Restoring Gut Microbiome Health Requires Diverse Diet and Microbial Reintroduction

TL;DR

- Industrialized diets and antibiotic use can lead to a "deteriorated microbiota" that predisposes individuals to inflammatory and metabolic diseases by altering immune system set points.

- "Reprogramming" the gut microbiome to a healthy state is challenging due to its inherent resilience, often requiring both deliberate reintroduction of beneficial microbes and proper dietary nourishment.

- Consuming a high diversity of fermented foods, such as yogurt, sauerkraut, and kimchi, significantly increases gut microbial diversity and attenuates inflammatory markers in the immune system.

- Processed foods negatively impact the gut microbiome through components like artificial sweeteners and emulsifiers, which can disrupt the mucus barrier and promote inflammation and metabolic syndrome.

- While fiber is crucial, a depleted microbiome may lack the necessary microbes to degrade it effectively, potentially limiting benefits and highlighting the need for microbial reintroduction.

- Over-sanitation of the environment may have gone too far, potentially hindering the immune system's education and balance by limiting exposure to environmental microbes.

- The probiotic supplement market is largely unregulated, necessitating careful product selection based on independent validation or well-designed studies to ensure efficacy and safety.

Deep Dive

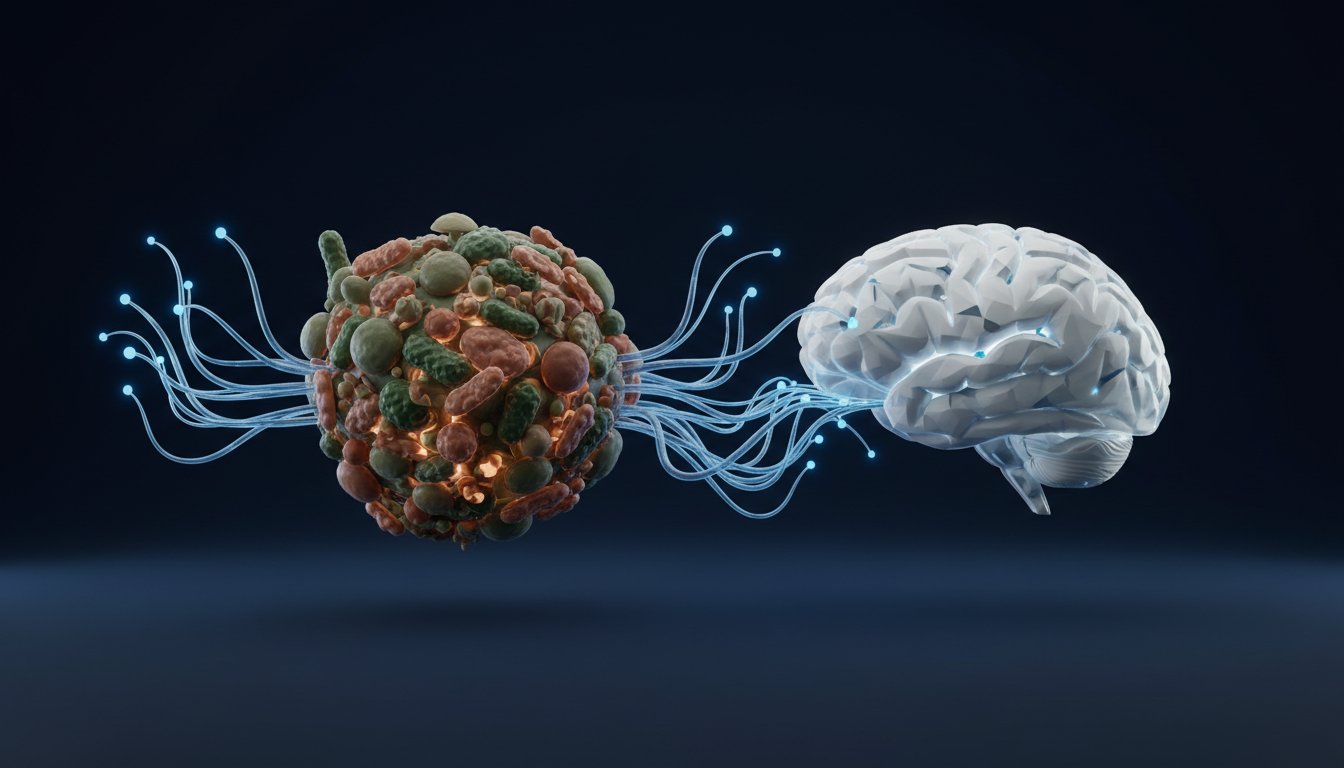

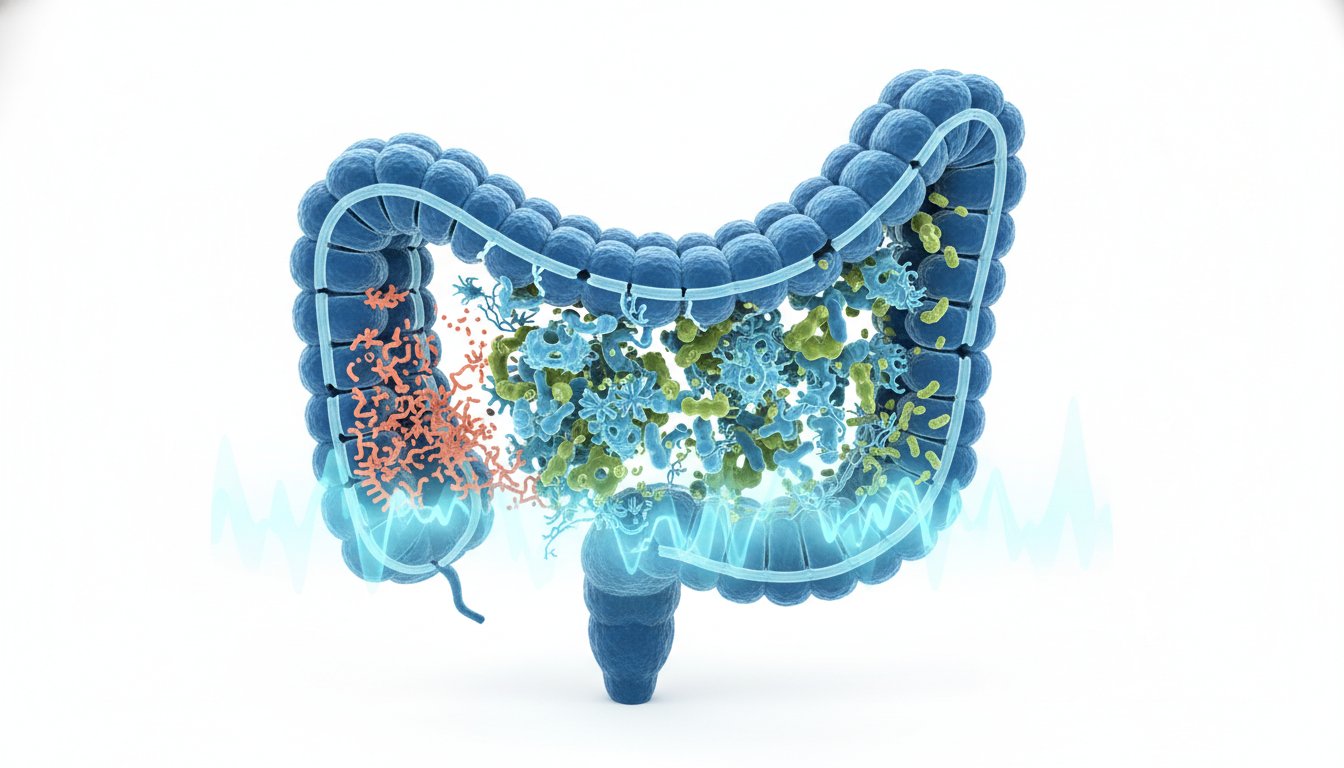

The gut microbiome, a dense ecosystem of trillions of microbes primarily residing in the colon, profoundly impacts human health, influencing immunity and metabolism. While historically viewed as a passive passenger, evidence suggests that perturbations in this microbial community, particularly from antibiotic use and Western-style diets high in fat and processed foods with low fiber, can lead to a deterioration of gut diversity. This loss of diversity is increasingly linked to inflammatory and metabolic diseases prevalent in industrialized societies, suggesting that the microbiome plays a critical role in setting baseline inflammation levels.

