Filmmakers' Resilience Through Censorship Fuels Socially Engaged Art

This conversation with Jafar Panahi, a filmmaker operating under immense pressure and censorship, reveals a profound system of resistance rooted not in overt political action, but in the persistent, almost defiant act of creation. The hidden consequence of his work is the subtle yet powerful erosion of authoritarian control through the very act of storytelling, demonstrating that art can be a potent form of dissent when the state attempts to silence it. This analysis is crucial for anyone in creative fields, activism, or leadership who faces systemic obstacles, offering a framework for understanding how sustained, principled action can yield long-term impact and carve out space for truth, even when immediate payoffs are absent and personal risk is high.

The Unseen Architecture of Resistance

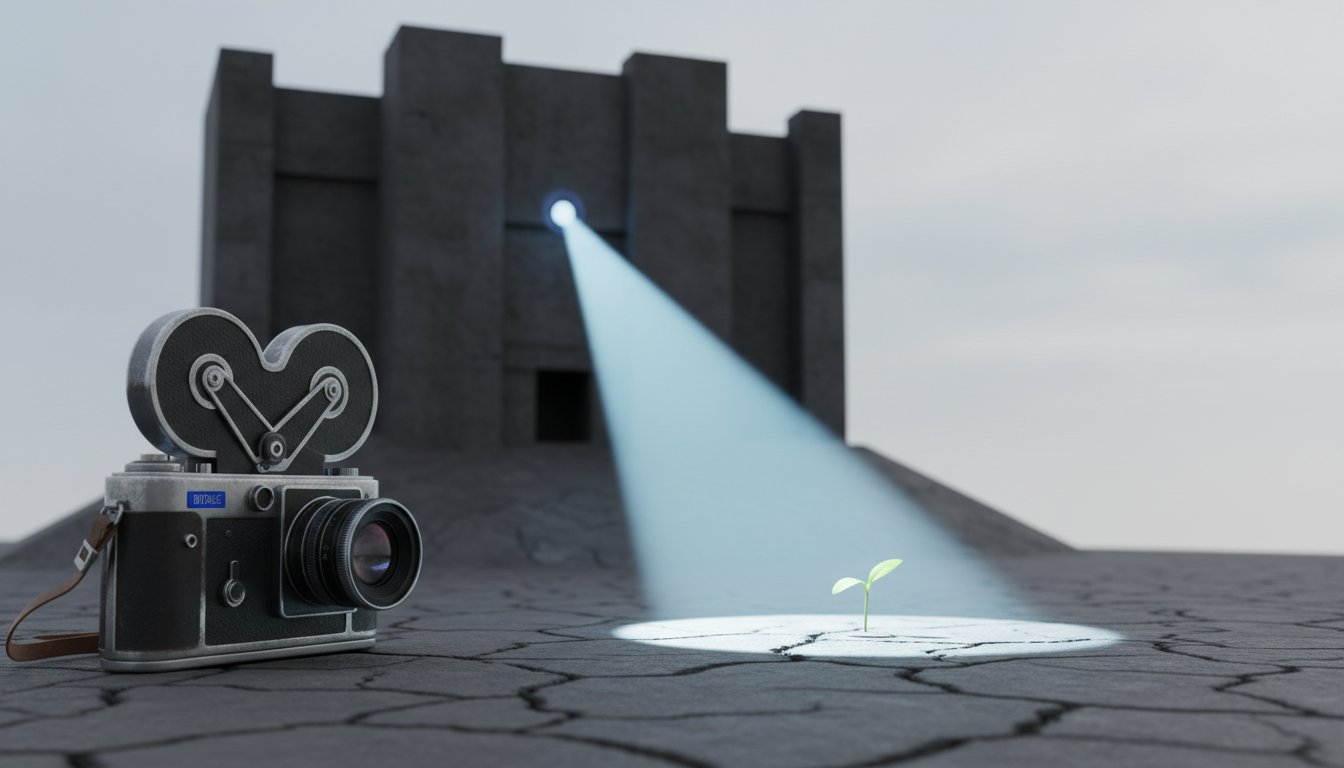

Jafar Panahi’s continued filmmaking, despite facing imprisonment, bans, and state repression, is not merely an act of artistic defiance; it is a sophisticated system of resistance. The immediate consequence of his work is the creation of art that critiques societal forces. However, the deeper, often unseen consequence is the demonstration of a pathway for individuals to operate and create within oppressive structures, thereby undermining the state’s narrative of total control. This is not about a single film, but a sustained practice that builds a quiet, persistent pressure.

Panahi’s approach highlights a critical distinction: the difference between a political film and a socially engaged one. He defines political films as partisan, dividing people into good and bad based on ideology. Instead, his socially engaged cinema focuses on the complexities of everyday life, resisting judgment and allowing characters to reveal their full humanity, even those who have inflicted pain. This method, by refusing to simplify, inherently challenges a regime that thrives on black-and-white narratives and enforced uniformity.

The immediate struggle for Panahi and his collaborators is the logistical challenge of making films without official sanction. This forces innovation, as he notes: "When they put a lot of pressure on you, you also find a way on how to deal with that pressure and how to tolerate it. As we say in Persian, they throw you out the door, you come back from the window. So you will find a way." This isn't just about evading detection; it's about adapting the very form of filmmaking to circumvent limitations. His previous films, like This Is Not a Film (made after a 20-year ban) and Taxi (filmed secretly in a taxi), exemplify this adaptability. The system of repression, by imposing restrictions, inadvertently forces creative solutions that can become enduring methods of operation.

