Misinterpretation of True Data: A Greater Danger Than Misinformation

TL;DR

- Misinterpreting true data is 41 times more dangerous than outright misinformation, leading to flawed decision-making by creating inaccurate lessons learned from experiences.

- Explanatory satisfaction, the feeling of an explanation being "right," can override critical thinking, causing individuals to accept biased or incorrect conclusions without further interrogation.

- Base rate neglect, the tendency to ignore statistical probabilities in favor of specific, often irrelevant, descriptive details, leads to poor forecasting and decision-making.

- The illusion of certainty, a preference for confident pronouncements over probabilistic assessments, hinders effective decision-making in a fundamentally uncertain world.

- Self-selected samples, like studying only successful individuals or products, create survivorship bias, obscuring the full picture and leading to flawed conclusions about causality.

- Educational systems should shift from fact-based memorization to decision-based skills, teaching probabilistic thinking and critical data interrogation from an early age.

- Communicating uncertainty effectively requires providing lower and upper bounds alongside point estimates, revealing what is known and unknown to foster better understanding and inquiry.

Deep Dive

Decision-making is fundamentally a probabilistic forecast, yet humans are hardwired for certainty, leading to systemic errors in interpreting data. This inherent cognitive bias, amplified by the information-rich modern world, causes individuals and organizations to misinterpret information, leading to flawed conclusions and suboptimal outcomes.

The core issue is not necessarily outright misinformation, but rather the pervasive tendency towards "misinterpretation," where true data is twisted or misunderstood due to cognitive biases like "explanatory satisfaction" and "resulticism." This leads to flawed causal reasoning, such as assuming correlation equals causation, as seen in the Washington Post article on COVID-19 deaths or a client's marketing strategy success. The danger lies in these misinterpretations becoming the basis for critical decisions in health, finance, and business.

The implications are far-reaching:

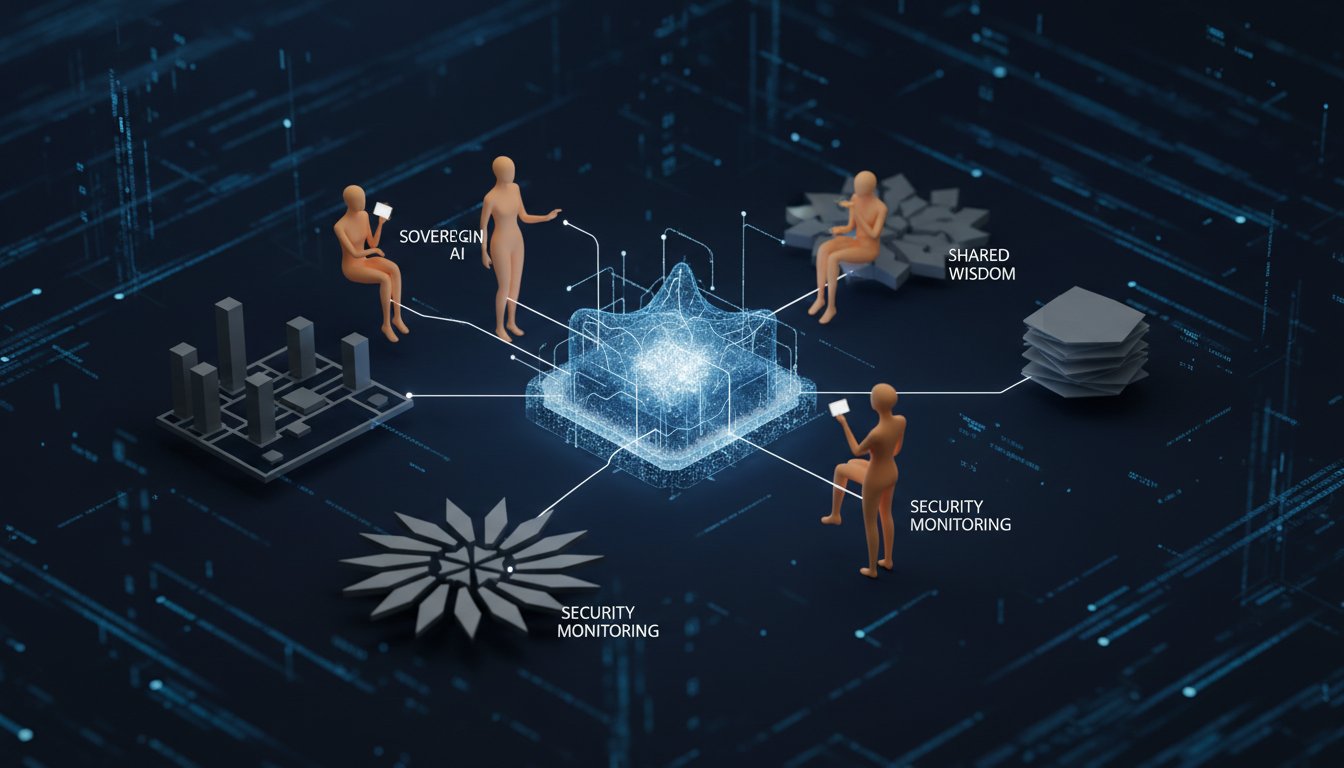

* Systemic Decision Errors: The reliance on intuitive, biased interpretations over rigorous data interrogation leads to poor strategic choices. This is exacerbated by AI, which can generate plausible but incorrect explanations if not prompted with skepticism.

