This conversation reveals the profound, often overlooked consequences of a leader's transactional foreign policy, particularly when it clashes with established international norms and alliances. President Trump's pursuit of Greenland, framed as a national security imperative, exposes a deeper systemic tension: the clash between a desire for tangible assets and the complex, long-term investments required to manage them. The non-obvious implication is that acquiring a territory is vastly different from integrating and benefiting from it, especially when the existing inhabitants have their own perspectives and the incumbent power (Denmark) provides substantial, ongoing subsidies. This analysis is crucial for policymakers, diplomats, and business strategists who navigate the shifting geopolitical landscape, offering a critical lens to identify the hidden costs and potential strategic disadvantages of aggressive, asset-focused acquisition strategies. It highlights how understanding the "money pit" aspect of governance, rather than just the "gold mine" potential, is key to sustainable advantage.

The Greenland Gambit: Unpacking the Hidden Costs of Transactional Diplomacy

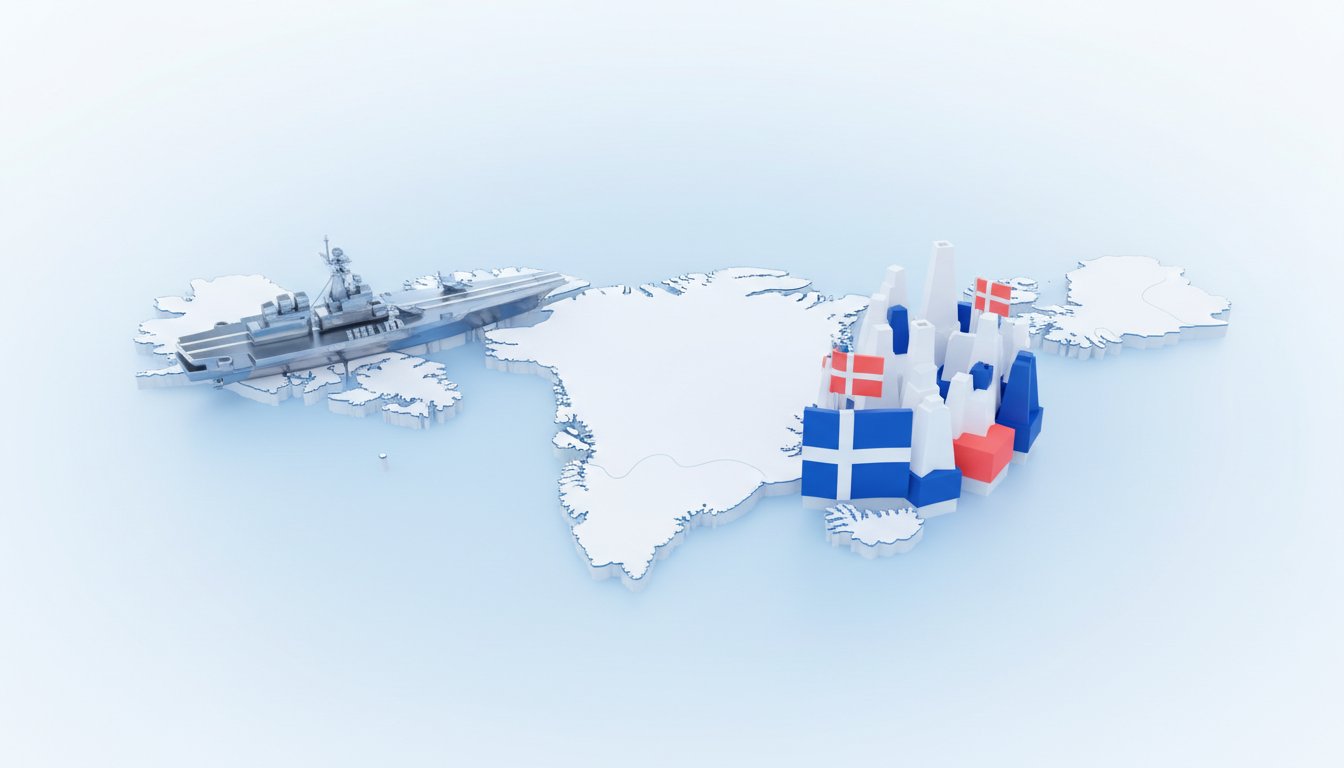

The notion of President Trump seeking to purchase Greenland, a vast, ice-covered territory controlled by Denmark, initially appears as a bold, albeit eccentric, geopolitical maneuver. However, a deeper analysis, as explored in this podcast, reveals a cascade of consequences that extend far beyond a simple real estate transaction. This isn't merely about acquiring land; it's about understanding the intricate web of economic, political, and social systems that underpin such a move, and how a transactional mindset can lead to significant downstream complications. The conversation highlights how immediate desires can blind leaders to the long-term investments and inherent complexities of governance, creating a strategic disadvantage where a competitive edge was sought.

The Mirage of the "Gold Mine"

Trump's rationale for acquiring Greenland is rooted in national security and the potential for resource extraction, particularly rare earth minerals crucial for advanced technologies. He posits that Denmark, and by extension the EU, lacks the financial capacity to adequately defend or exploit the island's resources, implying that US stewardship would be more effective and profitable. This perspective, however, critically overlooks the substantial economic reality on the ground. Max Colchester's reporting from Greenland paints a starkly different picture. The island's economy is small, heavily reliant on fishing and, crucially, Danish subsidies. The Danish government provides approximately a billion dollars annually to support Greenland's education, healthcare, and defense. This isn't a nascent economic powerhouse waiting to be unlocked; it's a territory that, by its current economic structure, functions as a significant financial commitment, a "money pit" rather than an immediate "gold mine."

