Chinese Money Laundering Organizations Undercut Cartels Via Dual Markets

TL;DR

- Chinese money laundering organizations (CMLOs) undercut traditional money launderers by leveraging a dual revenue stream from both drug cartels and Chinese nationals seeking to move money abroad, charging significantly lower commissions.

- CMLOs exploit U.S. banking system weaknesses, such as slow suspicious activity report processing and a lack of real-time account closure, enabling them to deposit large sums with disregard for reporting limits.

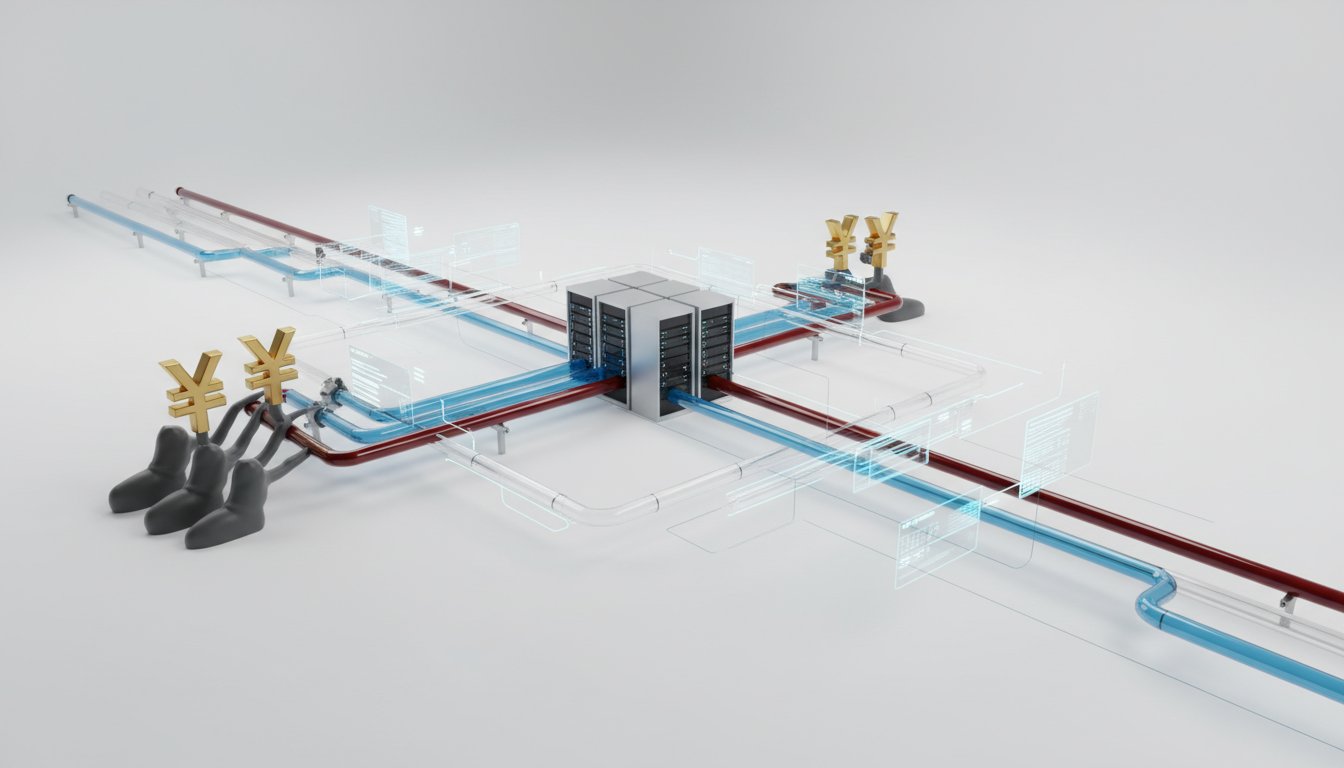

- The "two-sided market" model allows CMLOs to convert cartel drug proceeds into Chinese yuan, which are then used to purchase goods for sale in Mexico, effectively laundering money through trade.

- Encrypted messaging apps like WeChat, which do not cooperate with U.S. law enforcement, create significant investigative challenges for authorities, forcing reliance on labor-intensive surveillance methods.

- Law enforcement's ability to link money handlers to cartel members, as demonstrated by a grainy border crossing photograph, provides crucial evidence connecting illicit financial flows directly to drug trafficking operations.

- While successful operations like "Fortune Runner" disrupt specific networks, they represent only the "tip of the iceberg," indicating the vast scale and multiple laundering methods employed by cartels.

Deep Dive

Chinese money laundering organizations (CMLOs) are increasingly partnering with Mexican drug cartels, leveraging a two-sided market to move illicit funds at an unprecedented scale and efficiency. This sophisticated operation, characterized by aggressive bank deposits and the exploitation of China's capital controls, poses a significant challenge to traditional law enforcement methods, suggesting a need for systemic reform rather than isolated enforcement actions.