"People who work in these types of underground films, they really don't need to be explained why they're there or what happens in the film. They tend to think to themselves that when society decides to pay a price for something, they will do it collectively."

-- Jafar Panahi

This collective understanding among his crew and actors is a crucial element of his system. They are not simply hired hands; they are participants in a form of social resistance, drawing parallels between their artistic endeavors and broader societal movements, such as women protesting compulsory hijab. This shared commitment transforms the act of filmmaking from a professional pursuit into a form of civic engagement, where the risks are understood and accepted as part of a larger collective effort.

The Cycle of Violence and the Promise of Aftermath

The narrative core of It Was Just an Accident directly confronts the cycle of violence, a theme that Panahi argues is central to understanding societal transitions. The film’s premise--former political prisoners kidnapping a suspected torturer they aren’t entirely sure of--forces a confrontation with vengeance and the question of whether the methods of the oppressor will be adopted by the oppressed.

When asked why this question matters so much, Panahi explains that governments like the one in Iran are not eternal. His focus is on what comes after.

"Because governments with such nature will never last, and there will be an ending point to all of them. And so the question that I had in mind was, what is going to happen afterwards? Is this going to continue? Is this cycle of violence going to bring itself into the next generation, next future, or is it going to be cut?"

-- Jafar Panahi

This forward-looking perspective is where the delayed payoff of Panahi’s work lies. While immediate actions in Iran are met with harsh crackdowns, his films plant seeds of thought about the future, about how societies rebuild and whether they break the patterns of violence. This is a long-term investment in the consciousness of his audience, a strategy that conventional, short-term political action might overlook. The conventional wisdom might focus on immediate protest and immediate demands, but Panahi’s system extends its gaze to the aftermath, asking what kind of society will emerge.

The film's depiction of women, particularly in the context of the "Woman, Life, Freedom" movement, further illustrates this socially engaged approach. Panahi emphasizes showing reality as it occurs. If women are seen without hijab in public spaces after the protests, it's not a political statement for the film, but a reflection of the reality of the society he is depicting. This commitment to verisimilitude, even when it challenges state-imposed norms, is a subtle but powerful way of affirming the lived experiences of Iranians and resisting the erasure of their realities by the government.

Humor, too, plays a strategic role. Panahi notes that while the themes are heavy, humor is integral to Iranian culture and to maintaining realism in his films. He intentionally used humor to draw viewers in, creating a more accessible entry point to the story, with the intention of delivering a profound emotional impact in the final 20 minutes. This is a sophisticated narrative strategy: using lighter elements to build audience connection before delivering a heavier, more reflective experience. It’s a way of making difficult truths palatable, a form of delayed emotional payoff for the viewer, mirroring the delayed societal payoff he hopes for.

The Enduring Power of Presence

Panahi’s insistence on returning to Iran, even in the face of a new prison sentence, is the ultimate expression of his system. He states, "I have the sense of being alive a lot more there than I do here. I know how to enjoy life better over there than I do here." This isn't just about national identity; it's about operating within his element, where he understands the language, the culture, and the nuances of resistance.

"And when we went to Cannes and premiered the film, the same question was asked, why are you going back to Iran? Aren't you scared? But I did go back to Iran because I'm from there, and that's where I know how to do things and how to live."

-- Jafar Panahi

This commitment to presence is the bedrock of his ability to continue making films that reflect Iranian society. His filmmaking becomes a continuous act of bearing witness, a refusal to be silenced or exiled from his own reality. The international recognition--the awards, the Oscar nominations--serves not as an endpoint, but as a tool. It amplifies his voice, brings attention to the films, and creates curiosity, ensuring that the stories he tells reach a wider audience. The "success of a film brings curiosity for the audiences to go and see that film," which is the fundamental goal for any filmmaker, especially one operating under duress.

The system Panahi has built is one where personal risk is a calculated component, where artistic integrity is non-negotiable, and where the long-term impact of storytelling is valued over immediate comfort or safety. It’s a testament to the idea that art, when deeply embedded in societal reality and pursued with unwavering resolve, can become a powerful, enduring force against oppression.

Key Action Items

- Embrace the "Window Strategy": When faced with direct limitations or bans, actively seek alternative, often unconventional, methods to continue your work. This requires creative problem-solving and a willingness to adapt your approach. (Immediate Action)

- Cultivate a Resilient Crew/Team: Foster a shared understanding of the mission and the risks involved. Ensure all collaborators are aware of and accept the potential consequences, creating a collective commitment to the work. (Immediate Action)

- Define Your "Socially Engaged" Stance: Clearly articulate whether your work aims to divide (political) or to explore complexity and human experience (socially engaged). This clarity will guide your narrative choices and resistance strategy. (Ongoing Investment)

- Focus on the "Aftermath": When addressing conflict or societal issues, look beyond immediate solutions or retribution. Consider the long-term consequences and the potential for breaking cycles of violence or oppression. (Requires 3-6 months for strategic integration)

- Prioritize Authenticity in Depiction: Reflect the realities of your society, even when they challenge prevailing norms or state narratives. This commitment to truth, as Panahi does with depicting women's realities, builds credibility and resonance. (Ongoing Investment)

- Integrate Humor Strategically: Use humor not just for levity, but as a tool to build audience connection and make challenging themes more accessible, creating a more profound impact in later stages of the narrative. (Requires 6-12 months for effective application)

- Commit to Your "Place": Understand where you can best operate and have the most impact. For Panahi, this is Iran, despite the risks. Recognize where your roots and understanding provide the greatest strength for your work. (Long-term Investment: Pays off in 12-18 months through sustained output and impact)