Home Hardening Empowers Residents Against Wildfire Ember Ignitions

This conversation delves into the critical, often overlooked, systemic challenges of wildfire response, highlighting how traditional top-down approaches are failing in the face of escalating threats. It reveals the hidden consequence that relying solely on external emergency services creates a dangerous dependency, leaving communities vulnerable when those services are overstretched. The core thesis is that true resilience emerges not from waiting for rescue, but from proactive, community-driven "home hardening" and mutual aid, a paradigm shift that requires individuals to embrace immediate discomfort for long-term safety. Anyone living in or near fire-prone areas, and policymakers grappling with disaster preparedness, will gain a crucial advantage by understanding this layered approach to risk mitigation.

The Illusion of Rescue: Why "We'll Protect You" is No Longer Enough

The prevailing narrative around wildfire response, and indeed many large-scale emergencies, is one of a heroic, well-equipped external force arriving to save the day. This "hero saving victim paradigm," as described by Adriana Cargill, has fostered a dangerous passivity in communities. While it offers a comforting illusion of safety, it’s a system fundamentally incapable of scaling to meet the growing intensity and frequency of modern wildfires. Dr. Jack Cohen's decades of research reveal a stark reality: homes are igniting not from the direct inferno of the wildfire, but from burning embers carried miles ahead, often without the fire even reaching the community. This insight fundamentally reframes the problem. It’s not about stopping an unstoppable force at the perimeter; it’s about making individual homes less susceptible to ignition in the first place.

The consequence of this passive reliance is clear: when multiple catastrophic fires erupt simultaneously, as seen in California, emergency responders are stretched impossibly thin. The former chief of LA County Fire’s stark admission of having "700 engines to protect 50,000 houses" underscores the mathematical impossibility of traditional response models. This isn't a failure of resources; it's a fundamental mismatch between the scale of the threat and the proposed solution. The immediate benefit of waiting for help is psychological comfort, but the downstream effect is a community left defenseless when that help cannot materialize.

"We only had 700 engines to protect 50,000 houses. So that's the exposure 50,000 houses exposed across a wide area there. It's an absolute impossibility."

-- Former Chief of LA County Fire (as recounted by Adriana Cargill)

This realization forces a critical re-evaluation of responsibility. The conventional wisdom, deeply ingrained in a culture of "fire protection taking responsibility for protecting us," is failing. The community brigade’s approach, therefore, represents a necessary evolution, shifting focus from reactive rescue to proactive preparedness. This bottom-up, community-level change isn't just a supplementary strategy; it's becoming the primary mechanism for resilience in the face of an accelerating crisis.