* Educational Deficiencies: Traditional education prioritizes fact memorization over critical decision-making skills like probabilistic thinking, counterfactual analysis, and bias identification. This leaves individuals ill-equipped to navigate a complex, probabilistic world.

* The Illusion of Certainty: Humans crave certainty, leading them to favor confident pronouncements over nuanced probabilistic assessments. This makes them susceptible to misleading narratives and hinders their ability to update beliefs based on new evidence.

* The "Survivor Bias" Trap: People naturally look to successful examples for guidance, but this overlooks the vast majority who followed similar paths without achieving success. This self-selected sampling leads to flawed lessons and an overestimation of controllable factors like "making one's own luck."

Ultimately, improving decision quality requires a fundamental shift towards probabilistic thinking and a rigorous "interrogation" of data, moving beyond the comfort of satisfying explanations to embrace the uncertainty inherent in forecasting. This necessitates a proactive approach to education and personal development, focusing on asking the right questions rather than accepting immediate answers.

Action Items

- Audit data interpretation: For 3-5 key business metrics, analyze 10-15 recent reports for misinterpretations or misleading conclusions, focusing on "out of how many" and "compared to what" questions.

- Implement probabilistic thinking training: Develop and deliver a 1-hour workshop for 5-10 team members on understanding and applying probabilistic reasoning to decision-making, using examples from the text.

- Create a "data interrogation checklist": Draft a 5-7 item checklist for evaluating data sources and conclusions, emphasizing questions like "What is the denominator?" and "Is the sample representative?"

- Design a "counterfactual analysis framework": For 2-3 recurring strategic decisions, document potential counterfactual scenarios and their implications to encourage deeper analysis beyond immediate explanations.

- Evaluate AI output critically: For 3-5 AI-generated insights used in decision-making, document the prompts used and cross-reference findings with at least two other sources to assess reliability.

Key Quotes

"At the core of every decision is a forecast. Everything is a bet. There's a set of possible outcomes, and a payoff associated with each. That's how we calculate the expected value toward your goals. The explanation we often jump to is inaccurate because we don't know how to interrogate the data."

Annie Duke explains that decisions are fundamentally about forecasting future outcomes, which involves assessing probabilities and potential payoffs. She highlights that our tendency to quickly accept explanations without rigorous examination of the underlying data often leads to inaccurate conclusions and poorer decision-making.

"What Duncan Watts found is that it's 41 to 1. The misleading thing, the misinterpretation, is actually the bigger problem. When I saw that, this actually had aligned with something that had made me really mad, which was an article that I read in The Washington Post in 2022, where I really felt this problem of, 'Look, if you think about it, I don't think that the majority of people are trying to lie to you.'"

Annie Duke points out that misinterpretation of information is a more significant issue than outright misinformation, citing research by Duncan Watts. She uses this to frame her argument that people often arrive at misleading conclusions not because they are intentionally lying, but because they lack the skills to properly interpret the data presented to them.

"The Washington Post headline caught my eye because of that, because it was basically in friction with what I knew their bias was. The title of the article was, 'COVID is No Longer a Pandemic of the Unvaccinated.' I mean, I really perked up. I was like, 'What? Whoa! What kind of data is in this?'"

Annie Duke recounts her reaction to a specific Washington Post headline, noting its contradiction with the publication's known biases. This anecdote serves to illustrate how a seemingly counterintuitive headline can pique interest and prompt a deeper investigation into the data presented, especially when it challenges pre-existing assumptions.

"So I said, 'Well, okay, wait, I'm going to keep reading. There must be, because they're going to tell me what percentage of the population are vaccinated, right?' Like, obviously, no, they did not. So I was like, 'All right, let me go look that up.' So I went and looked it up because it wasn't in the article, which made me very upset."

Annie Duke describes her process of critically examining the Washington Post article, emphasizing the importance of seeking out missing context, such as the vaccination rates of the population. Her frustration at this crucial data point being omitted highlights her belief that incomplete information, even if factually presented, can lead to significant misinterpretations.

"The Washington Post article cited that in August of that year, 58% of the people who had died of COVID were vaccinated, 42% were not. So the reporter, having seen this, and go fact-check it, it's true. You can fact-check for August of 2022, you'll see that that's true. This is the problem, but the old quant in me is just red flag, your head is just floating."

