Shifting From Equality to Structure for Dynamic Instructional Balance

TL;DR

- True balance in teaching involves strategically varying the emphasis on different instructional components, rather than striving for strict equality, to meet evolving student needs.

- Prioritizing number sense development or targeted practice based on immediate student struggles creates a more effective, albeit unequal, instructional structure than uniform distribution.

- Applying the "rock structure" analogy, effective math coaching requires balancing diverse support methods like modeling, observation, and co-planning, not just equal time allocation.

- Over-allocating time to one aspect of instruction, like number sense, can be a deliberate foundation-laying strategy, not necessarily an imbalance, for future learning.

- Shifting from an "equality" mindset to a "structure" mindset in lesson planning allows for dynamic adjustment of component sizes to achieve genuine pedagogical balance.

Deep Dive

True balance in teaching, particularly in mathematics, is not about striving for exact equality between different instructional activities. Instead, it requires creating a dynamic, well-structured approach where the emphasis on various components adjusts based on current student needs, much like a carefully constructed rock sculpture. This nuanced understanding prevents the exhaustion that arises from pursuing an unattainable ideal of perfect equality and instead fosters a more effective and responsive learning environment.

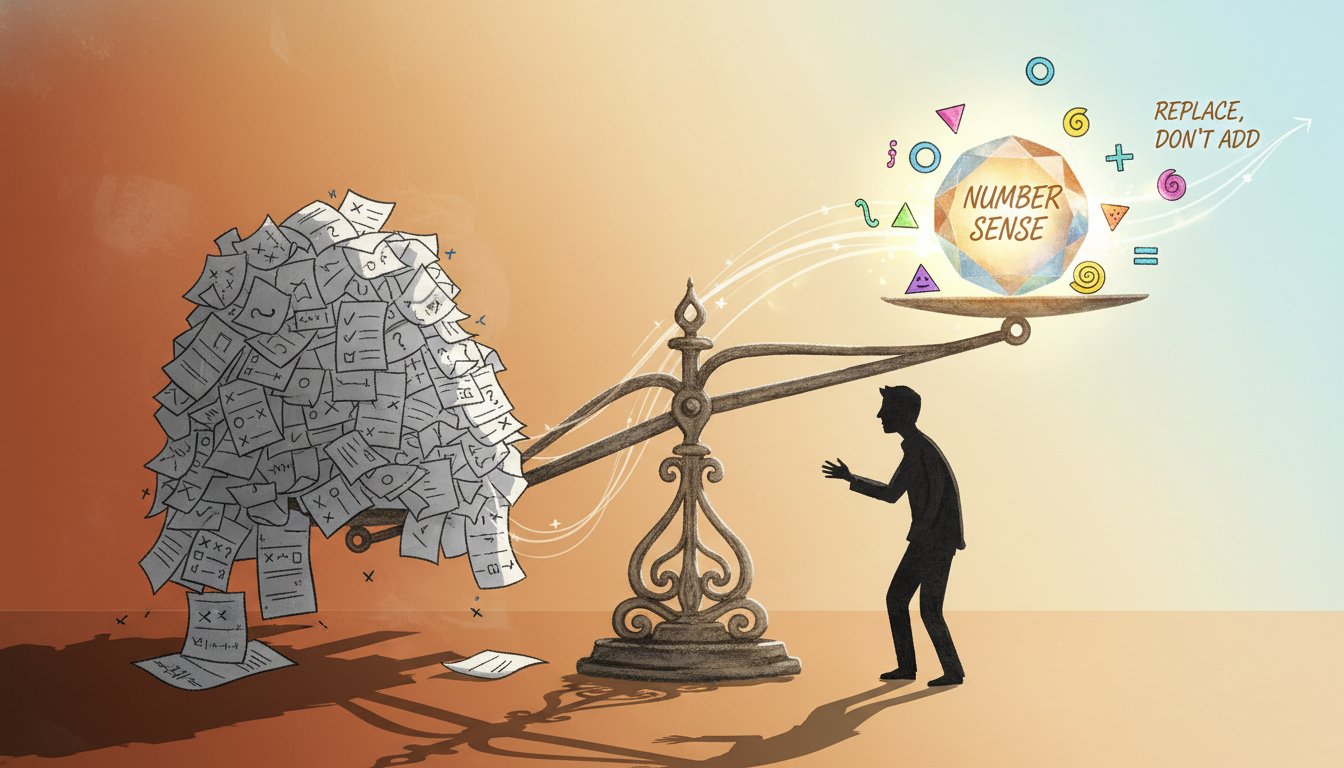

The common perception of balance as a measurement scale, where every activity must be matched by an equal counterpart, leads to an unsustainable and ineffective teaching practice. For instance, equating time spent on number sense with time spent on fact drills, or model lessons with teacher observations, creates a false equivalence. This approach, while seemingly fair, fails to account for the varying developmental stages and immediate needs of students. The consequence of this "equality" mindset is a pedagogical exhaustion that does not translate into improved student outcomes. The core implication is that pursuing strict equality in instructional time and focus can inadvertently lead to a deficit in either conceptual understanding or procedural fluency, as neither area receives the appropriate emphasis when needed.

