Sustaining Drive: Fulfillment in Process, Not Just Outcome

TL;DR

- Internalizing that achievement won't bring lasting happiness preserves drive by distinguishing fleeting joy from the deeper fulfillment found in the challenging process of pursuing meaningful goals.

- Finding fulfillment in tedious but important work requires reframing it as a necessary process, amplifying enjoyable moments, and reminding oneself of the larger, positive outcome.

- Maintaining core habits with minimum effective doses during intense periods prevents the establishment of bad habits, allowing for easier re-engagement with routines post-season.

- Distinguishing normal training fatigue from chronic exhaustion involves establishing personal norms for exertion and recovery, and addressing deviations that linger beyond a day or two.

- Balancing post-race recovery anxiety involves finding a minimum effective dose of activity to maintain fitness and mental health, avoiding prolonged inactivity or premature return to intense training.

Deep Dive

The pursuit of achievement offers fleeting happiness, not lasting fulfillment. While the drive to win is deeply ingrained and necessary for high performance, internalizing that external validation won't provide sustained satisfaction allows for a more balanced approach. This distinction is crucial for navigating demanding careers and personal goals, as true fulfillment stems from the process and the intrinsic value derived from meaningful work, rather than solely from the outcome.

This principle extends to managing the inherent tedium in many professions, such as medicine, law, or research. The key is to reframe the "boring" tasks not as obstacles, but as essential components of a larger, meaningful pursuit. By understanding that these repetitive duties enable growth, development, or contribute to a greater good, individuals can derive satisfaction from their contribution, even if the day-to-day work lacks excitement. Amplifying and cherishing the enjoyable aspects of the work -- client interactions, problem-solving, or direct impact -- can further sustain motivation. However, in knowledge work, a unique challenge arises when tedious tasks encroach upon and interrupt moments of deep focus or enjoyable work. To combat this, consciously chunking days into periods for focused "good" work and separate periods for "tedious" tasks is vital, protecting the quality of engaging work and preventing burnout.

