Leicester Longwool Sheep: Protected Technology, Political Protest, and Preservation

The humble Leicester Longwool sheep, a seemingly simple farm animal, carries a profound historical narrative that reveals the intricate interplay of innovation, protectionism, and the enduring pursuit of economic and political independence. This conversation unveils how a breed once guarded as a national treasure, smuggled across oceans, and ultimately declared extinct, found its way back to American soil, not merely as a historical curiosity, but as a testament to the long-term value of preserving genetic heritage and the surprising ways national identity can be woven into the fabric of livestock. Anyone invested in understanding the roots of American self-sufficiency, the economics of protected industries, and the resilience of endangered heritage will find strategic advantage in grasping these layered consequences, which extend far beyond the charming spectacle of lambing season.

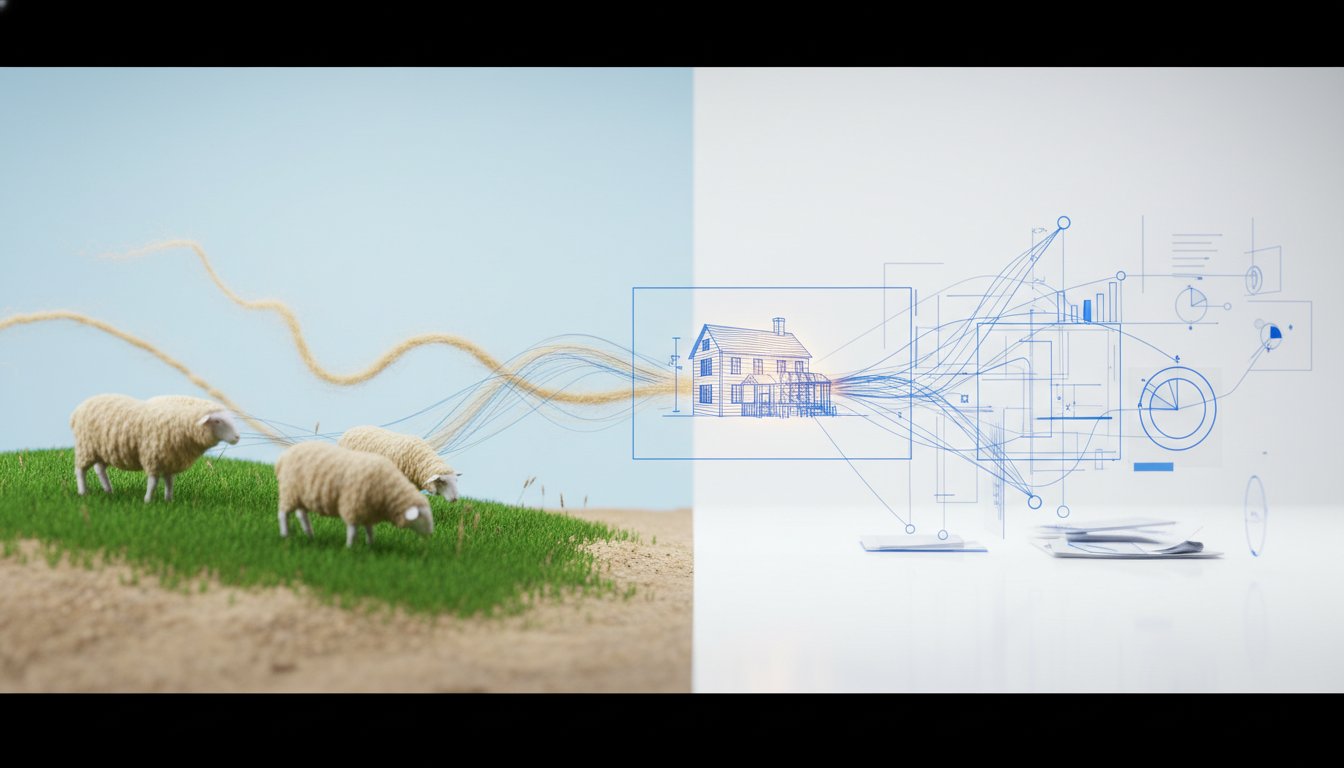

The story of the Leicester Longwool sheep at Colonial Williamsburg is a masterclass in consequence mapping, demonstrating how a single breed's journey mirrors broader historical and economic forces. It’s a narrative that begins not with a desire for cute lambs, but with a calculated effort to control a vital industry. Robert Bakewell, in 18th-century England, didn't just breed sheep; he engineered a "designer breed," the Leicester Longwool, specifically for meat and superior wool. This wasn't just about animal husbandry; it was about creating a valuable commodity.

