Fediverse Offers User Control Amidst Decentralization Challenges

TL;DR

- The Fediverse enables users to retain ownership of their online identity and content, mitigating the power of centralized social media moguls by allowing migration between servers without losing followers.

- Building a Fediverse instance, like "The Forkiverse," requires significant technical setup and ongoing moderation, highlighting the complexity behind creating functional, decentralized social spaces.

- Federated social networks offer a counter-narrative to algorithm-driven content by prioritizing user control and open protocols, potentially fostering healthier online interactions than current platforms.

- The experiment of creating "The Forkiverse" revealed that even with AI assistance, establishing and managing a social media server involves human oversight for community guidelines and moderation.

- The Fediverse's appeal lies in its potential to escape the "misery addiction" of current platforms and its ability to connect disparate communities, offering a more open internet experience.

- A key tension exists between the Fediverse's nostalgic appeal for older internet experiences and the need for it to offer genuinely new and compelling functionality to attract widespread adoption.

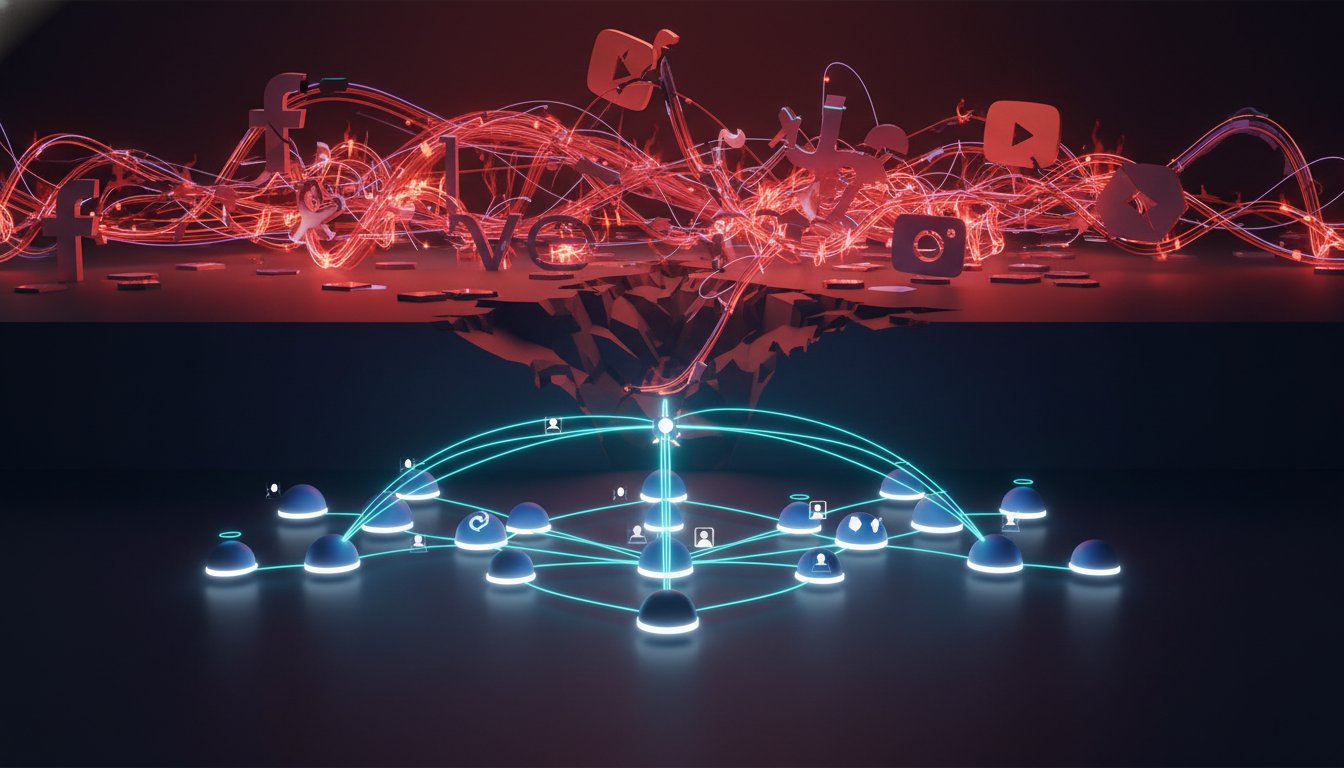

Deep Dive

The core argument is that the current internet, dominated by a few large social media platforms, actively harvests user attention by appealing to negative instincts, leading to a sense of "gooner's remorse" and a loss of user agency. To counter this, the podcast explores the Fediverse, an open, federated network, through a practical experiment: creating and launching a small social media instance called "The Forkiverse." The experiment highlights both the potential of the Fediverse to offer users greater control, portability, and a less algorithmically driven experience, and the significant challenges in explaining, accessing, and populating such a nascent ecosystem.

The experiment with "The Forkiverse" reveals several second-order implications regarding the nature of social media and user engagement. Firstly, the very act of creating a Fediverse instance, even with AI assistance, underscores the technical hurdles and the need for user-friendly tools to make this alternative accessible to the average person. The initial "pristine emptiness" of The Forkiverse, while appealing in its lack of misinformation and toxicity, also demonstrates the "chicken and egg" problem of network growth: without users, the platform is inert, and without content, it's unappealing. This highlights that the success of the Fediverse hinges not just on its architecture but on cultivating a community and a compelling reason for users to migrate or participate.

Secondly, the exploration of existing Fediverse content, from celebrity accounts to the Auschwitz Memorial and Elon Musk's jet tracker, illustrates the eclectic and often nostalgic nature of current Fediverse users, many of whom are seeking to recapture the perceived magic of older internet platforms. This backward-looking tendency presents a tension with the need for the Fediverse to offer something demonstrably new and better to attract a broader audience. The ability to "fork off" from the internet, or migrate one's presence without losing followers, is presented as a key practical advantage, offering an escape from the lock-in effects of centralized platforms. However, the experience of The New York Times firewall blocking access to The Forkiverse also points to the systemic inertia and gatekeeping that even alternative internet structures can encounter.

