The Hidden Power of Doubt: Why Hesitation Can Be Your Greatest Asset

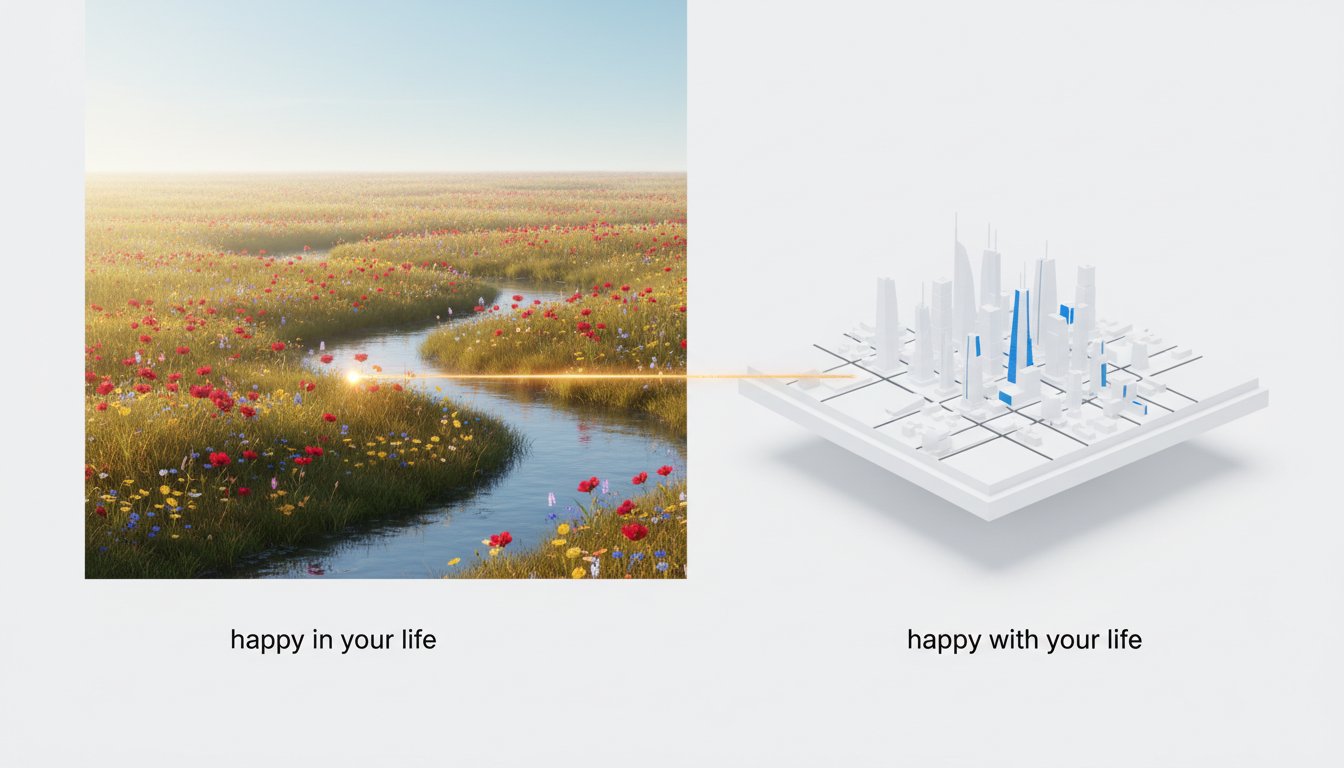

This conversation with researcher Bobby Parmar reveals a counterintuitive truth: doubt, often perceived as a weakness, is actually a critical tool for better decision-making, stronger relationships, and navigating complexity. The non-obvious implication is that our ingrained drive for certainty can actively hinder growth and lead us astray. Those who embrace doubt, not as indecision but as an active process of inquiry, gain a significant advantage in a world awash in ambiguity. This insight is crucial for leaders, strategists, and anyone seeking to make more robust choices in both personal and professional life, offering them a framework to move beyond superficial confidence to a deeper, more resilient form of understanding.

The Peril of Certainty: Why Our Brains Resist Doubt

Our instinct is to equate strong leadership with unwavering confidence and decisive action. We admire leaders who seem to have all the answers, projecting an image of certainty that can be reassuring in uncertain times. However, as Bobby Parmar explains, this very confidence can be a double-edged sword. Overconfidence can blind us to risks, decisiveness can stifle dissent, and determination can morph into stubbornness. Parmar’s research highlights how our brains are wired to seek certainty, often viewing doubt as an aversive state. This drive stems from interconnected neural systems: the "pursue system" (reward-driven approach), the "protect system" (threat avoidance), and the crucial "pause and piece together system" which is responsible for processing uncertainty. When faced with ambiguity, the protect system often overrides the more nuanced pause system, pushing us towards quick, often suboptimal, decisions to alleviate discomfort.