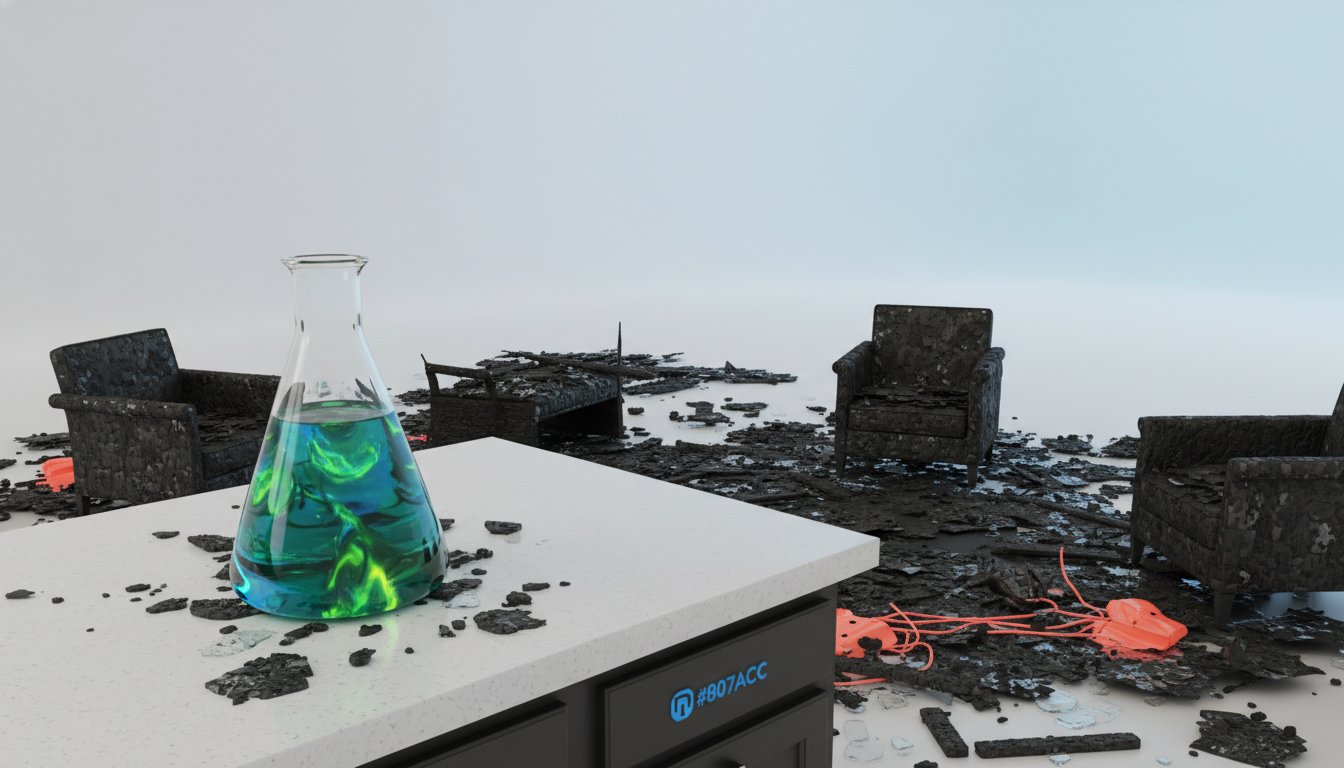

Home Hardening: The Unseen Battle Against Embers

Dr. Jack Cohen’s pioneering work on home hardening directly challenges the notion that wildfire destruction is an all-or-nothing event dictated by the uncontrollable inferno. His research reveals that the vast majority of home ignitions are caused by burning embers, a phenomenon that offers a crucial lever for intervention. This insight is powerful because it shifts the locus of control from the uncontrollable external wildfire to the controllable immediate environment of the home. The implication is that by addressing small, seemingly insignificant details, communities can dramatically reduce their vulnerability.

The science is clear: "embers' ability to penetrate into the flammable interiors of the house" is the primary ignition pathway. This means that simple, actionable steps like clearing "rain gutters full of leaf debris and dead material," removing "firewood," "debris in our gutters," or "debris in the carport," and ensuring "charcoal briquettes and lighter fluid" are stored safely away from barbecues, are not mere suggestions but critical preventative measures. These actions directly reduce the fuel load that embers can ignite. The consequence of neglecting these details is that a home, even surrounded by "unconsumed tree canopies," can still be lost.

"The embers' ability to penetrate into the flammable interiors of the house -- so those kind of preparatory little things can make all the difference where the wildfire isn't actually making contact with the structure."

-- Dr. Jack Cohen

This is where the concept of "delayed payoff" becomes critical. Implementing home hardening measures requires immediate effort and, frankly, can feel like busywork. It doesn't offer the immediate gratification of seeing a fire put out or the dramatic visual of a building being saved. Instead, its benefits are realized in the absence of destruction -- a quiet victory that is easily overlooked. Conventional wisdom often favors quick fixes or visible actions. Home hardening, however, demands patience and a long-term perspective. It’s an investment that pays off not in immediate relief, but in the durable advantage of a home that simply doesn't ignite when the embers fly. This is precisely why it creates a competitive advantage: it’s difficult, requires sustained effort, and lacks the immediate emotional reward that drives many behavioral changes.