Annie Duke presents the core data from the Washington Post article, confirming its factual accuracy but immediately signaling her concern as a "quant" (quantitative analyst). This quote sets up her subsequent analysis, where she demonstrates how true data, presented without proper context, can lead to a misleading conclusion.

"So I was like, 'Okay, well, wait, just, let's just start here. 80% of the population is vaccinated, 58% of the people who had died of COVID are vaccinated. Let's look at it from the other frame. 20% of the population is unvaccinated, and they accounted for 42% of the deaths.'"

Annie Duke illustrates the critical step of reframing data by incorporating the population vaccination rate. By comparing the percentage of deaths among vaccinated individuals to the overall vaccinated population, and similarly for unvaccinated individuals, she begins to reveal the misleading nature of the original headline.

"Then I was like, 'Well, okay, if I really wanted to take a step further, I ought to age-match.' Because obviously, older people are both more likely to be vaccinated and more likely to die of COVID than younger people. There was a statistician who had done, somebody else had gotten upset about the article, and they did do the age-matching, and it turned out that you were five times more likely to die if you were unvaccinated of COVID in the month that The Washington Post declared that COVID was no longer a pandemic of the unvaccinated."

Annie Duke explains the necessity of further data refinement through age-matching, acknowledging that age is a confounding factor in both vaccination rates and COVID-19 mortality. She then presents a statistician's finding that, after age-matching, unvaccinated individuals were significantly more likely to die from COVID-19, directly contradicting the article's headline.

"I just said, 'I don't think this reporter is trying to lie. I just think they don't know how to interrogate data.' So they see this data, and they don't know the questions to ask, the most simple of which would be, 'Out of how many?' which was the first question I asked."

Annie Duke reiterates her belief that the reporter's error stemmed from a lack of data interrogation skills, not malicious intent. She emphasizes the fundamental question, "Out of how many?", as the crucial first step in properly interpreting any statistic, underscoring the importance of understanding denominators.

"So I sort of call it crossing the chasm, from description, 'Okay, you've shown me a description, this is how many in each year,' to explanation, 'These marketing strategies caused this thing to occur.' That's an explanation. But there's this big thing in between that you've just crossed the chasm, interrogation."

Annie Duke uses the metaphor of "crossing the chasm" to describe the leap from merely presenting descriptive data to asserting an explanatory cause. She argues that the critical, often skipped, step between these two is interrogation, where the data is rigorously examined to validate the proposed explanation.

"I'm guessing to a lot of people that when I sort of describe this situation, they're like, 'Well, isn't that obvious?' But I can show you why it's not obvious pretty easily. I could say, 'What if I had an arrow there and it said, 'Russia invaded Ukraine'?' Would you fall for this? The answer, of course, is no, because there's this great concept in cognitive psychology, Tanya Lombroso talks about this, called explanatory satisfaction."

Annie Duke suggests that the leap from description to explanation can seem obvious in retrospect but is often flawed. She introduces the concept of "explanatory satisfaction," a psychological phenomenon where a compelling explanation, even if unsupported, feels satisfying and is readily accepted, often confirming existing biases.

"It's when an

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "Thinking in Bets" by Annie Duke - Mentioned as a previous work by the author that discusses how interpreting experiences can lead to biased conclusions.

- "Quit" by Annie Duke - Mentioned as a book that emphasizes the importance of pre-commitment contracts and kill criteria to stop doing things faster.

- "Outlive" by Peter Attia - Mentioned as a source that discusses a famous example of hormone replacement therapy risks.

- "The Millionaire Next Door" - Mentioned as an example of a book with a self-selected sample, leading to potentially misleading conclusions about habits and success.

- "Good to Great" - Mentioned as an example of a book with a self-selected sample.

Articles & Papers

- "Covid is no longer a pandemic of the unvaccinated" (The Washington Post, 2022) - Mentioned as an article that presented data on COVID-19 deaths in a misleading way due to a lack of context.

People

- Annie Duke - Former professional poker player and author, discussed for her work on decision-making, forecasting, and interpreting data.

- Duncan Watts - Mentioned for his research dividing misinformation into two categories: outright falsehoods and misinterpreted information, with the latter being a larger problem.

- Tanya Lombroso - Mentioned in relation to the concept of "explanatory satisfaction."

- Phil Tetlock - Mentioned for his work on "superforecasters" and forecasting competitions.

- Bart Miller - Mentioned in relation to "Good Judgment Project" and forecasting competitions.

- Peter Attia - Mentioned as a source for an example regarding hormone replacement therapy risks.

- Lori Santos - Mentioned for her insights on happiness, specifically regarding the impact of nature and phone usage on conversations.

- Eric Corbet - Mentioned as a board member from Microsoft working on a decision co-pilot tool.

