Mispredicting Happiness--Hedonic Adaptation and Social Connection's Role

The science of happiness reveals that our pursuit of joy is often misguided, leading us to chase elusive milestones while overlooking the immediate, actionable strategies that truly foster well-being. This conversation with Yale Psychology Professor Laurie Santos unpacks the cognitive biases that warp our predictions about what will make us happy, highlighting how the "arrival fallacy" and hedonic adaptation conspire to diminish the impact of our achievements and setbacks. The hidden consequence? We perpetually defer our own happiness, becoming less resilient and less capable of contributing positively to the world. This analysis is crucial for anyone seeking genuine, lasting contentment and a more effective approach to personal growth and societal contribution, offering a scientific framework to reorient our focus from future fantasies to present-day realities.

The Arrival Fallacy: Why Your Future Self Won't Be as Happy as You Think

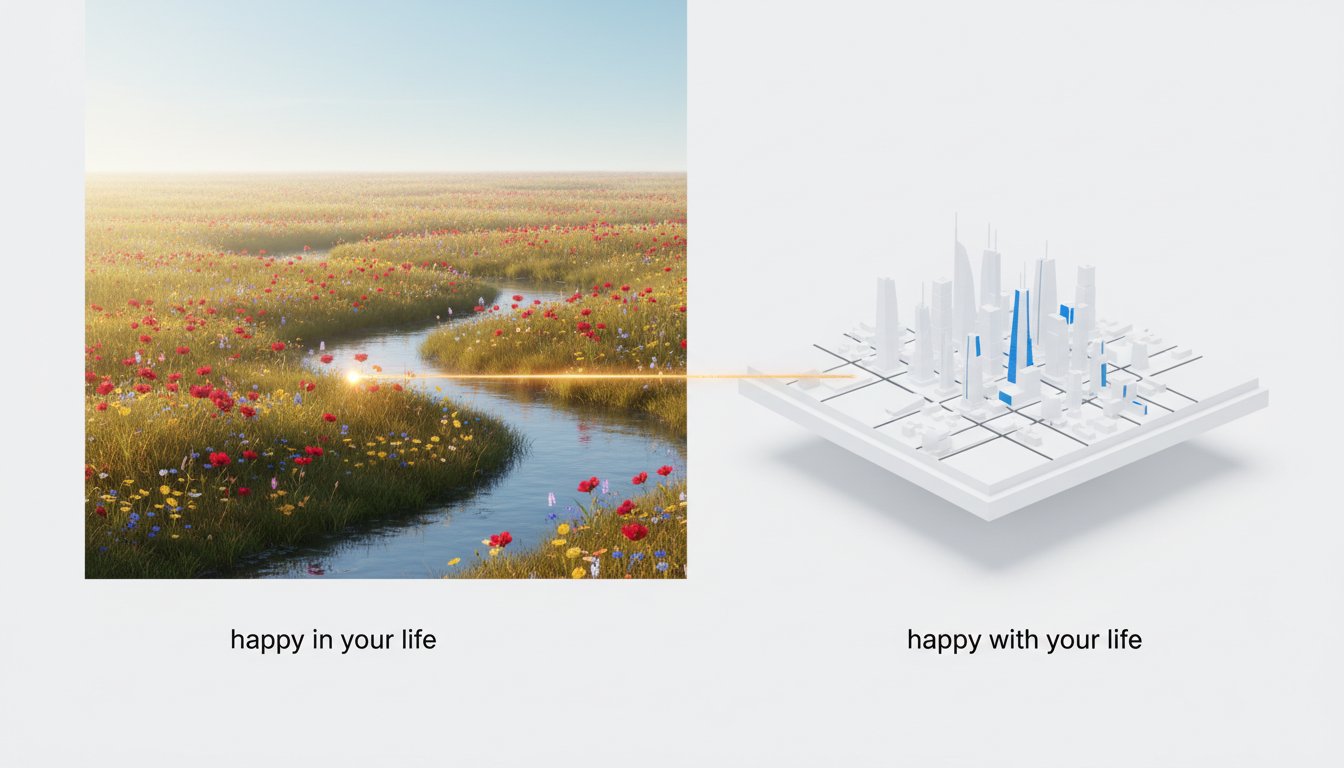

We are, by nature, optimists about our future happiness. We envision a future state where achieving a specific goal--a promotion, a new relationship, a significant milestone--will unlock a perpetual state of bliss. This pervasive belief, termed the "arrival fallacy" by researchers, is a fundamental miscalculation of how our minds work. Laurie Santos, a leading expert in happiness research, explains that this fallacy leads us to "stall our happiness in present day with the hope that this future event will deliver all the goods." The reality, however, is that these anticipated moments of elation rarely live up to our inflated expectations, and their impact is far more fleeting than we predict.

This misprediction isn't limited to positive events. We also dramatically overestimate the negative impact of adverse circumstances. Santos highlights research showing that our "impact bias is worse in the negative direction than it is in the positive direction." This means we dread future hardships far more than is warranted, underestimating our inherent resilience. This phenomenon, known as hedonic adaptation, suggests that humans possess a remarkable capacity to return to their baseline happiness levels, regardless of significant positive or negative life events. While this might sound disheartening--implying that neither achievements nor setbacks will alter our happiness trajectory as much as we imagine--it offers a powerful psychological buffer. Understanding that we are more resilient than we believe can liberate us from excessive worry about future failures and allow us to approach life with greater openness and less fear.

"The arrival fallacy, right? Or I like to call it the happily ever after fallacy. Like this thing happens and I'll be happy ever after, right?"

-- Laurie Santos

The implications of this are profound. If we consistently misjudge what will bring us joy and how long it will last, our entire strategy for pursuing happiness is likely flawed. We invest immense energy chasing external achievements, believing they are the keys to contentment, while neglecting the more sustainable, internal drivers of well-being. This leads to a perpetual state of anticipation, where true happiness is always just over the horizon, perpetually out of reach. The downstream effect is a population that is stressed, anxious, and less capable of experiencing genuine joy in the present moment.