The Zone Zero Gap: Regulation vs. Implementation

While the science of home hardening is robust, its widespread adoption faces significant systemic hurdles, particularly concerning regulation and implementation. Adriana Cargill highlights the "Zone Zero law" in California, a statewide bill aimed at addressing home ignition zones. However, its lack of effective implementation, even years after its passage, reveals a critical gap between policy intent and on-the-ground reality. This illustrates a common pattern: well-intentioned legislation often struggles to keep pace with the accelerating reality of climate-driven disasters.

The current fire codes, as Cargill notes, primarily focus on "building materials" -- ensuring houses use fire-resistant materials. While important, this addresses only one facet of the ignition problem. The crucial element of the "home ignition zone," encompassing landscaping and immediate surroundings, remains a murkier area with less stringent enforcement. This creates a situation where, even if a home is built with fire-resistant materials, its vulnerability can be significantly increased by unaddressed external fuel sources. The immediate consequence of this regulatory gap is that homeowners who rely solely on building codes may still be at high risk.

"As far as landscaping and the home ignition zone, which is a lot of what Jack Dr. Cohen's work focuses on, it gets a little bit murkier."

-- Adriana Cargill

The implication here is that relying on government mandates alone is insufficient. The "hero saving victim paradigm" extends to regulatory frameworks, where the expectation is that codes will protect us. However, as the community brigade demonstrates, effective fire protection requires a "yes and" approach, integrating institutional change with grassroots action. The slow pace of institutional change, exemplified by the delayed implementation of Zone Zero, necessitates a bottom-up movement. This is where the community brigade’s focus on education and mutual aid becomes paramount, empowering residents to take direct action in areas where formal systems are lagging. The advantage lies with those who understand this dynamic and proactively bridge the gap between policy and practice, recognizing that true safety requires individual agency alongside systemic support.

Key Action Items

-

Immediate Action (Next 1-3 Months):

- Conduct a Home Ignition Zone Assessment: Walk around your property and identify all sources of flammable material within 30 feet of your home (e.g., dead leaves in gutters, firewood piles, dry vegetation near the foundation, flammable items on decks).

- Clear Gutters and Roofs: Remove all accumulated debris from rain gutters and the roof. This is a critical, low-effort, high-impact action.

- Remove Flammable Materials from Immediate Vicinity: Relocate firewood piles, propane tanks, and other combustible materials away from the house. Store charcoal briquettes and lighter fluid in a safe, enclosed location away from ignition sources.

- Begin Landscaping for Fire Resistance: Start replacing highly flammable plants with more fire-resistant species. Create defensible space by reducing continuous vegetation.

-

Short-Term Investment (Next 3-6 Months):

- Upgrade Vents and Openings: Install ember-resistant vents on attics, crawl spaces, and under decks to prevent ember intrusion. Seal gaps and cracks in the home's exterior.

- Consider Ember-Resistant Window Treatments: If budget allows, explore upgrading windows to dual-paned, tempered glass, which are more resistant to heat and breakage from embers.

-

Long-Term Investment (6-18 Months and Beyond):

- Retrofit or Rebuild with Fire-Resistant Materials: For older homes, plan for retrofits that incorporate fire-resistant siding, roofing, and decking. For rebuilds, ensure compliance with the latest fire-resistant building codes and beyond.

- Establish Community Mutual Aid Networks: Connect with neighbors to form local brigades or support networks for coordinated preparedness, evacuation assistance, and post-fire recovery efforts. This builds a resilient community infrastructure that supplements official response.

- Advocate for Policy Implementation: Engage with local and state representatives to push for the effective implementation and enforcement of fire-safe landscaping regulations and building codes, like the Zone Zero law.