The rise of CMLOs is driven by China's strict 50,000 USD limit on outbound currency transfers, creating a strong demand among Chinese nationals in the U.S. for dollars. Simultaneously, these organizations serve Mexican drug cartels, who require efficient ways to launder vast sums of illicit cash. CMLOs bridge this gap by acting as money brokers, facilitating currency conversion for a commission. Because they have a revenue stream from Chinese nationals seeking to move money out of China, CMLOs can charge cartels significantly lower fees--often 1-2% compared to the traditional 5-10%--making them highly competitive and attractive to drug trafficking organizations. This price advantage allows CMLOs to capture substantial market share from established money launderers.

The operational model of CMLOs involves selling laundered drug money to Chinese nationals seeking U.S. dollars. The CMLOs are then left with Chinese yuan, which they use to purchase goods in China. These goods are then shipped to Mexico and sold for pesos, which are ultimately returned to the cartel. This trade-based money laundering system allows CMLOs to move both illicit funds and legitimate goods across borders, creating a complex web that is difficult for investigators to untangle. The sheer volume and efficiency of these operations are exemplified by figures like Sai Jiang, allegedly a key figure in "Operation Fortune Runner," who operated with apparent disregard for U.S. anti-money laundering regulations, making large, regular deposits that far exceeded the $10,000 reporting threshold.

Traditional law enforcement tactics are proving insufficient against these new methods. Wiretaps are ineffective due to CMLOs' reliance on encrypted messaging apps like WeChat, which are based in China and do not cooperate with U.S. authorities. This necessitates extensive physical surveillance, often involving long hours of observation to track couriers and their cash movements. Furthermore, banks' delayed reporting of suspicious activity, even when flagged multiple times, allows CMLOs to move millions through accounts before any meaningful investigation can occur. The case of Jia Yong Yu, who pleaded guilty to operating an unlicensed money remitting business after being caught with $100,000 in cash that a K9 unit alerted to narcotics, highlights the direct link between these laundering operations and drug trafficking, yet underscores the difficulty in dismantling the entire network.

The scale of these operations suggests that law enforcement's success in taking down individual groups, like the alleged network of Sai Jiang, represents only the tip of the iceberg. Cartels and CMLOs operate multiple laundering channels, ensuring that the disruption of one network does not cripple their overall financial operations. This reality points to a systemic challenge, indicating that while enforcement actions do create immediate impacts by forcing the development of new networks and requiring cartels to cover lost funds, they are not a panacea. The continued prevalence of CMLOs and their sophisticated methods signals a persistent and evolving threat that may necessitate a fundamental reevaluation of existing anti-money laundering frameworks.

Action Items

- Audit financial institutions: Identify 3-5 banks with high-volume cash deposits exceeding $10,000 to assess AML compliance (ref: Operation Fortune Runner).

- Track money laundering couriers: Monitor 5-10 individuals suspected of transporting illicit cash to identify patterns and connections to drug cartels.

- Analyze Chinese money laundering organizations (CMLOs): Map 3-5 CMLO operational models to understand their use of dual markets and undercut cartel competitors.

- Evaluate bank reporting procedures: Review the timeframes for filing suspicious activity reports (SARs) to identify bottlenecks in anti-money laundering defenses.

- Develop secure communication protocols: Investigate alternatives to encrypted messaging apps (e.g., WeChat) for law enforcement collaboration, given their non-cooperation with US authorities.

Key Quotes

"Federal officials say Chinese money launderers moved more than $300 billion in illicit transactions through U.S. banks and other financial institutions in recent years."

This quote from the episode description highlights the immense scale of illicit financial activity. Dylan Tokar, a reporter for WSJ, is exploring how these schemes operate and the federal investigation into them. This figure underscores the significant challenge law enforcement faces.

"Investigators allege that Yu is part of a new wave of sophisticated money launderers all with ties to China who are laundering money for powerful Mexican drug cartels and operating at such a scale and efficiency that it blows traditional money launderers out of the water."

Dylan Tokar explains that Jia Yong Yu is allegedly part of a sophisticated group with Chinese ties laundering money for Mexican drug cartels. This quote emphasizes the advanced nature and high efficiency of these new operations, distinguishing them from older methods.

"The money laundering side is a window into the larger organization you know if you want to pursue drug traffickers you could be on the street following people around watching them do deals watching them pass drugs to people and picking up money but it doesn't have any meaning until you actually start to see how the money that they are handling is getting to the people who actually own those drugs."

Julie Shemitz, a former federal prosecutor, articulates her guiding principle: "follow the money." She Schmitz explains that understanding money laundering provides crucial insight into the broader criminal enterprise, revealing how illicit funds connect back to the leaders of drug trafficking operations.

