Experimental Archaeology Reveals Ancient Ingenuity and Modern Relevance

TL;DR

- Experimental archaeology, by recreating ancient technologies like Viking-era wound salves, reveals that common ingredients such as onion, garlic, and wine, when combined with ox gall and copper, effectively combat modern drug-resistant bacteria and biofilms.

- The Tuli people's unique, unfired pottery, glazed with seal oil and blood, demonstrates advanced chemical understanding for survival, enabling heat conduction and water sealing in a wood-scarce, damp Arctic environment.

- Traditional archaeology's focus on excavation is complemented by experimental approaches, which, despite initial resistance from some academics, offer active, engaging methods to understand past human behaviors and technologies.

- Ancient surgical survival rates, particularly for trepanation, were higher in regions like Papua New Guinea than in 19th-century London due to a lack of understanding of germ theory and inconsistent hygiene practices in established hospitals.

- Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), developed through decades of research, represent a significant breakthrough in molecular architecture, enabling highly porous structures capable of capturing CO2, extracting metals, and trapping water.

- Linguistic analysis of Taylor Swift's interviews over time reveals how vowel pronunciation shifts can reflect dialectal influences and conscious community affiliation, demonstrating a quantifiable link between speech and social integration.

Deep Dive

Experimental archaeology, by recreating ancient technologies, food, and medicine, offers a dynamic and engaging lens into human history, revealing practical ingenuity and challenging traditional archaeological methods. This approach reveals how ancient peoples, facing harsh environments and limited resources, developed sophisticated solutions, such as the Tuli people's unique pottery, which, though simple in appearance, was highly effective for their survival needs. The practice also highlights the enduring relevance of historical knowledge, as demonstrated by the rediscovery of an ancient salve's efficacy against drug-resistant bacteria, suggesting that the past holds valuable lessons for contemporary challenges.

The field of experimental archaeology, as explored through Sam Kean's research, moves beyond passive excavation to active reconstruction, allowing practitioners and enthusiasts alike to engage directly with the material culture of the past. This hands-on engagement transforms abstract historical data into tangible experiences, fostering a deeper appreciation for the labor and skill involved in ancient technologies. For instance, recreating Tuli pottery, which lacked the typical features of fired, large-walled vessels, required understanding the constraints of their environment, such as a lack of wood for firing and the need for small, unfired pots. The Tuli people's solution of using seal oil and blood as a glaze and sealant, respectively, demonstrates a practical, albeit unconventional, mastery of chemistry to overcome these limitations, enabling them to boil water effectively in their challenging climate.