"When you get there, you realize that although it's been painted as this potential El Dorado for minerals and whatnot, when you get there, you realize people basically live off fishing and Danish subsidies, and it's not a gold mine in that sense. It's more of a money pit."

This insight is critical. The immediate appeal of Greenland's mineral wealth distracts from the immense cost and logistical challenges of extraction. Building mines, roads, housing, and ports in an icy, sparsely populated environment, coupled with harsh weather conditions, represents a massive, long-term capital investment with uncertain returns. Conventional wisdom, focused on the potential upside of resources, fails to account for the systemic integration costs and the ongoing operational expenses. For a leader focused on immediate gains, the prospect of inheriting a territory that requires substantial, continuous federal funding--potentially more per capita than Alaska or Washington D.C.--is a significant deterrent that is often minimized in the pursuit of grander visions.

Escalation and the Erosion of Alliances

Trump's approach to securing Greenland quickly moved from overtures to aggressive economic coercion. When Denmark and the EU resisted, the response was a threat of significant tariffs on European goods, escalating from 10% to 25% if Greenland was not ceded. This transactional escalation strategy, while potentially effective in forcing concessions in a business deal, has profound negative consequences for geopolitical alliances. European leaders, like French President Macron, expressed bewilderment, highlighting the dissonance between this aggressive stance and the established norms of transatlantic cooperation.

The EU's potential response, utilizing its Anti-Coercion Instrument, demonstrates a system designed to counter such economic blackmail. However, the podcast underscores the inherent risks. Retaliation could trigger further escalation, and many EU members would likely lobby against stringent measures due to fears of blowback on their own economies. This creates a feedback loop where aggressive demands lead to defensive measures, potentially fracturing alliances built on mutual trust and shared interests. The tactic of using economic pressure to coerce a treaty ally into relinquishing territory is a departure from the "steadfast ally" role, signaling a shift towards a more opportunistic and potentially adversarial relationship.

"If he goes through with this, then it is existential for the alliance. If he does seek to use economic pressure to coerce Denmark into giving up Greenland, then I think it's going to sharpen a lot of minds in Europe."

This dynamic reveals how a leader's transactional approach, prioritizing tangible gains over relational capital, can undermine the very foundations of alliances. The "spirit of dialogue" at Davos, juxtaposed with these aggressive tactics, highlights the challenge of maintaining cooperation when one party operates on a fundamentally different, more unilateral principle. The conventional approach of appeasing or engaging in protracted negotiations, the "Ukraine playbook," may prove insufficient if the core objective is simply unilateral acquisition, irrespective of the systemic disruption it causes.

The Greenlanders' Perspective: Sovereignty Over Subsidies

Crucially, the narrative often centers on the geopolitical players, neglecting the perspective of the people who would be most directly affected: the Greenlanders themselves. Colchester's reporting from Nuuk reveals a population largely content with their current arrangement with Denmark, which provides a stable economic footing through subsidies and social services. While some may be curious about potential offers, the prevailing sentiment is one of wariness. The historical record of how other nations have dealt with indigenous populations, coupled with the potential influx of external economic interests, fosters a natural skepticism towards a US takeover.

"America has a bad record in dealing with indigenous people, and they know that. So I think the idea of letting in a load of mining prospects from America in return for cash is a model they've seen has not worked for others in the past. So I think they're wary."

This highlights a significant downstream consequence: the potential for internal resistance and the disruption of established social and political structures. The idea that Greenland is simply an unclaimed asset ripe for acquisition ignores the agency and established identity of its inhabitants. A strategy that bypasses or dismisses these considerations is inherently flawed, creating a long-term integration challenge that outweighs any immediate strategic or economic benefit. The "advantage" of acquiring Greenland, if it comes at the cost of alienating its population and destabilizing the region, proves to be a strategic liability. The immediate pain of addressing Greenland's economic realities and respecting its sovereignty would create a more durable, albeit less immediately gratifying, strategic position than a forced acquisition.

Actionable Takeaways for Navigating Complex Geopolitics

- Prioritize Long-Term Systems Thinking Over Immediate Transactions: Recognize that acquiring assets, especially territories, involves inheriting complex, ongoing costs and social structures. Understand the "money pit" reality before fixating on the "gold mine" potential. (Immediate Action)

- Map the Full Causal Chain of Coercive Tactics: When considering economic pressure, analyze not just the immediate desired outcome but also the predictable retaliatory responses and the long-term damage to alliances and international standing. (Immediate Action)

- Invest in Understanding Local Perspectives: Before making geopolitical plays, thoroughly research and engage with the existing populations and governance structures of the territory in question. Their buy-in, or lack thereof, is a critical factor in long-term success. (This pays off in 12-18 months as a foundation for future strategy)

- Acknowledge and Address Existing Subsidies and Economic Dependencies: If a territory relies on external financial support, factor the cost of maintaining or replacing that support into any acquisition plan. This is not a minor detail but a core component of the financial commitment. (Requires 3-6 months for detailed financial modeling)

- Distinguish Between "Solving a Problem" and "Creating a New One": A solution that addresses a perceived immediate need but creates significant downstream complexity, cost, or diplomatic fallout is not a true solution. (Ongoing Practice)

- Build Alliance Resilience Through Dialogue, Not Demands: Foster relationships based on mutual respect and shared interests. When disagreements arise, prioritize dialogue and de-escalation over threats of economic punishment, which erode trust. (This pays off in 1-3 years by strengthening partnerships)

- Develop Contingency Plans for Escalation: Recognize that aggressive actions can trigger unpredictable responses. Prepare for scenarios where initial demands are met with resistance, and have strategies for de-escalation that do not involve further coercion. (Immediate Investment)