Nuanced Handicapping: Class Drops, Jockeys, and Track Conditions Drive Success

This conversation offers a masterclass in strategic thinking, particularly for those involved in competitive environments, from horse racing handicappers to business strategists. Bobby Newman, the host of "Betting with Bobby," dissects race outcomes and conditions, revealing a consistent pattern: the most successful approaches are rarely the most obvious or comfortable ones. The non-obvious implication here is that true advantage is forged not by chasing immediate wins, but by understanding and leveraging the downstream consequences of decisions, often by embracing short-term difficulty for long-term gain. This analysis is crucial for anyone looking to gain a competitive edge, offering a framework for anticipating market shifts, competitor actions, and the hidden costs of seemingly simple solutions. It’s for the strategist, the analyst, and the competitor who understands that the real game is played in the second and third order of effects.

The Hidden Currents of Competitive Advantage

The world of horse racing, as presented by Bobby Newman on "Betting with Bobby," is a microcosm of broader competitive landscapes. Success isn't merely about picking the fastest horse; it's about understanding the intricate systems at play -- the track conditions, the jockey's strategy, the horse's history, and crucially, the subtle ways in which these elements interact to produce an outcome. What emerges from this detailed race-by-race analysis is a powerful lesson in consequence mapping and systems thinking: the most effective strategies often involve embracing immediate discomfort for delayed, and often amplified, rewards. This is where true competitive advantage is built, not on the obvious, but on the unseen currents that shape the race.