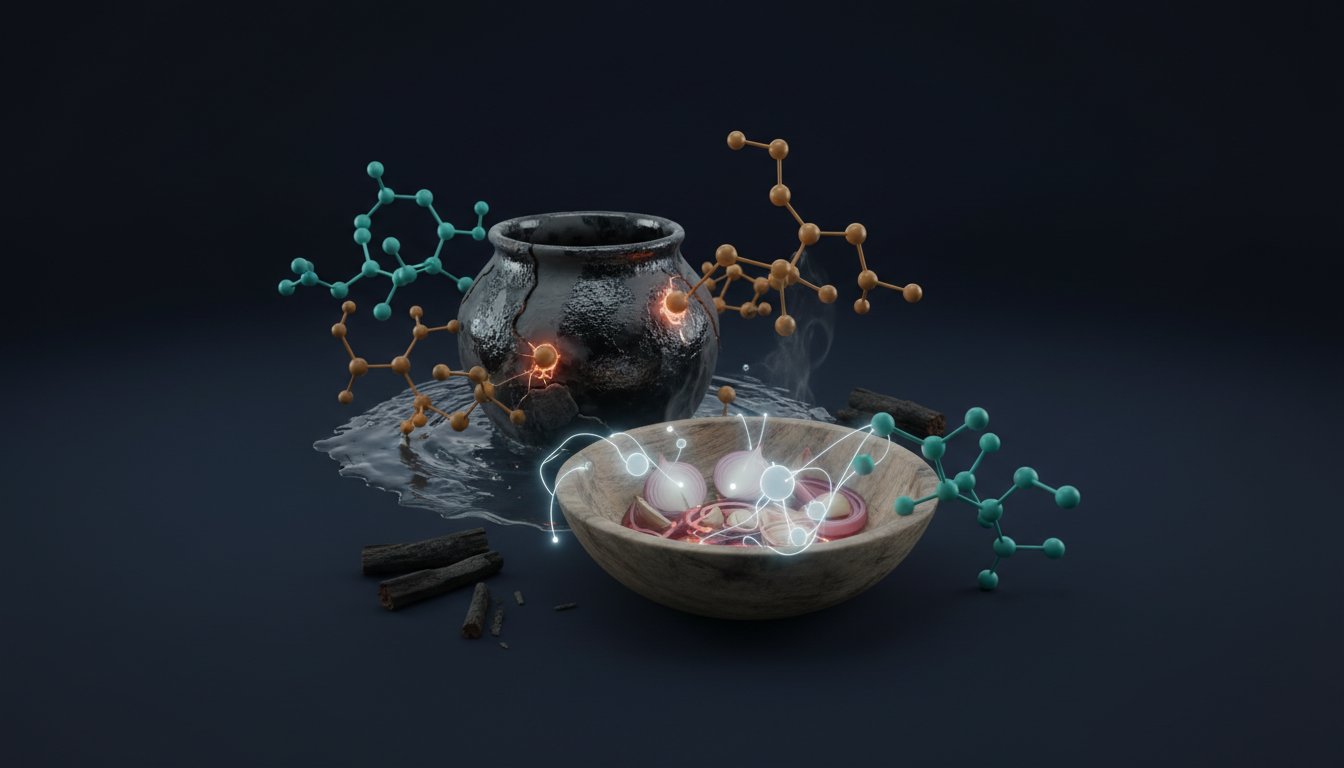

Furthermore, experimental archaeology has shown that historical practices can sometimes outperform modern ones due to a better understanding of fundamental principles, such as hygiene. The survival rates of ancient trepanation surgeries, particularly in regions like Papua New Guinea where wounds were cleaned with coconut milk, exceeded those in 19th-century London hospitals, where germ theory was not yet widely understood. This discrepancy underscores how attention to basic cleanliness, even without modern scientific knowledge, could yield superior medical outcomes. The practice also reveals that historical innovations often arose from necessity, as seen with the Viking-era wound salve, which combined common ingredients like onion, garlic, and wine, ultimately proving effective against modern drug-resistant bacteria and biofilms. This suggests that ancient cultures possessed a practical, empirical understanding of chemistry and biology that is only now being fully appreciated and validated by scientific study.

The book also touches upon the development of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as a modern scientific advancement, highlighting the continuous evolution of materials science. These highly porous structures, developed by scientists like Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar Yaghi, have immense surface area and can be designed for specific applications, such as capturing carbon dioxide or extracting metals from wastewater. This contemporary example of molecular architecture complements the historical explorations by showcasing how human ingenuity, whether ancient or modern, seeks to manipulate materials to solve pressing problems, from survival in harsh climates to environmental remediation.

Ultimately, experimental archaeology provides a powerful bridge to the past, demonstrating that our ancestors were not simply passive recipients of their circumstances but active innovators who developed ingenious solutions to complex problems. The process of recreating their technologies, medicines, and foods offers not only a richer understanding of their daily lives but also a valuable perspective on human resilience, resourcefulness, and the scientific principles that underpin even the most basic of human endeavors.

Action Items

- Create experimental archaeology framework: Document 5 key steps for recreating historical recipes, tools, or technologies to ensure reproducibility and learning.

- Audit ancient wound salve recipe: Test efficacy against 3 common drug-resistant bacteria strains (e.g., MRSA, VRE) and analyze biofilm disruption potential.

- Design pottery firing simulation: Model the impact of Alaskan dampness and limited wood fuel on unfired clay pottery to understand structural integrity challenges.