Ultimately, the experiment poses the question of whether the Fediverse can evolve beyond its current user base, which appears largely composed of "Twitter discontents" and millennials longing for a past internet experience, to become a genuinely novel and superior alternative. The success of The Forkiverse, and by extension the Fediverse, will likely depend on its ability to bridge the gap between its idealistic promises of user control and portability and the practical challenges of adoption, community building, and offering a distinct, compelling experience that transcends nostalgia.

Action Items

- Design server onboarding flow: Implement a 3-step process for new users to define their interests and connect with 5-10 relevant federated accounts.

- Audit server moderation policy: Define 3 core principles for content moderation and establish a 24-hour response time for reported issues.

- Track user engagement metrics: Measure daily active users and post frequency for the first 2 weeks to identify early adoption patterns.

- Evaluate federation capacity: Test connectivity with 5 diverse federated platforms to ensure seamless content aggregation for users.

- Develop user retention strategy: Create a plan to encourage content creation and community interaction for the first 100 users.

Key Quotes

"The problems with our internet are so well known, it feels dumb to summarize them. Like, who is the person left alive who needs me to explain to them that our 2026 internet is dominated by a few social media platforms who are brilliant at harvesting our attention by appealing to our worst instincts? We all know this. We've all experienced the kind of gooner's remorse after we've spent more time than we meant to mindlessly thumbing a feed that makes us feel worse about ourselves, our friends, the world."

PJ Voght articulates a widely recognized problem with the current internet, which is the dominance of social media platforms that exploit user attention for profit. Voght highlights that this issue is so pervasive that it is almost cliché to complain about it, yet it continues to worsen. This sets the stage for exploring potential solutions.

"The way they saw it, in the 90s, even in the early 2000s, our internet had truly been an open place, infinite websites, infinite message boards, populated by all sorts of people with all sorts of values, free to live how they wanted in the little neighborhoods they'd made. If you wanted to move homes on that internet, say switch your email from Yahoo to Gmail, it was a mildly annoying but not a huge deal. But then social media arrived."

Voght describes a perceived golden age of the internet where it was an open and decentralized space. This interpretation contrasts sharply with the current internet landscape, which Voght characterizes as more closed and dominated by social media platforms. The shift to social media, as described by Voght, fundamentally changed user experience and control.