The resilience of the gut microbiome presents a significant challenge for intervention; microbial communities often resist change and can snap back to their original state even after dietary shifts. However, prolonged dietary disruptions, especially across multiple generations, can lead to a new, stable, but depleted state from which recovery may be difficult without deliberate reintroduction of lost microbial species. This highlights the critical role of diet, specifically a diversity of plant-based fibers and fermented foods rich in live microbes, in nourishing and potentially restructuring the gut microbiome. Studies show that increasing fiber intake can improve microbiome diversity and reduce inflammatory markers, while consuming fermented foods can similarly enhance diversity and attenuate inflammation, though sugar-laden fermented products should be avoided.

The widespread use of antibiotics and over-sanitation in modern environments may have contributed to a decline in exposure to beneficial microbes, hindering the immune system's proper education and balance. While handwashing remains important, a more nuanced approach to environmental exposure is needed, recognizing that interaction with microbes from the environment can be crucial for immune development. The effectiveness of probiotics is variable due to the unregulated supplement market, underscoring the need for validated products and scientific evidence supporting specific strains for desired outcomes. Similarly, while prebiotics can be beneficial, purified fibers may lead to a reduction in overall microbial diversity by favoring specific bacteria, suggesting that a broad variety of plant-based fibers is generally more effective for fostering a diverse and healthy microbiome.

Ultimately, rebuilding a healthy gut microbiome likely requires a combination of dietary strategies--emphasizing diverse plant fibers and naturally fermented foods--and potentially therapeutic interventions to reintroduce lost microbial species. The current state of an industrialized microbiome, depleted and prone to inflammation, necessitates a proactive approach to gut health, recognizing that restoring balance is a complex but essential endeavor for mitigating chronic disease.