"There's a rule that limits how much money Chinese citizens can transfer out of the country. The cap is equivalent to about $50,000. The goal is to keep money in the Chinese financial system. The Chinese government really began to enforce this rule in 2016."

This quote, likely from Dylan Tokar, explains a key factor driving the rise of Chinese money laundering organizations. The Chinese government's strict enforcement of currency export limits since 2016 creates a demand for alternative methods to move money out of China.

"When a Chinese national in the United States gets money from a money broker from China, they pay a commission on it and they pay a hefty commission on it and this enables the Chinese underground banking organizations to charge less to the narcotics trafficking organizations for whom they are laundering those funds."

Dylan Tokar details how Chinese money laundering groups gain a competitive advantage. By leveraging commissions from Chinese nationals needing to convert currency, these organizations can offer lower rates to drug cartels, undercutting traditional money launderers.

"The way they're approaching the banks is they don't care whether the banks are going to flag the amount of money they don't care they're regularly depositing much more than $10,000 and basically they know that the bank is flagging this and they know that the bank could at some point shut down the account but in their experience the bank doesn't do that very fast."

Dylan Tokar describes the reckless approach of these sophisticated money launderers. He explains that they intentionally exceed bank reporting limits, understanding that while banks flag these transactions, the process to shut down accounts is slow, allowing them to operate with relative impunity.

"Wechat is based in China and they do not cooperate with U.S. law enforcement so unlike some other platforms there is no way to get information about subscribers or traffic on Wechat or certainly the content of any Wechat messages."

Julie Shemitz highlights a significant investigative challenge. She Schmitz explains that the encrypted nature and lack of cooperation from platforms like WeChat, which are based in China, prevent U.S. law enforcement from accessing crucial communication data, hindering investigations.

"I think it's the tip of the iceberg. I think there's a ton more going on. This is the challenge I think of being someone who in law enforcement who who is up against the the cartels. I mean they're operating at such a huge scale."

Julie Shemitz expresses her perspective on the scope of the problem. She Schmitz believes that the operation taken down is only a small part of a much larger network, emphasizing the immense scale at which cartels operate and the ongoing challenge for law enforcement.

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "The Wire" - Mentioned as a television series that is difficult to watch due to its realism concerning money laundering.

Articles & Papers

- WSJ’s Dylan Tokar explores the rise of these highly lucrative schemes (The Journal) - Mentioned as context for the episode's reporting on Chinese money launderers.

- A Wall Street Journal analysis last year estimated that more than 250 billion had left China in a 12 month period (The Journal) - Referenced to illustrate the scale of money leaving China.

People

- Dylan Tokar - WSJ reporter whose work is featured in the episode.

- Julie Shemitz - Former federal prosecutor with expertise in money laundering.

- Ryan Knutson - Host of The Journal podcast.

- Jia Yong Yu - Individual arrested in connection with money laundering operations.

- Sai Jiang - Alleged ringleader of a Chinese money laundering network.

Organizations & Institutions

- Mexican drug cartels - Mentioned as clients of Chinese money laundering organizations.

- U.S. banks - Discussed as institutions through which illicit transactions are moved.

- Department of Justice (DOJ) - Mentioned as the agency where Julie Shemitz previously worked.

- Sinaloa Cartel - Identified as one of the most powerful drug cartels.

- JP Morgan Chase - Bank whose anti-money laundering program was mentioned in relation to a specific case.

- Homeland Security - Agency involved in border alerts for targets.

- New York authorities - Mentioned for arresting a lieutenant of Sai Jiang.

- Southgate Police Department - Law enforcement agency involved in the detainment of Jia Yong Yu.

Websites & Online Resources

- wsj.com - Mentioned as the source for a newsletter.

- megaphone.fm/adchoices - URL provided for managing ad choices.

- usbank.com - Website for U.S. Bank.

- servicenow.com - Implied website for ServiceNow.

- applecard.com - Website for Apple Card.

- firstnet.com/publicsafetyfirst - Website for FirstNet.

Other Resources

- Operation Fortune Runner - A year-long investigation into a Chinese money laundering ring.

- Chinese Money Laundering Organizations (CMLOs) - Acronym used by authorities to refer to Chinese money laundering groups.

- WeChat - Encrypted messaging app used by Chinese money launderers, noted for not cooperating with U.S. law enforcement.

- Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) - Reports banks are required to file, discussed in the context of their effectiveness in combating money laundering.

- Miranda rights - Legal rights read to an arrested individual.

- Operation Fortune Runner investigation - Mentioned as the basis for the episode's account of Sai Jiang's alleged scheme.

- Chinese underground banking organizations - Entities that facilitate currency conversion and charge commissions.

- Two-sided market - Concept describing the exchange between Chinese money launderers and drug cartels.