Pollock Painting Theft: Decades of Legal, Financial, and Emotional Turmoil

This podcast episode, "The hunt for a stolen Jackson Pollock painting," offers a profound exploration of how a single act of theft can unravel decades of emotional and financial stability, revealing hidden consequences far beyond the immediate loss of property. It delves into the complex interplay between art, friendship, fame, and trauma, demonstrating how the pursuit of a missing masterpiece becomes a journey through personal history and the enduring impact of unresolved loss. Anyone invested in understanding the deep, often invisible currents that shape our lives--from the value we place on material possessions to the psychological weight of past events--will find compelling insights here. The advantage this analysis provides is a framework for recognizing how seemingly isolated incidents can create cascading effects across personal, familial, and even legal systems, offering a lens through which to view their own experiences of loss and recovery.

The Lingering Shadow of a Stolen Masterpiece

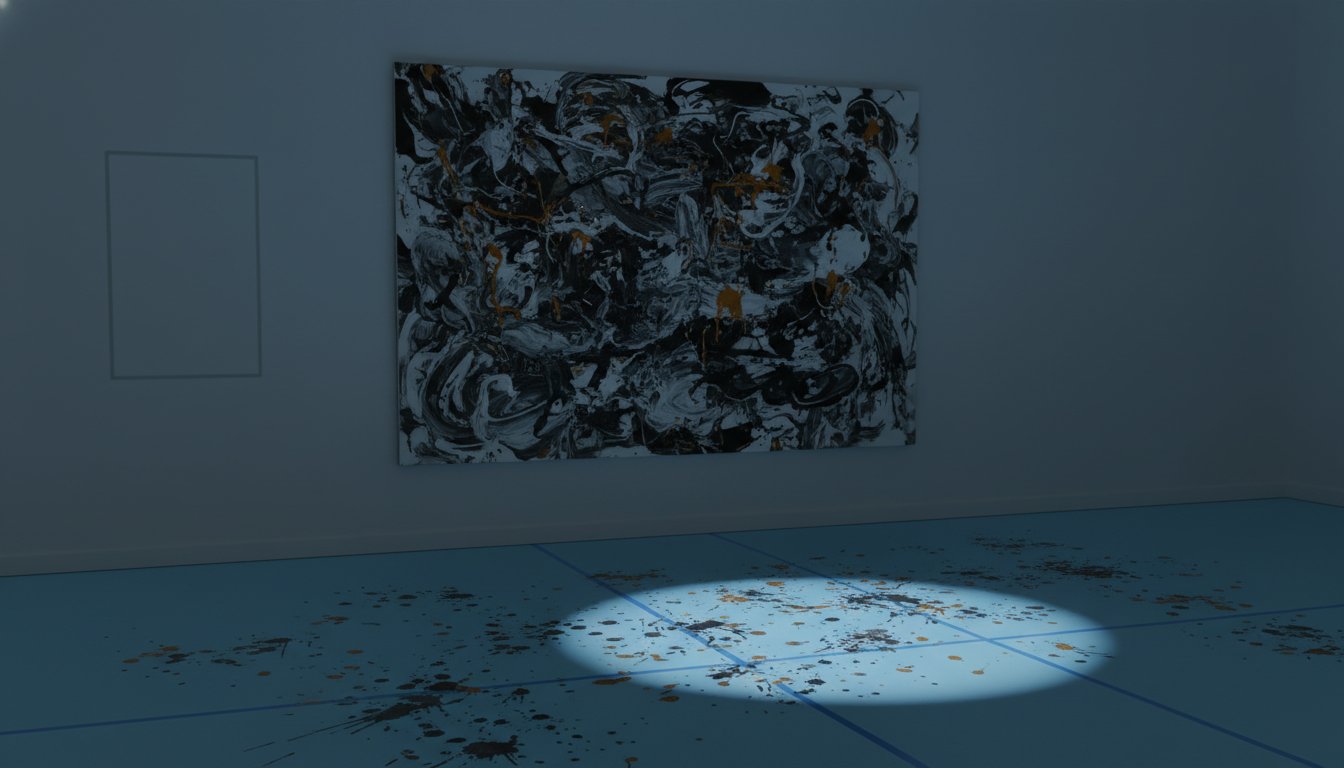

The narrative of the stolen Jackson Pollock paintings from the Isaacs family home in 1973 is not merely an account of a high-profile art heist; it is a masterclass in consequence mapping. Sebastian Smee meticulously reconstructs how the theft of three of Pollock's works--specifically "Number 7, 1951," "Number 21, Untitled with Poles, 1949," and "Painting 10/28, 1948"--unleashed a decade of turmoil, anxiety, and financial distress for Reginald Isaacs, a Harvard professor and close friend of the artist. The immediate impact was devastating: Isaacs's "peace of mind, fragile at the best of times, was destroyed." This wasn't just about losing valuable assets; it was about the erosion of his sense of security and his ability to function. The transcript highlights how his notes from this period devolved into "scattered with sequences of numbers and crossed out lists and half formed semi legible sentences that peter out into nothing," illustrating the profound psychological toll. This descent into disarray underscores a critical system dynamic: the failure to adequately secure valuable assets, especially those imbued with significant personal and financial meaning, creates a vulnerability that can be exploited, leading to a cascade of negative outcomes.