The British, acutely aware of the economic power of their textile industry, treated breeds like the Leicester Longwool as protected technology. Laws were enacted to prevent the colonies from developing their own wool production and, crucially, to stop these prized sheep from leaving Britain. This protectionist stance, while intended to bolster the British economy, inadvertently sowed the seeds of discontent and a desire for self-sufficiency in the American colonies.

"The British were very protective of their textiles. They passed all sorts of laws banning the colonies from producing their own wool and exporting it. Believe it or not, they also banned sheep like the longwools from being sent out of Britain. These sheep were essentially a protected technology."

This prohibition, however, created a black market. Wealthy planters, including none other than George Washington, engaged in "illicit under the table sheep trading." Washington’s correspondence reveals his awareness of these British statutes and his subtle acknowledgment of "less scrupulous people" who circumvented them. This wasn't just about acquiring better wool; it was a political act. The desire for Leicester Longwools became intertwined with the burgeoning movement for economic independence, a tangible way for farmers to protest British control and build their own capacity. The immediate benefit of acquiring these sheep was the promise of better wool, but the downstream consequence was a subtle, yet significant, act of defiance that contributed to the political climate leading to the American Revolution.

The narrative then shifts, illustrating how technological advancement can disrupt established advantages. The arrival of the Merino sheep from Spain, with their softer, finer wool, rendered the Leicester Longwool, once the "gold standard," obsolete in the American market by the 1940s. This led to the breed's extinction in the United States. This extinction highlights a critical lesson: what is valuable today can be superseded tomorrow. The Merino's success wasn't just about a better product; it was about a new standard that fundamentally altered market demand, leaving the once-prized Leicester behind. The loss of genetic material, once gone, is permanent, a stark reminder of the fragility of heritage breeds when faced with disruptive innovation.

"By the 1940s, the Leicester Longwool was completely extinct in the United States. And you know that's kind of a problem because once you lose some of this genetic material, it's gone forever."

The story finds its resolution, and a profound second-order positive consequence, with the establishment of Colonial Williamsburg's Rare Breeds Program in the mid-1980s. The goal was to reintroduce animals vital to 18th-century American life. The effort to bring back the Leicester Longwool required tracking down a flock in Australia and re-establishing it in the United States. This wasn't a quick fix; it was a long-term investment in historical preservation and genetic restoration.

The immediate discomfort of shearing sheep with antiquated shears, a deliberate choice to maintain historical authenticity, underscores a key principle: embracing difficulty for lasting advantage. While electric clippers would be faster, they would undermine the immersive 18th-century experience Colonial Williamsburg aims to provide. This commitment to historical accuracy, even when it involves more labor, creates a unique value proposition. The Leicester Longwools, once extinct, are now listed as "threatened" in North America, a significant success for the rare breeds program. This revival demonstrates how a conscious effort to reverse a loss can create a durable, unique asset. The wool from these sheep, now used for rugs, blankets, and even yarn sold in gift shops, offers a tangible connection to the past--a "farm to table, but for cloth" experience that provides a competitive advantage through authenticity. The presence of these sheep, and the sounds they make, contribute to the immersive atmosphere, a subtle but powerful element that differentiates the experience from a mere historical display.

- Immediate Action: Engage with historical narratives that connect seemingly simple elements (like sheep) to complex historical forces (like economic independence and technological disruption).

- Immediate Action: Recognize that "obvious" solutions or technologies can have unforeseen negative downstream consequences, particularly in complex systems.

- Immediate Action: Observe how protectionist policies, while intended to safeguard an industry, can foster illicit markets and contribute to political dissent.

- Longer-Term Investment: Support initiatives focused on preserving genetic diversity and heritage breeds, understanding that this is a form of cultural and historical insurance.

- Longer-Term Investment: Embrace practices that require more effort in the present (e.g., historical shearing methods) if they create a unique, durable advantage and authenticity in the long run. This pays off in 12-18 months through enhanced visitor experience and brand differentiation.

- Discomfort for Advantage: Actively seek out and implement strategies that involve immediate discomfort or extra effort, as these are often the very factors that deter competitors and create lasting moats. This requires patience and a focus on long-term value over short-term efficiency.

- Systemic Thinking: Analyze how seemingly isolated elements (a sheep breed) are interconnected with broader economic, political, and technological systems, and how changes in one area can cascade through others.