"But the architects of the Fediverse, they had a more radical idea. The vision they held was that they could take control of social media out of the hands of the Musks and Zuckerbergs and reroute it back towards a more open internet where no mogul would ever have the same kind of power they do now."

Voght explains the core ambition of the Fediverse's creators: to decentralize power away from large tech moguls. This radical idea aims to restore a more open internet, preventing any single entity from wielding the immense influence currently held by figures like Musk and Zuckerberg. The Fediverse is presented as a direct challenge to the established social media order.

"On our normal internet, if you want to follow a friend to read their tweets, you have to sign up for an account on X.com, Elon Musk's platform. You have to follow his rules. You have to trust him with your direct messages. By default, you're offered posts in the order his algorithm chooses. On the federated internet, if you have a friend microblogging on a federated platform like Mastodon, you can follow their account from anywhere in the Fediverse. You don't ever have to join Mastodon itself."

This quote, from Voght, illustrates a key functional difference between the traditional internet and the Fediverse. Voght highlights how the Fediverse allows users to follow content across different platforms without being tied to a single proprietary service, contrasting this with the closed, algorithm-driven nature of platforms like X. This emphasizes the user freedom and interoperability offered by the Fediverse.

"For me, if right now, you know, very early into our, I don't even want to say reporting, like understanding of what the dream these people are trying to describe is, like my understanding is that basically one of the problems with the social media internet we've built is that the platform you show up on is going to guide acceptable behavior. Like Twitter is going to make you think in bumper stickers. Instagram's going to make you realize that everyone you know is thinner and on vacation or whatever. And that the sort of boundaries of what kind of person we can be and how we can interact with each other are set by the platforms."

Casey Newton identifies how current social media platforms dictate user behavior and interaction. Newton explains that the design of platforms like Twitter and Instagram shapes how users think and present themselves, setting boundaries on acceptable conduct. This observation underscores Newton's interest in exploring alternative platforms that might foster healthier interactions.

"To me, what is interesting about this is less about who will show up and what will they say on the network, but what can we connect our server to? Right? To me, this is the promise of the Fediverse. It's not like, could we set up an internet forum where people were nicer to each other and only said like pro-social things about the future of democracy? It's what happens if you're able to link it to some publications that publish news that you think is interesting and link it up to maybe another social network like Threads and see content from people who are posting there but nowhere else."

PJ Voght emphasizes that the true potential of the Fediverse lies not just in creating a space for nicer interactions, but in its ability to connect disparate online communities and content sources. Voght argues that the Fediverse's strength is its interoperability, allowing users to link to news publications and other social networks, thereby creating a richer and more diverse online experience than isolated platforms can offer. This highlights the network effect as a key promise of the Fediverse.

"The pristine emptiness of our site. Obviously, every social media platform has begun unsullied, but my real hope with the Forkiverse, if anyone did show up to use it, and who knew, but if they did, what might stop it from becoming what every other platform had become was that it wasn't particularly algorithmic. There was no AI-powered machine mind underneath it constantly trying to suggest addictive content to users. We had a social media that was not designed to make everyone miserably addicted to it."

Kevin Roose reflects on the initial state of their created Fediverse server, "the Forkiverse." Roose notes that, like all platforms, it began empty but expresses hope that its non-algorithmic, non-addictive design will prevent it from succumbing to the same issues as existing social media. This points to a deliberate design choice to avoid the addictive engagement loops common on other platforms.

"The thing that I have noticed, because I've been spending a little bit of time with Mastodon in general, trying to figure out who to follow, is that so much of it is just people trying to like recapture the magic of old Twitter. Like a lot of it just does feel like very backward-looking and like if we could all just get together on our new place and post like we used to, it could be like summer camp again. Yeah, and in this way where I'm like, I think like we need a new thing. Like I think whatever comes next has to feel different than what came before."

Casey Newton observes that much of the activity on Mastodon, a Fediverse platform, seems driven by nostalgia for older internet experiences, particularly "old Twitter." Newton suggests that this backward-looking sentiment might hinder the Fediverse's growth, arguing that a truly successful next-generation platform needs to feel novel and offer something distinctly new, rather than merely replicating

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "The New York Times App" by The New York Times - Mentioned as an example of a well-designed app that exposes users to diverse content.