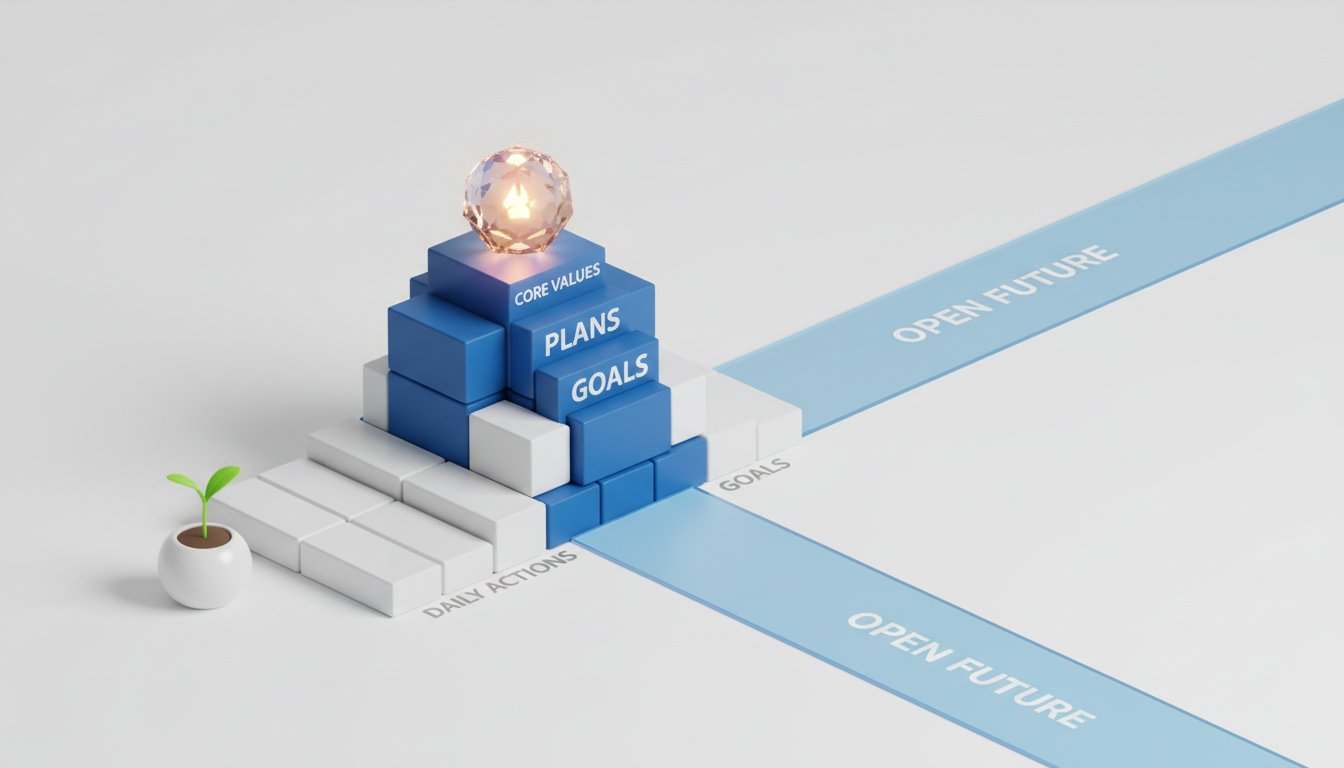

Navigating periods of intense work and potential imbalance requires a strategic approach to habit maintenance. Instead of allowing core habits like exercise, sleep, nutrition, and social connection to completely erode, establishing "minimum effective doses" for each is paramount. This means identifying the smallest, manageable commitment that keeps a habit alive, such as 20 minutes of exercise five days a week or a weekly social connection, rather than aiming for pre-disruption levels. This strategy prevents habits from dropping to zero, making it significantly easier to rebuild them once the demanding period concludes. Periodizing these intense phases and incorporating occasional "good habit" weeks or weekends can further support this maintenance. Moreover, being highly intentional about what activities are permitted during these high-demand periods is critical; less essential or time-consuming activities must be consciously excluded to preserve the limited "slack" available.

In athletic training, distinguishing between normal fatigue and chronic exhaustion is essential for sustained performance and preventing overtraining. Comparing one's recovery to others is counterproductive, as individual recoverability varies significantly based on genetics, age, and training history. Instead, athletes must establish personal norms for how workouts and recovery feel. Deviations from these established norms that linger for more than a day or two, such as an easy run feeling like a maximal effort, signal chronic fatigue that requires attention. This often involves adjusting training volume, such as reducing the number of high-intensity workouts or incorporating more variability in weekly mileage, to allow the body to better absorb accumulated load. For athletes, particularly those engaged in endurance sports, adequate carbohydrate intake is often a critical, albeit sometimes overlooked, factor in managing fatigue and recovery. Ultimately, managing fatigue relies on understanding individual responses, establishing personal norms, and making data-informed adjustments to training load, rather than adhering to generalized external standards.

The post-race recovery period presents a nuanced challenge, balancing the desire to maintain fitness with the need for genuine rest. While elite athletes might take extended breaks, most individuals benefit from a defined period of active recovery, typically one to two weeks, to allow both physical and mental restoration. Beyond this initial rest, finding a "minimum effective dose" for maintaining fitness and mental well-being is key. This might involve shorter, less intense workouts than usual or focusing on activities that feel restorative rather than taxing. The anxiety of losing fitness is a natural part of this process; however, recognizing that some decline in peak performance is inevitable and even necessary for long-term sustainability is crucial. This period is an opportunity to gather data on how the body and mind respond to different recovery protocols, informing future training cycles and ultimately contributing to a more robust, long-term approach to performance and well-being.

Action Items

- Audit personal habits: Define minimum effective doses for exercise, sleep, nutrition, and community engagement during intense work periods to prevent bad habit formation.

- Create a "boring work" framing exercise: For 3-5 key tasks, reframe tedium as a necessary process step for achieving meaningful outcomes.

- Design a "tempo run" protection system: Identify 1-2 high-focus work periods per day and implement strict boundaries to shield them from interruptions.

- Track post-race recovery deviations: For 3-5 races, document recovery duration and fitness loss to establish personal minimum effective dose for rest.

Key Quotes

"Winning achieving a goal absolutely leads to happiness you feel great you get a high you get a dopamine rush whatever neurochemical you want to call it it feels good to win those moments are wonderful we also trick ourselves we say that you got to find fulfillment in the journey but each and every one of us still wants to win and that is motivation to go and do the thing and to get the best out of yourself and to try to achieve however that happiness that you get while very real is also very ephemeral it comes and it goes you are on the medal stand for all of three minutes while they sing your country's national anthem you're on the best seller list literally for a week maybe two or three if you're lucky you get the promotion and you go out to dinner with your supervisor and then the next day you've actually got to do the work so the happiness is real it's intense but it is acute and then it's fleeting what is not acute what is not fleeting is the lasting satisfaction and the fulfillment that you get and that is what is found along the way"

Brad Stalberg argues that while achieving goals provides temporary happiness, this feeling is fleeting. He distinguishes this acute happiness from the lasting satisfaction and fulfillment derived from the process itself. Stalberg emphasizes that it is natural and beneficial to desire both the thrill of winning and the deeper contentment found in the journey.