The "Drop" and the Illusion of Easy Wins

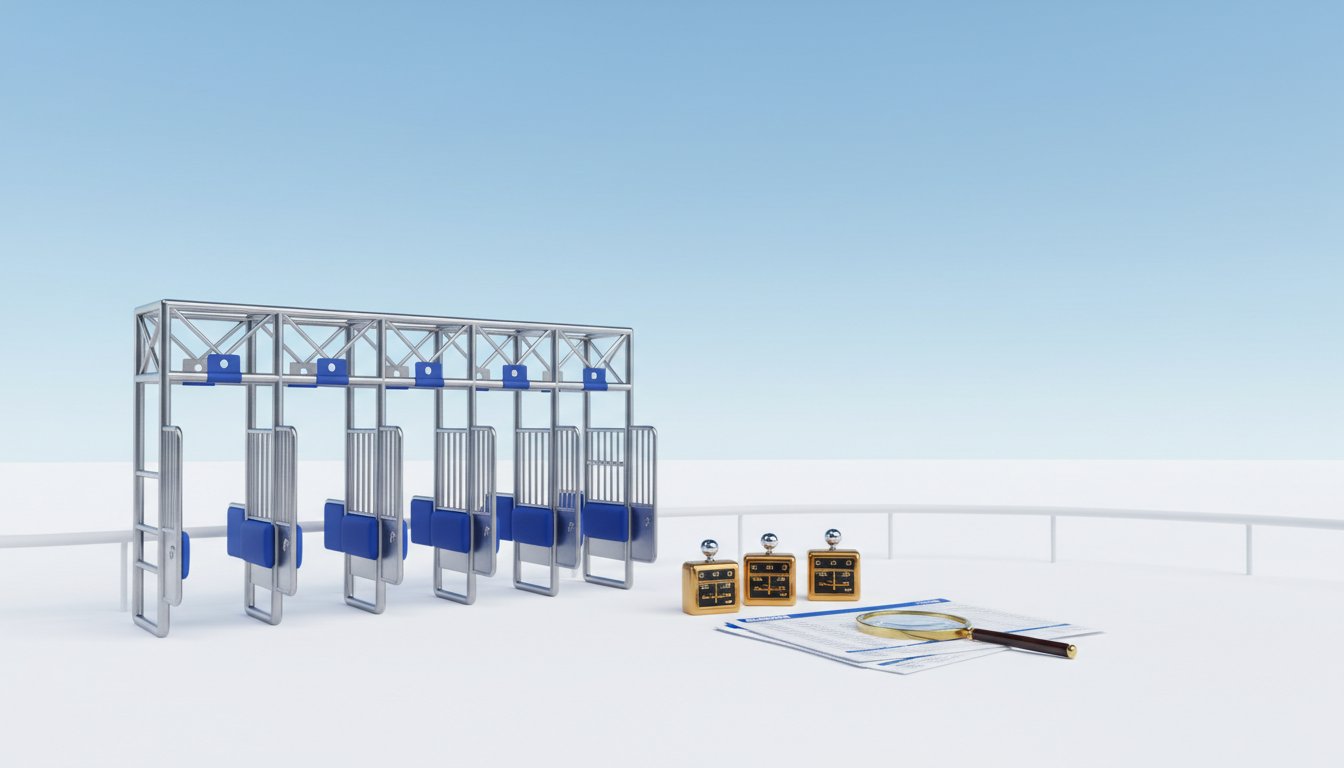

One of the most frequently cited "sayings" in racing, as Newman notes, is "There's no hop like the drop." This refers to a horse dropping in class, moving from maiden special weight or allowance races into maiden claiming. On the surface, this appears to be a straightforward path to victory. The horse is perceived as being "better than them," and the odds reflect this expectation. However, the transcript subtly underscores the danger of this simplistic view. When Delaterra, the favorite in Santa Anita's second race, drops into maiden claiming, she battles for the lead and holds on at a short price. While she wins, the narrative hints at the effort required and the narrow margin. This isn't a guaranteed "hop"; it's often a hard-fought victory against competitors who are also trying to exploit a perceived advantage. The immediate reward of a win is achieved, but the underlying system--the competitive nature of racing--ensures that even "easier" paths demand significant effort and can still lead to close finishes. The true insight here is that chasing the obvious "drop" can mask underlying vulnerabilities or simply lead to a race that is harder than anticipated, rather than the easy win it promised.

"One of the older sayings in racing is, 'There's no hop like the drop,' and this seems to be the drop that people think is the biggest drop in racing, going from straight maiden, straight maidens, or maiden allowance, or maiden special weight, whatever you want to call it, into maiden claiming competition for the first time."

This highlights how conventional wisdom, when applied without deeper analysis, can lead to predictable, yet not always optimal, outcomes. The "drop" is an immediate perceived benefit, but it doesn't account for how other horses might adapt or how the competition level, even within claiming races, can be surprisingly robust.

The Long Game: Delayed Payoffs and Strategic Patience

The analysis of the Lecomte Stakes offers a glimpse into the long-term implications of success. Newman points out that while the Lecomte is a significant race on the path to the Kentucky Derby, "strangely enough, there has never been a winner of the Lecomte Stakes who has gone on to win the Kentucky Derby." This is a powerful example of a delayed payoff structure. Winning the Lecomte is an immediate success, a stepping stone. But the ultimate prize--the Kentucky Derby--has eluded its winners. This suggests that the conditions or preparation that lead to Lecomte success might not perfectly align with the demands of the Derby.

