest years of the great depression jigsaw puzzles became a nationwide phenomenon because puzzles were affordable not only did the libraries start lending out puzzles which they still do today the great depression puzzles were very inexpensive also puzzles gave people a sense of control when the world was falling apart people could still make one small picture fall back together again"

Gabrielle Birchak describes the significant role of jigsaw puzzles during the Great Depression in the United States. Birchak explains that their affordability, even leading to library lending, made them accessible during a time of economic hardship. Birchak highlights that puzzles provided a crucial sense of control and accomplishment for individuals facing widespread uncertainty and a world that felt like it was falling apart.

"research from cognitive psychology neuroscience and aging studies converges on several well supported benefits first there's spatial reasoning and mental rotation three dimensional puzzles strongly engage spatial reasoning the ability to understand and manipulate objects in space solvers must mentally rotate pieces predict how shapes will align along multiple axes and visualize hidden surfaces that are not immediately visible"

Gabrielle Birchak outlines the cognitive benefits of three-dimensional puzzles, drawing from research in psychology and neuroscience. Birchak emphasizes that these puzzles significantly enhance spatial reasoning and mental rotation skills. Birchak explains that solvers must mentally manipulate pieces, predict alignments across multiple dimensions, and visualize unseen surfaces, which activates brain regions crucial for spatial cognition.

"puzzles also align closely with the concept of flow a mental state in which challenge and skill are balanced attention is fully absorbed and the individual experiences enjoyment rooted not in external reward but in the act of problem solving itself this combination of effort feedback and mastery helps explain why finishing a puzzle feels deeply satisfying even without prizes or competition"

Gabrielle Birchak discusses the psychological concept of "flow" as it relates to puzzling. Birchak explains that flow is a state of complete absorption where challenge and skill are balanced, leading to enjoyment derived from the activity itself, not external rewards. Birchak suggests this intrinsic satisfaction, stemming from effort, feedback, and mastery, is why completing a puzzle feels so deeply rewarding.

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "Hypatia: The Sum of Her Life" by Gabrielle Birchak - Mentioned as a book available for purchase on Amazon.

Articles & Papers

- "The History of Jigsaw Puzzles" (Math! Science! History! Podcast) - The primary subject of the episode.

People

- Gabrielle Birchak - Host of the Math! Science! History! podcast.

- John Spilsbury - English cartographer credited with creating the first dissected maps, ancestors of the jigsaw puzzle.

Organizations & Institutions

- Math! Science! History! - Podcast discussed in the episode.

- Pixabay - Source for music used in the podcast.

Websites & Online Resources

- mathsciencehistory.com - Website for the Math! Science! History! podcast, mentioned for additional information and merchandise.

- a.co/d/g3OuP9h - Amazon link for the book "Hypatia: The Sum of Her Life".

- bsky.app/profile/mathsciencehistory.bsky.social - Bluesky profile for Math! Science! History!.

- instagram.com/math.science.history - Instagram profile for Math! Science! History!.

- facebook.com/mathsciencehistory - Facebook profile for Math! Science! History!.

- linkedin.com/company/math-science-history/ - LinkedIn profile for Math! Science! History!.

- threads.com/@math.science.history - Threads profile for Math! Science! History!.

- mathstodon.xyz/@mathsciencehistory - Mastodon profile for Math! Science! History!.

- youtube.com/@mathsciencehistory - YouTube channel for Math! Science! History!.

- pinterest.com/mathsciencehistory - Pinterest profile for Math! Science! History!.

- mathsciencehistory.com/the-store - Link to the merchandise store for Math! Science! History!.

- mathsciencehistory.supercast.com - Platform for ad-free listening and bonus content for Math! Science! History!.

- mathsciencehistory.com/transcriptorium - Location for podcast transcripts.

Other Resources

- Acoustic Sheep Sleep Phones - Headphones mentioned as comfortable for sleeping to audio content.

- Coffee!! - Mentioned as a way to support the Math! Science! History! podcast via PayPal.

- The Little Prince - A work by Lloyd Rodgers, mentioned as a source of music.