The story powerfully illustrates how conventional wisdom--that insurance adequately covers such losses--fails when confronted with the messy reality of legal battles and complex valuations. Isaacs, an academic rather than a businessman, lacked an "elaborate insurance policy." The subsequent legal wrangling over negligence and liability transformed his life into a "snake pit." This delayed payoff, a decade of legal and financial entanglement, created a competitive disadvantage for Isaacs, draining his resources and mental energy. The immediate action of theft led to a protracted, agonizing process of attempting to reclaim what was lost, a process that ultimately outlived him.

"The feeling white had that day in the national gallery was overwhelming... after she stood up and showed him the label which had her father's name on it reginald isaacs."

-- Sebastian Smee

This quote, describing Mary White's visceral reaction to seeing "Number 7, 1951" in a gallery years after its theft, encapsulates the enduring emotional residue of the event. It wasn't just a painting; it was a tangible link to her father's distress and a symbol of a profound violation. The narrative reveals that the consequences of the theft extended beyond Reginald Isaacs, deeply affecting his daughter Mary White, who harbored complex feelings towards Pollock due to his volatile nature and the uncomfortable visits to his home. The stolen painting above her childhood bed became a constant, painful reminder. This highlights a second-order consequence: the intergenerational emotional inheritance of trauma stemming from a singular event. The theft didn't just impact Reginald; it imprinted itself on Mary's memory and emotional landscape.

The Unforeseen Value of Delayed Resolution

The recovery of the paintings, particularly "Number 7, 1951," demonstrates a fascinating dynamic of delayed payoff and the competitive advantage it can create, albeit unintentionally. The investigation into the theft of other art from a fellow Harvard professor, Stuart Cary Welch, led to the arrest of Daniel E. Levens and Patrick L. Dunn. Crucially, Isaacs's attorney, George Abrams, leveraged the potential for leniency for the defendants by suggesting they provide information leading to the return of the Isaacs's Pollooks. This strategic move, born out of the interconnectedness of art crimes in the region, eventually led to the recovery of "Number 7, 1951."

This process took years, involving a sting operation, court trials, and further investigation. The immediate discomfort for Isaacs--reluctantly participating in legal proceedings, facing potential publicity, and enduring ongoing stress--was immense. However, this prolonged struggle eventually yielded a significant financial settlement and the recovery of one of the stolen works. The narrative implies that had the theft been resolved quickly, or had Isaacs given up, this specific avenue of recovery might have closed. The system, in this case, responded to persistent legal pressure and the interconnectedness of criminal activity, creating a delayed but substantial payoff.

"What keeps me going at all george is my responsibility to my wife children and grandchildren"

-- Reginald Isaacs

This poignant quote from a letter by Reginald Isaacs to his lawyer, George Abrams, reveals the immense personal burden he carried throughout the decade-long ordeal. It underscores the profound emotional and psychological cost of the unresolved theft, demonstrating that the consequences extended far beyond financial loss. His motivation to persevere was rooted in his familial obligations, highlighting how personal values can drive individuals through protracted and draining challenges. This also points to a systemic failure in security that, while not immediately apparent, created an environment where such prolonged suffering was possible.

The story also touches upon the eventual recovery of "Number 21, Untitled with Poles, 1949." Its reappearance at a gallery, initially misidentified and then correctly authenticated through painstaking detective work and an old photograph, illustrates how even seemingly lost elements can resurface. The delay in its identification and recovery--years after the initial theft and even after the first painting was returned--meant that Reginald Isaacs did not live to see its full resolution. This underscores the tragic reality that some consequences manifest over timescales that exceed an individual's lifetime, leaving a legacy of unfinished business for heirs. The eventual sale of this second painting for $500,000, with a significant portion going towards Isaacs's widow's care, shows a long-term, albeit posthumous, financial benefit derived from the initial loss. This highlights how delayed resolution, while painful, can sometimes lead to a more favorable outcome than immediate capitulation.