The Hedonic Treadmill: Why Your Set Point is More Stubborn Than You Think

The concept of hedonic adaptation, or the "hedonic treadmill," suggests that our happiness levels tend to revert to a stable baseline, much like a treadmill returning to its default setting. This means that major life events, whether positive like winning the lottery or negative like experiencing a severe injury, have a less enduring impact on our overall happiness than we anticipate. Santos explains that "we just kind of go back to wherever your set point was in happiness, no matter what the good stuff and the bad stuff is." This isn't necessarily a cause for despair. Instead, it's a testament to human resilience.

However, the cognitive biases associated with these predictions don't disappear simply because we understand them. Santos notes, "even when we learn how they work, they don't go away." We continue to make the same misjudgments about future events. The advantage of understanding hedonic adaptation, then, lies not in eliminating the bias, but in developing a greater awareness. This awareness can help us "course correct a little bit after the fact," mitigating the emotional fallout of our mispredictions. It allows us to recognize that our current distress over a potential setback is likely an exaggeration, and that our capacity to adapt is greater than we perceive.

The failure to grasp this concept leads many to chase external circumstances, believing they will fundamentally alter their happiness. This is where conventional wisdom fails: it often equates happiness with achievement and acquisition. The reality is that focusing on the "arrival"--the promotion, the new house--is a less effective strategy than cultivating internal states and behaviors that promote well-being consistently. The competitive advantage here lies not in achieving more, but in understanding the limits of external change and focusing on the internal levers of happiness.

The Power of Reference Points: Silver Medals and Bronze-Clad Elation

Our perception of happiness is not an objective measure; it's deeply influenced by our reference points--the benchmarks against which we compare our current situation. Laurie Santos uses the compelling example of Olympic medalists to illustrate this phenomenon. A silver medalist, having narrowly missed the gold, often experiences profound disappointment. Their reference point is the gold medal, and the feeling of "not as good as I could have done" overshadows the immense achievement of being second-best in the world. Their emotional expressions, Santos observes, can appear as "contempt, disgust, like deep sadness."

Conversely, a bronze medalist, who might have been further from gold, often displays elation. Their salient reference point is not winning gold, but the possibility of winning no medal at all. Their success, therefore, is framed by the avoidance of failure, leading to a feeling of immense gratitude and triumph. This demonstrates that our emotional response is less about the objective outcome and more about the subjective comparison.