"The best climbers they're hell bent on getting to the peaks they're meticulous about it they want it it's bad that's their version of winning and they've also internalized at the same time that they'd better find fulfillment in the actual climb itself so that's how i answer this question it's not either or it's both and you get this acute visceral but very fleeting happiness from achievement and that is not to be confused with lasting satisfaction or fulfillment that comes in the process and it's totally human and totally normal to want both those things"

Brad Stalberg uses the metaphor of mountain climbing to illustrate the dual pursuit of achievement and process fulfillment. He explains that climbers are driven to reach the summit (winning) but also find satisfaction in the act of climbing itself. Stalberg concludes that it is not a matter of choosing one over the other, but rather embracing both the fleeting joy of accomplishment and the enduring contentment of the journey.

"So i think you can see it it's almost like the expectations and the framing matters a lot is if we go into the thing and say oh this is so boring like i have to enter things on this spreadsheet again and again and again or you see it as like this is just part of the process this is like doing the stupid ab exercises the warm up drills the other things that i don't like about running that much but they're required to get like to get the most out of myself and something that i'm meaningfully pursuing"

Steve Magnus suggests that framing and expectations significantly influence how one perceives tedious work. Magnus argues that viewing mundane tasks as an integral part of a meaningful process, rather than as inherently boring, can lead to fulfillment. He likens this to athletes accepting necessary but unenjoyable warm-up drills as essential for achieving their goals.

"The key is not to let it go down to zero to define what's going to allow you to stay in touch with the thing while also having a chance to attain that that new adjusted goal and then once that season of craziness ends you go back to what it's like before it's always easier to maintain than to build it's a universal principle that's that endurance training 101 and it applies to life"

Brad Stalberg advises on managing periods of intense work by maintaining "minimum effective doses" of core life areas like exercise, sleep, community, and nutrition. Stalberg emphasizes that the goal is not to eliminate these habits entirely but to scale them down to a manageable level. He states that this approach prevents complete habit breakdown and makes it easier to return to previous levels once the demanding period concludes, drawing a parallel to endurance training principles.

"So you just have to acknowledge that and not try to mimic something else if this is a change right where you're like oh i used to recover really well and now i'm doing the same things and not not bouncing back then that means you need to look at everything outside of that you're looking at you know a are you getting older b are you supporting your body nutritionally with food recovery sleep all the things that we've talked about in previous podcasts are you doing all those things and if not maybe that's the weak link"

Steve Magnus addresses chronic fatigue by advising individuals to stop comparing their recovery to others and to acknowledge their unique physiological responses. Magnus suggests that if a change occurs where one no longer recovers well from previously manageable stressors, it's crucial to examine external factors. These factors include age, nutrition, sleep, and overall recovery practices, indicating that the issue may lie outside the training itself.

"The key is you're just not digging that hole again yeah i try to think of it as like i'm running an experiment and everything is just collecting data and trying to use that data to then inform my new hypothesis because there are no there are no we've sort of echoed a few times here there are no easy broadly applicable universal answers and not even just from person to person but from race to race right like some races you're going to bounce back more quickly than others and uh others is going to take more time and it's just like observing your body and observing where you're at observing how you're feeling and i think trying to make the best um guesses and estimates off of that but that also requires experience and doing it right"

Clay Skipper discusses managing post-race recovery by viewing the process as an ongoing experiment. Skipper emphasizes that there are no universal answers, and what works can vary significantly between individuals and even between different races for the same person. He advocates for observing one's body, collecting data, and using that information to form hypotheses for future recovery strategies, highlighting the importance of experience in developing this intuition.

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "The Way of Excellence" by Brad - Mentioned as a pre-orderable book with a quote from Steve Kerr.

Articles & Papers

- AI-generated, unedited transcript - Provided as a link for listeners.

Websites & Online Resources

- The Growth Equation newsletter - Referenced for subscription.

- The Growth Equation Academy - Mentioned as a community to join.

- acast.com/privacy - Provided for information regarding hosting.

Podcasts & Audio

- excellence, actually - The podcast where the episode is featured.

- The Growth Equation podcast - Mentioned as a platform on iTunes and Apple Podcasts.

Other Resources

- The Arrival Fallacy - Discussed as a concept related to achievement and fulfillment.

- Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) - Mentioned as a metric for measuring fatigue in training.