Articles & Papers

- "Platformer" by Casey Newton - Mentioned as Casey Newton's website, which discusses social media moderation decisions.

- "Techmeme" - Mentioned as a popular news aggregator about tech news.

- "The Verge" - Mentioned as a tech news website.

- "404 Media" - Mentioned as a tech news publication.

People

- PJ Vote - Host of the podcast "Search Engine," collaborated on an experiment to build a social network on the fediverse.

- Casey Newton - Co-host of the podcast "Hard Fork" and writer behind "Platformer," collaborated on an experiment to build a social network on the fediverse.

- Kevin Roose - Co-host of the podcast "Hard Fork," collaborated on an experiment to build a social network on the fediverse and acted as CTO for the project.

- Ezra Klein - Mentioned in relation to a studio in the New York Times San Francisco bureau.

- Stephen Fry - Mentioned as a popular account on Mastodon.

- Auschwitz Memorial - Mentioned as a popular account on Mastodon.

- NASA - Mentioned as having a popular Mastodon account.

- Elon Musk - Mentioned in relation to his private jet tracker account on Mastodon and his platform X.

- Josh - Mentioned in relation to NASA's Mastodon account.

- Natalie Kitroeff - Mexico City bureau chief for The New York Times, discussed her reporting on the Sinaloa Cartel and fentanyl production.

- Sruti P - Collaborated on the "Search Engine" podcast.

- Garrett Graham - Senior producer for "Search Engine."

- Emily Molter - Associate producer for "Search Engine."

- Arman Bazarian - Composed and mixed original theme music for "Search Engine."

- Natsumi A - Fact-checked the "Search Engine" episode.

- Leah Reese Dennis - Executive producer for "Search Engine."

- Rob Murandy - Part of the team at Odyssey.

- Craig Cox - Part of the team at Odyssey.

- Eric Donally - Part of the team at Odyssey.

- Colin Gainer - Part of the team at Odyssey.

- Mora Curran - Part of the team at Odyssey.

- Josefina Francis - Part of the team at Odyssey.

- Kurt Courtney - Part of the team at Odyssey.

- Hillary Schoff - Part of the team at Odyssey.

Organizations & Institutions

- The New York Times - Mentioned for its app and its firewall system.

- The Sinaloa Cartel - Subject of reporting by Natalie Kitroeff.

- Odyssey - Production company for "Search Engine."

Websites & Online Resources

- The Forkiverse (theforkiverse.com) - A social media server created as part of an experiment, hosted on Mastodon.

- Mastodon - A federated social media platform used to build the Forkiverse server.

- Geocities - Mentioned in relation to Kevin Roose's past experience as a webmaster.

- X (formerly Twitter) - Mentioned as a closed social media platform and the subject of user dissatisfaction.

- Instagram - Mentioned as a closed social media platform.

- Threads - Mentioned as Meta's Twitter clone and a closed social media platform.

- Lemmy - Mentioned as a federated social media platform similar to Reddit.

- Pixelfed - Mentioned as a federated social media platform similar to Instagram.

- Substack - Mentioned as a platform that was left by a user who was able to take their subscribers with them.

- Squarespace - Used as an analogy for Mastodon's managed hosting service.

- Incognito Mode - A subscription option for the "Search Engine" show.

Podcasts & Audio

- Hard Fork - A podcast that collaborated on the Forkiverse experiment.

- Search Engine - A podcast hosted by PJ Vote, which collaborated on the Forkiverse experiment.

- The Great Search Engine Pod - Mentioned as a podcast hosted by PJ Vote.

Other Resources

- Fediverse - A network of federated social media platforms.

- AI Chatbots - Mentioned in relation to Kevin Roose's experiment communicating with them.

- Operator (OpenAI) - An AI tool used to help set up the Forkiverse server.

- Fentanyl Production - Subject of reporting by Natalie Kitroeff.

- Content Moderation - Discussed in relation to social media platforms and the Forkiverse.

- Social Media Algorithms - Discussed as a driving force behind current social media platforms.

- Federation Capacity - A technical specification for the Forkiverse server.

- DNS Records - A technical component for setting up a server.

- Cloudflare - Mentioned in relation to a security warning about the Forkiverse connection.