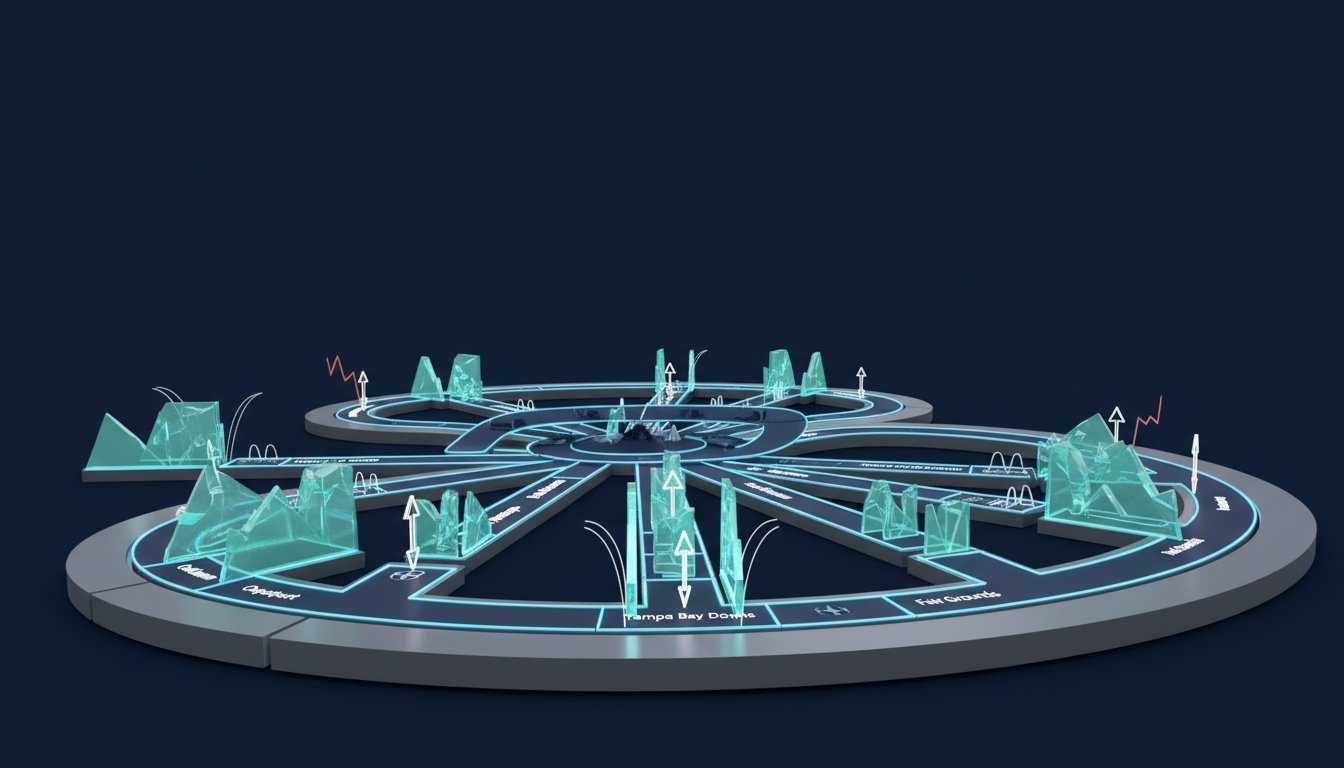

Similarly, in the Tampa Bay Downs Race 8, Dancing Magic wins at nine to five, a price that wasn't among the initial favorites. This implies a late surge of confidence or a strategic advantage that wasn't immediately apparent. The horse's victory, while immediate, is the culmination of factors that might not have been evident at first glance. The transcript doesn't explicitly detail the long-term trajectory of these horses, but the structure of the sport itself--with its series of races and championships--inherently rewards strategic patience. Horses that are developed with a long-term view, rather than being pushed for immediate wins, often achieve greater sustained success. This is where a competitive advantage is built: by understanding that today's effort might not yield today's victory, but it lays the groundwork for a more significant win down the line.

When Conventional Wisdom Fails: The Turf-to-Synthetic Shift

A recurring theme, particularly at Gulfstream Park, is the decision to move races off the turf and onto the synthetic track, even when the weather seems favorable. Newman expresses frustration with this, calling it "ridiculous" and suggesting the turf is being "saved" for more prestigious weekend races. This decision, while perhaps strategically sound for the track's long-term maintenance and marketing, creates a cascading effect. Horses that are conditioned for turf may not perform as well on synthetic surfaces. The "obvious" choice for a handicapper might be to bet on a horse that excels on turf, but the system's decision to alter the conditions forces a re-evaluation.

"They're saving the turf course is what it is. They're saving it for weekend races, and then of course they've got a monster card, the Pegasus card, a week from tomorrow. So they're foregoing these cheaper races, if you will, and forcing them to be run on the synthetic track."

This illustrates how external systemic decisions--like track maintenance or scheduling--can disrupt conventional handicapping strategies. The immediate consequence for the bettors is uncertainty and potential loss if they stick to old assumptions. The underlying lesson is that adaptability and a willingness to question conventional wisdom, especially when the underlying conditions change, are paramount. The horses that can perform adequately on both surfaces, or those whose connections anticipate these shifts, gain an advantage. This requires foresight and an understanding that the "rules of the game" can change, often for reasons that aren't immediately apparent to the casual observer.