"When we're in school, we learn that being smart means getting the right answer. People like to be what I call right answer getters. Certainty makes us feel really great, right? It feels like we have agency and we have control over our lives. But there are also some serious downsides to certainty. It can make us really overconfident. It can get us to ignore competing perspectives. We can underestimate risks."

This aversion to uncertainty is deeply ingrained. Our brains associate the "me" with "good," making any critique feel like a personal attack. This intertwining of self and value, as psychologist Emily Falk elaborates, can lead us to hold tightly to past decisions or beliefs, even when evidence suggests otherwise. When we receive feedback, especially unsolicited advice, our protect system can kick in, not just to defend our actions, but to defend our very sense of self. This is further exacerbated by the fundamental attribution error, where we attribute our own mistakes to external circumstances but others' mistakes to their inherent character flaws. In high-stakes situations, like a military command or a business strategy meeting, this tendency can lead to catastrophic misjudgments, as teams prioritize appearing decisive over being accurate.

The "Pre-Mortem" Advantage: Embracing Doubt as a Strategic Tool

The key to navigating this cognitive trap lies in actively engaging with doubt, rather than suppressing it. Parmar advocates for treating intuition not as a final decision, but as a hypothesis to be tested. This requires a conscious shift from being "right answer getters" to "better answer makers." Expert decision-makers, whether they are generals, entrepreneurs, or seasoned nurses, don't necessarily arrive at conclusions faster; rather, they invest more time in understanding the problem space, collecting data, and considering multiple perspectives. They are more sensitive to their surroundings, actively looking for "anomalies"--early signals that something is departing from expectations. This practice, which Parmar calls "anomalizing," is essentially asking, "How can I be wrong?"

A powerful application of this principle is the "pre-mortem." Instead of planning for success, a pre-mortem involves imagining a project or decision has failed spectacularly and then working backward to identify the most likely causes of that failure. This forces a deep dive into potential pitfalls, second and third-order consequences, and unintended outcomes that might be overlooked in a purely optimistic planning phase. This proactive examination of potential failures builds resilience and adaptability, creating a strategic advantage that conventional, confidence-driven approaches often miss.

"One of the things that we work with with my students is not to ignore our intuition, but to take that intuition as a starting point. One big challenge when it comes to judging our intuitions is that when we go out and test our intuitions, we often have a propensity to find evidence that matches our intuition."

The military study on captains versus generals illustrates this vividly. While novices treated their intuition as a decision and sought data to confirm it, experts treated their intuition as a hypothesis, generating questions about key uncertainties and building flexible strategies with mitigation plans. This methodical engagement with doubt, even when uncomfortable, leads to more robust and adaptable outcomes. It’s this willingness to sit with uncertainty, to explore the "what ifs" and "how could we be wrong," that separates effective decision-making from mere action.

Actionable Strategies for Cultivating Productive Doubt

The insights from this conversation offer a powerful toolkit for anyone looking to improve their decision-making and interpersonal interactions. By consciously practicing these strategies, individuals and teams can transform doubt from a source of anxiety into a catalyst for growth and strategic advantage.

- Embrace the "Pre-Mortem": Before launching a project or making a significant decision, convene a session to imagine its failure. Identify the most probable reasons for this failure and proactively develop mitigation strategies. This pays off in 12-18 months by preventing costly mistakes.

- Practice "Anomalizing": Actively look for early, weak signals that deviate from your expectations. When something feels "off," don't dismiss it; investigate it. Implement this daily to build observational skills.

- Reframe Intuition as Hypothesis: Treat your gut feelings as starting points for inquiry, not as final answers. Ask yourself, "What evidence would make me change my mind?" This is a continuous practice, essential for learning.

- Cultivate Psychological Distance: When receiving feedback, create space between your sense of self and the critique. Use techniques like imagining yourself two years in the future or adopting the perspective of a wise role model. Practice this during challenging conversations.

- Use Storytelling for Feedback: When giving feedback, consider framing it within a narrative. Stories can bypass defensiveness and allow for deeper processing of information. Integrate this into team communication over the next quarter.

- Seek "Hopeful Skepticism": Be open to feedback but demand evidence. Ask clarifying questions about motivations and compatibility with your goals, rather than immediately accepting or rejecting input. Apply this in all feedback interactions.

- Invest in "Better Answer Making": Recognize that expertise involves a commitment to continuous learning and refinement, not just having the right answers. Prioritize understanding the problem over quickly finding a solution. This is a long-term investment in personal and professional development.