- Measure historical surgical survival rates: Compare trepanation survival rates between pre-germ theory urban centers and remote communities using available archaeological data.

Key Quotes

"I was just really excited to try it I was just really curious about whether it would have an effect whether it would actually help um I was a little apprehensive because it was really really pungent I mean it just it was raw onion raw garlic it really had a very strong smell and the white wine I used especially it had turned sort of this neon color uh I think it was the copper leaching off the pennies that I had used and uh it looked sort of like the statue of liberty green you know onion and garlic and wine sounds like the start of a great dinner pennies on the other hand haven't seen that in a lot of recipes but Sam was trying out this concoction for science and also to recreate some history."

Sam Keen describes his personal experience testing an ancient wound remedy, highlighting the sensory aspects and his initial curiosity mixed with apprehension. Keen's willingness to experiment with a pungent, unconventional mixture underscores the experimental approach to understanding historical practices. This quote sets the stage for how experimental archaeology can involve direct, hands-on testing of historical recipes.

"The goal of experimental archaeology is to recreate things from the past uh sometimes that is ancient foods you know recreating lost recipes sometimes it's making ancient stone tools or weapons sometimes it's doing something big like building a boat and sort of taking off and uh sailing like they would have thousands of years ago and it got me excited because it was a new way of doing and looking at archaeology much more active and much more engaging."

This quote defines the core purpose of experimental archaeology, as explained by Sam Keen. Keen emphasizes that this field goes beyond traditional excavation by actively recreating ancient technologies and practices. He expresses his personal excitement for this approach, finding it more dynamic and engaging than conventional archaeological methods.

"Sure there were those virgin bathwater recipes that should probably be disregarded but there was also a recipe that might have some merit to it the recipe called for mixing onion garlic ox gall so bile from the liver of an ox and wine in a copper bowl you let it steep for nine days and then you use that on styes so infections uh of the eye and they looked at them and they thought well you know wine has alcohol in it it's kind of antiseptic onion and garlic those can be antiseptic too so there's a shot that this one might work."

This passage, recounted by Sam Keen, details the discovery and initial assessment of a specific recipe from Bald's Leechbook by Christina Lee and Freya Harrison. Keen highlights how the researchers identified a potentially effective ancient remedy amidst less credible ones. The interpretation focuses on the scientific reasoning applied to an ancient text, noting the antiseptic properties of common ingredients like wine, onion, and garlic.

"The pots were so simple that they deceived a ceramics archaeologist at the university of nevada las vegas named Karen Harry who Sam talked to for his book and she had a colleague Liam Frank who came to her and Liam worked in upper alaska and he came to her with the remains of some cooking pots and he said well take a look at these what do you think about these and Harry actually did not believe that they were cooking pots she said no there's no chance these are cooking pots these look nothing like traditional cooking pots and then r Kelly said well you know they were found near a fire and we know that they were cooking pots so Harry kind of had to swallow her pride a little bit and say okay I got to figure this mystery out I got to understand what was going on here."

Sam Keen shares an anecdote about how the simplicity of Tuli people's pottery initially misled a ceramics archaeologist. Keen illustrates how preconceived notions based on traditional pottery characteristics can obscure the reality of ancient technologies. This story demonstrates the challenges and surprises encountered in experimental archaeology when artifacts do not fit expected patterns.

"The oil is basically conducting heat from the fire into the contents of the pot and helping the water boil the seal blood essentially sealed uh sealed off the outside of the pot so that the water inside it wouldn't seep into the walls and destroy them as gross as it is to imagine glazing pottery with blood Tuli pottery is such a cool example of how ancient people figured out chemistry that helped them survive extreme conditions."

Sam Keen explains the dual function of seal oil and seal blood in Tuli pottery, revealing an ancient application of chemical principles. Keen highlights how these ingredients served distinct purposes: oil for heat conduction and blood for sealing the porous clay. This quote showcases how experimental archaeology can uncover sophisticated, survival-driven chemical knowledge in ancient cultures.