Embracing the "Hard Line": The Value of Difficult Choices

The transcript occasionally touches upon horses that, despite not being favorites, find a way to win, often through determined effort. In Fair Grounds Race 6, Starry Eyed wins at eight to one, with jockey Erica Murray, who had a slow start to her meet. This suggests that success isn't always correlated with immediate popularity or established form. Sometimes, it's the horse that grinds out a win, or the jockey who perseveres through a difficult period, that ultimately triumphs.

In Aqueduct Race 8, Cavana, the favorite, wins despite looking like he might be in trouble. He drifts wide, but ultimately proves strongest. This suggests that even when a favorite faces adversity, their underlying quality or the strategic advantage of class drop can prevail. The "hard line" here is sticking with a horse that shows the potential for strength even when challenged, rather than abandoning it at the first sign of trouble. This mirrors the idea that competitive advantage is often built by pushing through difficulty. The trainers and jockeys who are willing to make tough decisions, to run horses in challenging conditions, or to stick with a strategy that requires patience, are the ones who often reap the greatest rewards. The transcript, through its detailed race calls, implicitly celebrates these moments of resilience and strategic execution, reminding us that the most valuable victories are often the hardest-won.

- Embrace the "Drop" with Caution: Recognize that a class drop is an immediate perceived advantage, but analyze if other factors (track condition, distance, competition) negate it. Do not assume an easy win.

- Analyze Delayed Payoffs: Consider the long-term potential of horses or strategies. Races like the Lecomte highlight that immediate success doesn't always translate to ultimate victory.

- Adapt to Changing Conditions: Be aware of how external factors (like track surface changes) can impact performance and adjust your analysis accordingly, rather than relying on past assumptions.

- Value Resilience: Look for horses and connections that demonstrate perseverance. Victories achieved through overcoming adversity or executing a difficult strategy often indicate deeper competitive strength.

- Question Conventional Wisdom: The "hop like the drop" is a common saying, but the transcript shows that even favorites can face challenges. Dig deeper than the obvious narrative.

The Unseen Mechanics of Racing

The detailed race calls from "Betting with Bobby" reveal a complex interplay of factors that extend far beyond the immediate action at the finish line. Bobby Newman’s commentary, while focused on the races themselves, offers a window into the underlying systems that govern outcomes. This isn't just about picking winners; it's about understanding how decisions cascade, how seemingly minor factors can have significant downstream effects, and how true advantage is often built on a foundation of foresight and strategic patience.

The System's Response to the "Drop": More Than Just Class

The frequent mention of horses dropping in class, particularly into maiden claiming races, highlights a common strategy. Delaterra, for instance, is noted as moving into maiden claiming competition for the first time after facing tougher maiden races. The immediate assumption is that this class reduction will lead to an easier win. However, the transcript subtly points out that this isn't a guaranteed path to victory. Delaterra battles for the lead and ultimately wins by a narrow margin. This suggests that while the class drop offers a perceived advantage, the "system" of racing responds in complex ways. Other horses in that class level are also competitive, and the effort required to win can still be substantial.

"Delaterra actually finished second twice in those four starts against tougher competition. Her last three starts have been on turf. She's getting back onto the dirt for the first time since her debut, and she has to deal with the rail, which she didn't deal with very well last time out. We'll see if she gets a better trip today, dropping in class, short field."

This quote reveals the layers of analysis required. The class drop is one factor, but the horse's prior performance, surface preference, post position, and the quality of the competition within the claiming ranks all contribute to the outcome. The immediate benefit of the class drop is tempered by these other systemic influences. The implication is that simply identifying a class drop is insufficient; one must analyze how the horse and the competition will perform within that new system.

The Long Game of Horse Development: Beyond the Immediate Win

The discussion around the Lecomte Stakes provides a crucial insight into the limitations of focusing solely on immediate gains. Newman highlights that no winner of the Lecomte has ever gone on to win the Kentucky Derby. This suggests that the preparation and racing style that leads to Lecomte success might not be conducive to winning the ultimate prize. The Lecomte represents an immediate victory, a significant achievement on the road to the Triple Crown. However, the horses that win it may be peaking too early or developing in a way that doesn't translate to the greater demands of the Kentucky Derby.