The Unseen Value of Patience and Persistence

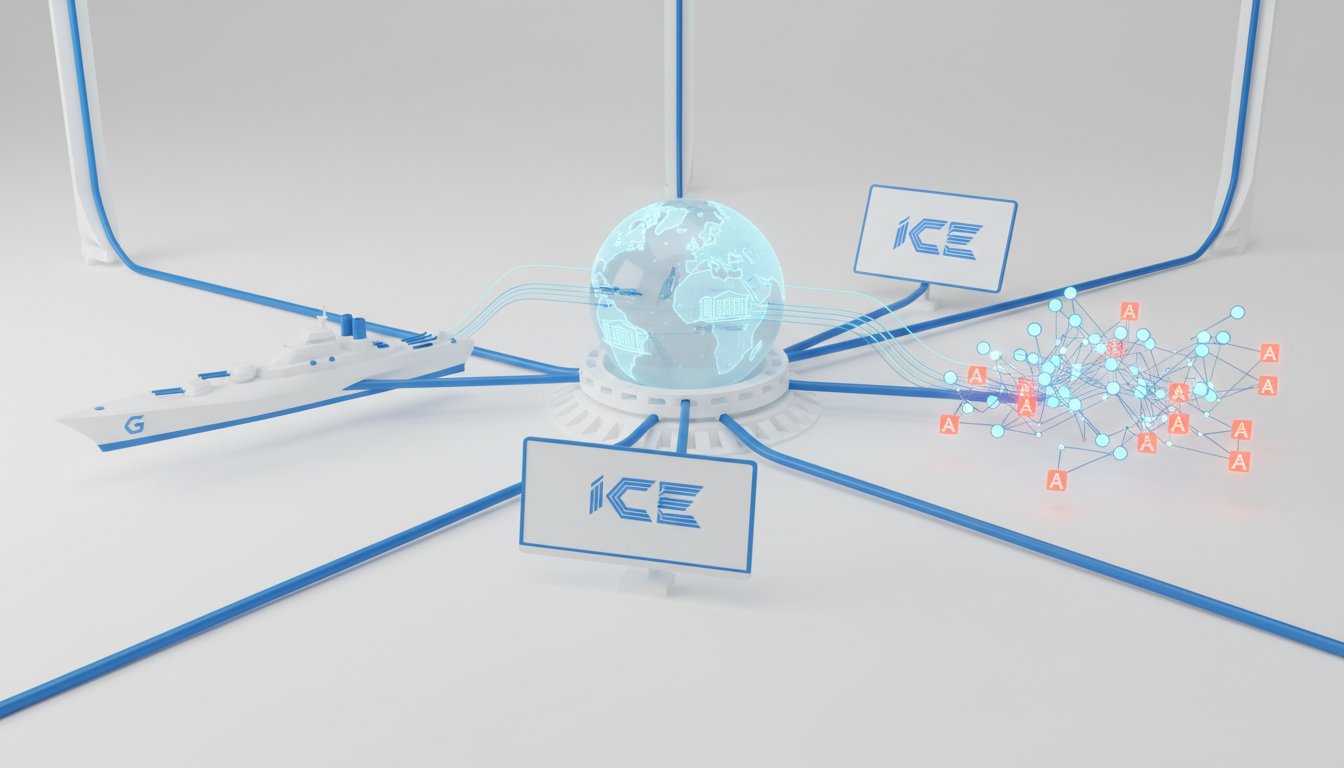

The third painting, "Painting 10/28, 1948," remains missing, representing the ultimate unresolved consequence. The narrative hints at a potential recovery through a Homeland Security investigation in Paris involving a Picasso theft, suggesting a broader network of art recovery and negotiation. However, the source went silent, leaving this final piece of the puzzle elusive. This ongoing absence serves as a stark reminder of the inherent uncertainties in recovering stolen cultural heritage and the limits of even sophisticated investigative efforts.

The story implicitly criticizes approaches that prioritize immediate solutions or quick fixes. The theft itself was a swift act, but the ramifications were enduring. The subsequent investigations and legal battles were protracted, demanding immense patience and persistence from those involved, particularly from George Abrams and, to a lesser extent, Mary White. The conventional wisdom might suggest moving on from such a devastating loss, but the Isaacs family's story demonstrates the powerful, often hidden, advantage that comes from refusing to let go, even when the process is arduous and the timeline uncertain. This persistence, while causing immediate discomfort, ultimately led to the recovery of two of three valuable works and a financial settlement that provided some measure of security. The ultimate lesson is that true resolution, and the lasting advantage it brings, often requires enduring significant discomfort and uncertainty over extended periods, a path few are willing or able to follow.

Key Action Items

- Immediate Action (Within 1 month): Conduct a thorough audit of personal or organizational valuable asset security protocols. Identify immediate vulnerabilities, especially for items with significant personal or financial value.

- Immediate Action (Within 3 months): Review insurance policies for valuable assets. Ensure coverage adequately reflects current market values and includes clauses for specialized recovery efforts, not just replacement cost.

- Short-Term Investment (Next Quarter): Document the provenance and condition of all significant assets. This includes photographs, acquisition records, and any relevant historical information that could aid in identification or recovery.

- Medium-Term Investment (6-12 months): Explore options for enhanced security measures, such as specialized storage, alarm systems, or even professional appraisal and cataloging services, if assets warrant it.

- Long-Term Investment (12-18 months): For individuals or organizations with significant collections, establish relationships with art recovery specialists, legal counsel experienced in asset recovery, and relevant law enforcement agencies.

- Strategic Action (Ongoing): Cultivate a mindset that acknowledges the potential for delayed consequences. When facing a loss or a difficult situation, resist the urge for immediate closure if it means sacrificing thoroughness or long-term resolution.

- Personal Development: Develop resilience to tolerate uncertainty and prolonged discomfort. Recognize that significant resolutions, especially those involving complex systems like legal or investigative processes, often require patience and persistence, creating a lasting advantage over those who seek only immediate relief.