"Obviously new life in the past was harder in a lot of ways it took a lot more work to uh get clothing uh to make food you know even to get uh a meal took a lot more work but it's hard to appreciate just how difficult it was until you actually go through the steps and do it we live in a culture I think that we have a lot of disposable things yet we buy something and if you just buy it from a store you're not really invested in it in the same way when you make something you care about it a lot more you've put some of yourself into that thing so I got kind of attached to the tools and the things that I made I really cared about them in some way just because I had put some of myself in it so that connection I felt with inanimate objects was not something I expected before but it was uh was a nice little surprise."

Sam Keen reflects on the personal impact of engaging in experimental archaeology, contrasting the past with modern convenience. Keen emphasizes that direct experience with historical tasks reveals the immense effort required for basic survival. He also notes an unexpected emotional connection formed with the tools and objects created through his own labor, a sentiment often absent in a culture of disposable goods.

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "Dinner with King Tut" by Sam Kean - Mentioned as the subject of the episode and the source of many of the experimental archaeology examples discussed.

- "The Disappearing Spoon" by Sam Kean - Mentioned as one of the author's previous science books.

- "The Ice Pick Surgeon" by Sam Kean - Mentioned as one of the author's previous science books.

Articles & Papers

- "Bald's Leechbook" (European text) - Referenced as an ancient manuscript containing recipes for medicines, including one for eye infections that was studied for its potential efficacy.

- "Journal of the Acoustical Society of America" - Mentioned as the publication where a study on Taylor Swift's changing vocal patterns was published.

People

- Sam Kean - Author of "Dinner with King Tut," guest on the podcast, and practitioner of experimental archaeology.

- Sam Jones - Co-host of Tiny Matters.

- Deboki Chakravarti - Co-host of Tiny Matters.

- Christina Lee - Professor of Viking Studies at the University of Nottingham, who studied "Bald's Leechbook."

- Freya Harrison - Microbiologist at the University of Nottingham, who studied "Bald's Leechbook" and tested its ancient salve.

- Karen Harry - Ceramics archaeologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who studied Tuli pottery.

- Liam Frank - Colleague of Karen Harry who worked in upper Alaska and brought her Tuli pottery remains.

- Susumu Kitagawa - Awardee of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

- Richard Robson - Awardee of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

- Omar Yaghi - Awardee of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

- David Anderson - Host of the podcast "Inflection Point."

- Gina Vitale - Host of the podcast "Inflection Point."

- Taylor Swift - Subject of a study on vocal pattern changes over her career.

Organizations & Institutions

- Tiny Matters - Science podcast about the little things that have a big impact.

- American Chemical Society (ACS) - Science nonprofit that produces the Tiny Matters podcast.

- University of Nottingham - Institution where professors Christina Lee and Freya Harrison studied "Bald's Leechbook."

- University of Nevada, Las Vegas - Institution where archaeologist Karen Harry studied Tuli pottery.

- Chemical & Engineering News (C&EN) - Source for the science history podcast "Inflection Point."

- Multitude - Producer of the Tiny Matters podcast.

Podcasts & Audio

- Tiny Matters - Science podcast about the little things that have a big impact.

- Inflection Point - Science history podcast from Chemical & Engineering News.

- Cool Stuff Daily - Podcast that looks at science, tech, and "wait what" stories.

Other Resources

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) - Molecular architecture developed by Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar Yaghi, recognized with the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, known for their extreme porosity and applications in capturing and storing substances.

- Experimental Archaeology - A field that aims to recreate past technologies, foods, and practices to better understand history.

- Viking Conquest Era - Period around the year 1000 when the recipe for wound treatment was documented.

- Tuli People - Indigenous group who settled in northern Alaska by the year 1000, known for their advanced hunting tools and unique pottery.

- Germ Theory - Concept related to understanding how infections spread, influencing survival rates in historical surgeries.

- Trepanation - A surgical procedure involving the removal of parts of the skull, practiced for thousands of years.

- Pfas - Chemicals discussed on Tiny Matters, mentioned in relation to MOFs' ability to remove them from water.