In contrast, genuine balance is analogous to a rock sculpture, where different-sized rocks are artfully arranged to create stability and aesthetic appeal. Some rocks are large and foundational, representing significant instructional focus, while others are smaller, interspersed to provide variety and support. This means that if students are struggling with multiplication facts, a larger emphasis might be placed on number sense activities that build conceptual understanding of multiplication relationships. This larger "rock" of number sense development is then complemented by smaller "rocks" of interspersed practice, rather than an equal block of drill and practice. Similarly, math coaches should balance modeling lessons with observations and co-planning, adjusting the size of each activity based on the teacher's current needs. This principle extends to personal lives, where different areas naturally require more attention at various times. The second-order implication is that a flexible, needs-based approach to instructional design allows for more targeted interventions and a deeper, more robust understanding for students, preventing the pitfalls of over-emphasis on one skill set at the expense of another.

Ultimately, the critical takeaway is that effective teaching and coaching demand a shift from an equality-driven model to a balance-driven one. By recognizing that different mathematical experiences are needed in varying amounts at different times, educators can create a powerful, beautiful, and truly balanced structure that meets students where they are. This approach not only prevents pedagogical burnout but also ensures that students develop both the conceptual understanding and the efficiency required to build strong math minds.

Action Items

- Design math instruction: Adjust emphasis on number sense, efficiency, and application based on student needs, not equal time allocation.

- Audit coaching practices: Evaluate balance between modeling, observation, and co-planning to meet teacher needs, not just equal distribution.

- Create lesson plans: Intersperse practice rocks within number sense or application activities, rather than dedicating equal blocks of time.

- Assess personal workload: Identify which life "rocks" require larger emphasis temporarily to build a balanced personal structure.

Key Quotes

"When I say the word balance, what comes to mind? For most of us, we picture that measurement scale, right? Like, if I do this to this side, I have to do this to the other side to make it balance out, so it's not one side higher than the other. So, it's all about balancing those two sides."

Christina Tondevold explains that the common understanding of balance, like a measurement scale, implies an equal distribution of effort or focus between two sides. This perspective suggests that any emphasis on one area necessitates an equivalent emphasis on another to achieve equilibrium.

"In my life, if I spend too much time working, I feel like I need to balance it out with family time to make it even out, right? When you're teaching, if you do too much number sense work, you feel like you need to have that same amount in practice and drill. If I spend this much time on problem solving, then I better spend equal time on fact fluency."

Christina Tondevold illustrates the pervasive nature of this "equality" mindset by showing how it applies to personal life and teaching practices. She notes that this approach leads to a feeling of obligation to match time spent on one activity with an equal amount of time on another, such as balancing number sense with drill and practice.

"But that's not actually balance. That's equality. And they're not the same thing."

Christina Tondevold directly challenges the conventional interpretation of balance, asserting that the pursuit of equal distribution is, in fact, equality, not true balance. She emphasizes that these two concepts are distinct and that mistaking one for the other leads to an incorrect approach.

"Real balance, I feel like, looks like this. And if you're just listening, here's what I'm showing. Have you ever seen those beautiful rock structures where the rocks are balanced on top of each other? Some rocks are bigger, some are wider, some are different colors, they're made of different material, different rocks. They're not all the same. They're not equal. But it's balanced."

Christina Tondevold introduces an alternative metaphor for balance, using the image of a rock structure. She describes how these structures are stable and aesthetically pleasing despite the varied sizes, shapes, and materials of the individual rocks, highlighting that balance does not require uniformity.

"The balance comes from knowing what your students need right now and adjusting accordingly. And when you really look at what your students are needing, you will find that sometimes you need bigger and smaller amounts of things to create that perfect balanced rock structure."

Christina Tondevold argues that true balance in teaching is dynamic and responsive, stemming from an accurate assessment of student needs. She explains that this understanding allows educators to adjust the emphasis on different instructional components, using varying amounts to create a stable and effective learning environment.

"Balance isn't about equality. It's about meeting your students or the teachers you're coaching where they are and giving them what they need when they need it."

Christina Tondevold reiterates her core argument, stating that balance is fundamentally about responsiveness and targeted support rather than strict adherence to equal measures. She concludes that effective balance involves providing specific resources and attention based on the current requirements of students or coachees.

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "The Balanced Rock Structure" - Mentioned as an analogy for real balance in teaching.

Articles & Papers

- "Why Balance in Teaching Isn't What You Think" (The Build Math Minds Podcast) - Discussed as the central theme of the episode, contrasting equality with true balance in instruction.

People

- Christina Tondevold - Host of The Build Math Minds podcast and founder of buildmathminds.com.

Organizations & Institutions

- Build Math Minds - Podcast and website focused on changing elementary math instruction.

Websites & Online Resources

- BuildMathMinds.com/215 - Provided as the URL to access resources mentioned in the episode.

Other Resources

- Balance vs. Equality in Teaching - Central concept discussed, differentiating the two ideas in educational contexts.

- Rock Structure Analogy - Used to illustrate the concept of real balance in teaching, where elements are varied in size and emphasis.