"What's going on is that they're evaluating based on an expectation, a reference point. What's the obvious reference point if you've won silver? It's the gold medal. You didn't get that."

-- Laurie Santos

This principle has significant implications for our daily lives. We often set our expectations based on idealized scenarios or the achievements of others, leading to dissatisfaction with our own accomplishments. By consciously adjusting our reference points--focusing on progress rather than perfection, celebrating small wins, and acknowledging how far we've come--we can significantly enhance our subjective experience of happiness. This requires a deliberate shift in perspective, moving away from comparing ourselves to an unattainable ideal and towards appreciating our current reality. The delayed payoff of this mental reframing is a more consistent and less volatile sense of well-being, creating a durable advantage over those who are perpetually chasing an ever-receding finish line.

The Unexpected Architects of Joy: Social Connection and Time Affluence

Beyond reframing our expectations, scientific research points to two critical, often undervalued, pillars of happiness: robust social connections and a subjective sense of having enough time, or "time affluence." Santos emphasizes that social connection is a "necessary condition for high happiness." We are, by our nature as social primates, wired to derive joy and satisfaction from our interactions with others. This holds true for both introverts and extroverts; while introverts may need periods of solitude, they still benefit immensely from meaningful social engagement, particularly in smaller, more intimate settings. The "leaky tire" analogy, proposed by researcher Nick Epley, suggests that brief, positive interactions with strangers, like a chat with a barista, act as quick ways to "fill up your leaky tire" of happiness.

The challenge, however, is that modern life, particularly the ubiquity of smartphones, presents a significant opportunity cost to these vital connections. Phones, designed for communication, have become conduits for endless distraction, pulling us away from present, real-life interactions. Catherine Price's "WWW" framework--What for, Why now, What else--offers a mindful approach to phone usage, prompting us to consider the purpose, the emotional trigger, and the opportunity cost of picking up our device.

Similarly, "time famine"--the subjective feeling of lacking time--is detrimental to well-being, mirroring the physiological stress of actual hunger. Researcher Ashley Whillans suggests that we can cultivate "time affluence" by strategically spending money to buy back time, whether through outsourcing chores or choosing services that save us time. Furthermore, we can harness "time confetti"--those small, fragmented moments throughout the day--for intentional activities like calling a friend or practicing mindfulness. These strategies, while requiring conscious effort, build a foundation for lasting happiness that external achievements alone cannot provide. The competitive advantage lies in prioritizing these fundamental human needs over the often-illusory pursuit of external validation.

"We really get lots of positive emotion out of being with other people. We feel like our life is more satisfying when we're close to others."

-- Laurie Santos

Key Action Items

- Reframe Expectations Daily: Consciously identify and adjust your reference points. Instead of focusing on what you haven't achieved, acknowledge and appreciate what you have accomplished, however small. Immediate Action.

- Prioritize Social Connection: Schedule regular, intentional time for meaningful interactions with loved ones. This includes phone calls, in-person meetings, and even brief, positive exchanges with acquaintances. Immediate Action, reinforcing over the next quarter.

- Mindful Technology Use: Implement the "WWW" (What for, Why now, What else) framework when reaching for your phone to reduce distraction and reclaim present-moment awareness. Immediate Action.

- Invest in Time Affluence: Identify one recurring task that consumes significant time and explore options for outsourcing or streamlining it, even if it requires a small financial outlay. Over the next quarter.

- Harness Time Confetti: Designate specific, small blocks of "time confetti" (5-15 minute windows) for intentional well-being practices, such as calling a friend, brief meditation, or journaling. Immediate Action, ongoing.

- Embrace Discomfort for Growth: Recognize that discomfort in social interactions or in letting go of external validation is often a precursor to genuine happiness and resilience. Longer-term investment, paying off in 6-12 months.

- Challenge the Arrival Fallacy: When anticipating a future event, consciously predict its impact on your happiness and then deliberately temper those predictions, acknowledging the role of hedonic adaptation. Ongoing practice, strategic review quarterly.