Organizations & Institutions

- Alliance for Decision Education - Mentioned as an organization that has developed an AI tool to embed decision skills into lesson plans and runs forecasting competitions for students.

- Penn - Mentioned as the institution where Duncan Watts is located.

- Microsoft - Mentioned as the employer of Eric Corbet.

- CNN - Mentioned in the context of prediction markets.

- CNBC - Mentioned in the context of prediction markets.

- Yale - Mentioned as the institution where Lori Santos works.

Other Resources

- Decision Quality - Discussed as a key factor in determining life outcomes, alongside luck.

- Forecasts - Described as being at the core of every decision, involving a set of possible outcomes and associated payoffs.

- Expected Value - Mentioned as a calculation based on possible outcomes, payoffs, and probabilities.

- Resulting Problem - Described as a bias where poor outcomes lead to drawing incorrect conclusions about decision quality.

- Misinformation - Divided into two categories: outright falsehoods and misinterpreted information.

- Propaganda - Mentioned as a type of misinformation.

- Motivated Reasoning - Mentioned as a type of misinformation.

- Bots - Mentioned as a type of misinformation.

- Data Visualization - Mentioned as a tool used in data generation.

- Efficacy of Vaccines - Mentioned as an example of data that can drive personal decisions.

- Explanatory Satisfaction - A cognitive psychology concept where an explanation feels satisfying, often confirming existing biases or beliefs.

- Cognitive Biases - Mentioned as a factor that can drive explanations and lead to inaccurate conclusions.

- Availability Bias - Mentioned as a heuristic that can become problematic in a globalized world.

- Illusion of Certainty - The preference for candidates who make certain pronouncements, even when uncertainty exists.

- Prediction Markets - Discussed as a tool that could be used to assess certainty and provide probabilistic forecasts.

- Trigonometry - Mentioned as a subject that could be replaced by statistics and probability in education.

- Statistics and Probability - Proposed as core decision skills that should be taught in education.

- Counterfactuals - Mentioned as a decision skill that can be embedded into lesson plans (e.g., "what if" scenarios).

- Agency - Discussed as a concept that can be taught to children, emphasizing their role as agents of their own decisions.

- Optionality - Mentioned as a decision skill that can be taught.

- Base Rate - Discussed as a fundamental concept in forecasting and statistics, often neglected.

- Pragmatics - A part of linguistics concerning how context influences meaning, relevant to how extra information is interpreted.

- Conjunction Fallacy - A cognitive bias where people incorrectly assume that two events are more likely to occur together than either individual event.

- Framing Effect - The tendency for people to react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how it is presented (e.g., as a loss or as a gain).

- Information Theory - Mentioned in relation to Claude Shannon's concept that information is unexpected.

- Social Cohesion - The reliance on believing people are generally telling the truth for societal functioning.

- Sunk Cost Fallacy - The tendency to continue an endeavor as a result of previously invested resources (time, money, or effort), even when it's no longer rational.

- Pre-commitment Contracts - Agreements made in advance to limit future choices and overcome biases.

- Kill Criteria/Stopping Rules - Predefined conditions under which an activity or endeavor will be stopped.

- Randomized Control Trial (RCT) - A study design used to minimize bias and determine the effectiveness of an intervention.

- Self-Selected Sample - A sample where participants choose themselves, potentially leading to biased results.

- Vitamin E Supplementation - Used as an example of how self-selection bias can lead to misleading conclusions about health benefits.

- Hydroxychloroquine - Mentioned as a drug with significant adverse effects, highlighting the importance of RCTs.

- Statins - Mentioned as a drug with generally lower side effects, but still requiring consideration of risks and benefits.

- The Great Reshuffle - A series of discussions about societal and economic changes.

- Clockwork World - A deterministic view of the world where cause and effect are linear and predictable.

- Probabilistic World - A view of the world where outcomes are uncertain and influenced by chance.

- Luddite Movement - Mentioned as an example of resistance to technological change.

- Rain Dances - Mentioned as a ritual to overcome randomness.

- Heuristics - Mental shortcuts used for decision-making.

- Encycopedia - Mentioned as a historical source of information.

- Retricular Activating System (RAS) - Mentioned in relation to scanning for opportunities.

- Monte Carlo Simulation - A computational technique that uses random sampling to obtain numerical results.

- Conjunction Fallacy - Mentioned again in relation to linguistics and pragmatics.

- Decision Co-pilot - A type of tool that assists in decision-making.

- LLMs (Large Language Models) - Discussed in the context of their potential for providing biased or inaccurate information.

- Social Media - Compared to AI in terms of its objective to maximize engagement.

- Perplexity - Mentioned as an AI model that generally does not default to biased answers.

- Oceon Score - Mentioned in the context of hiring engineers.

- Mini Bernedoodle - The breed of the host's dog, Otis.