This illustrates a core principle of systems thinking: solutions optimized for one part of a system may not work for the whole. In this context, winning the Lecomte is a "first-order" success. But the ultimate goal is the Kentucky Derby, a "second-order" outcome that requires a different strategic approach. The horses that are strategically developed for the entire Triple Crown, even if they don't win every stepping stone race, might have a better chance at the ultimate prize. This delayed payoff structure is where true competitive advantage lies -- in understanding the long-term trajectory and making decisions today that set up future success, even if it means foregoing immediate accolades.

Navigating the Synthetic Shift: Systemic Rigidity vs. Adaptability

The repeated mention of races being taken off the turf at Gulfstream Park, despite favorable weather, reveals a systemic rigidity. Newman expresses frustration, noting that the turf course is likely being "saved" for weekend races. This decision, while perhaps logical from a track management perspective, creates a new set of conditions that horses and handicappers must navigate. Horses that excel on turf may struggle on the synthetic surface, and vice-versa.

"They're saving the turf course is what it is. They're saving it for weekend races, and then of course they've got a monster card, the Pegasus card, a week from tomorrow. So they're foregoing these cheaper races, if you will, and forcing them to be run on the synthetic track."

This situation highlights how systemic decisions, even those seemingly unrelated to the immediate competition, create downstream effects. The trainers and owners who have horses with versatility across surfaces, or who can adapt their training and race selection to these shifts, gain an advantage. The handicappers who anticipate these changes and adjust their analyses accordingly are better positioned to succeed. The conventional wisdom of betting on a turf specialist is rendered obsolete by the system's decision. This forces a re-evaluation, rewarding those who can adapt and penalize those who rigidly adhere to outdated assumptions. The "obvious" choice becomes the wrong choice when the underlying system changes.

The "Hard Line" of Competition: Where Discomfort Breeds Advantage

The transcript often features races where the outcome is hard-fought, with favorites facing challenges or longshots emerging victorious. In Fair Grounds Race 6, Starry Eyed wins at eight to one with jockey Erica Murray, who was having a slow start to her meet. This suggests that success can come from unexpected places and that persistence in the face of difficulty is rewarded. Similarly, in Aqueduct Race 8, Cavana, the favorite, wins despite looking troubled, demonstrating a resilience that ultimately prevails.

These instances underscore a critical principle: competitive advantage is often forged in moments of difficulty. The trainers who push their horses through tough training regimens, the jockeys who maintain focus during challenging races, and the handicappers who analyze horses that overcome adversity are often the ones who find success. The transcript doesn't explicitly state that these horses chose discomfort, but their victories in challenging circumstances imply a robustness that is valuable. The "hard line" isn't about seeking pain, but about recognizing that the path to victory in a competitive system often involves navigating obstacles and that overcoming them creates a durable advantage that others may not possess. This is where the "unpopular but durable" strategies emerge -- those that require patience and resilience, qualities that are difficult to replicate.

- Action Item: When analyzing a horse dropping in class, assess its performance on the new class level and consider the competition within that specific bracket, not just the perceived ease of the drop.

- Action Item: For horses targeting major races like the Kentucky Derby, evaluate their long-term development plan, not just their performance in early prep races. This requires looking beyond immediate wins to sustained potential.

- Action Item: Monitor track surface changes and their implications. Favor horses with proven versatility across surfaces or those whose connections have demonstrated an ability to adapt training and racing strategies.

- Action Item: Identify horses that have overcome adversity (e.g., difficult trips, tough competition, slow starts to a meet) as indicators of resilience and potential for future success.

- Action Item: Develop a framework for evaluating "second-order" consequences of decisions, such as how a track's maintenance schedule might affect race conditions and outcomes.

Key Quotes

"One of the older sayings in racing is, 'There's no hop like the drop,' and this seems to be the drop that people think is the biggest drop in racing, going from straight maiden, straight maidens, or maiden allowance, or maiden special weight, whatever you want to call it, into maiden claiming competition for the first time."

-- Bobby Newman

"Strangely enough, there has never been a winner of the Lecomte Stakes who has gone on to win the Kentucky Derby."

-- Bobby Newman

"They're saving the turf course is what it is. They're saving it for weekend races, and then of course they've got a monster card, the Pegasus card, a week