Action Items

- Audit microbiome composition: Identify 3-5 key microbial species or diversity metrics to track for personal gut health status.

- Implement fermented food consumption: Integrate 2-3 servings of non-sweetened fermented foods daily (e.g., yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut) to increase microbial diversity.

- Increase plant-based fiber intake: Aim for 40+ grams of diverse plant fibers daily by incorporating whole grains, legumes, vegetables, and nuts.

- Evaluate artificial sweetener use: Reduce or eliminate artificial sweeteners (e.g., sucralose, aspartame, saccharin) to mitigate negative gut microbiome impacts.

- Track immune markers: Measure 2-3 key inflammatory markers (e.g., IL-6) before and after dietary changes to assess gut-immune system modulation.

Key Quotes

"I think you know just to start off with clarifying terminology microbiome and microbiota quite often are used to refer to our microbial community interchangeably and I'll probably switch between those two terms today the other important thing to realize is that these microbes are um not just in our gut but they're all over our body they're in our nose they're in our mouths they're on our skin basically anywhere that the environment can get to uh in our body which includes inside our digestive tract of course is you know colonized with with microbes and the vast majority of these are in our distal gut and in our colon and so this is the gut microbiota or gut microbiome and um the density of this community is astounding you start off with a zoomed out view and you see something that looks like you know fecal material the digest inside the the gut and you zoom in and you start to you know get to the microscopic level and see the microbes they are just packed you know side to side end to end it's a super dense bacterial community almost like a um biofilm to the point where it's thought that you know around 30 of fecal matter is microbes 30 to 50 so you know it's um it's an incredibly dense microbial community we're talking of um you know trillions of microbial cells and all those microbial cells if you start to get to know them and and see who they are um break out in the gut probably to um hundreds to a thousand species most of these are bacteria um but there are a lot of other life forms there there are archaea which are little microbes that are bacteria like but they're different um there are uh eukaryotes so you know we commonly think of eukaryotes in the gut as um as you know something like uh a parasite but um there are eukaryotes they're fungi there are also little viruses there are these bacteriophages that infect bacterial cells and so -- and and those actually outnumber the bacteria like 10 to one so they're just everywhere there they kill bacteria um and so there's there's these really interesting predator prey interactions but um overall it's just this really dense complex dynamic ecosystem"

Dr. Justin Sonnenburg explains that the terms "microbiome" and "microbiota" are often used interchangeably to describe the microbial communities found throughout the body, not just in the gut. He emphasizes the sheer density and complexity of these communities, noting that microbes make up a significant portion of fecal matter and include bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses. This highlights the pervasive and intricate nature of our microbial inhabitants.

"we know from animal studies that depending upon the microbes that you get early in life you can send the immune system or metabolism of an organism or other parts of their biology in totally different developmental trajectories so what microbes you're colonized with early in life can really change your biology"

Dr. Sonnenburg points out that early-life microbial colonization can profoundly influence an organism's biological development. This suggests that the microbes an infant acquires shortly after birth can set the trajectory for their immune system, metabolism, and other biological functions throughout their life. This underscores the critical importance of early microbial exposure.

"what's healthy for one person or one population may not be healthy for another person or population and i will say that there's no single answer to this but there are some really important considerations perhaps the best way to start talking about this is to go back to um the inception of the human microbiome project which was this um program that that nih started they invested a lot of money in 2008 2009 for um really uh propelling the um field of gut microbiome research it was um becoming evident at that point that this was not just a curiosity of human biology that it was probably really important for our health through those studies we really started to get the image that there is this tremendous individuality in the gut microbiome and um and so it's it's really hard to um start drawing um conclusions after initial pass of that project of what is a healthy microbiome but the other thing that we started to realize at the same time there were studies going on documenting the gut microbiome of um traditional populations of humans hunter gatherers uh rural agricultural populations and um those studies were really mind blowing from the perspective of you know all these people are healthy they're living very different lifestyles and their microbiome doesn't look anything like a healthy american microbiome"

Dr. Sonnenburg discusses the concept of a "healthy microbiome," stating that it is highly individual and context-dependent, varying between populations and lifestyles. He references the Human Microbiome Project, which revealed significant individual variation, and contrasts this with studies of traditional populations. These studies showed that healthy individuals in non-industrialized societies have microbiomes vastly different from those in industrialized nations, challenging the notion of a single definition of a healthy gut.

"it does mean that we need to think carefully about you know restructuring these communities in ways where we can achieve a new stable state that will resist the microbial community getting pulled back to that original state and you know one of the kind of simplest and nicest examples of this is a an experiment that we performed with with mice where we you know we're feeding mice a normal mouse diet a lot of nutrients there for the gut microbiota things like dietary fiber and we switched those mice half the mice to a low fiber diet and we were basically asking the question that you know if you switch to kind of a western like diet a low fiber higher fat diet what happens to the gut microbiota and we saw the microbiota change it lost diversity it was very similar to what we see in in the difference between industrialized and traditional populations but when we brought back a healthy diet a lot of the microbes returned you know it was fairly you know there there was this kind of memory where it went back to very similar to its original state the difference is that when we put the mice on the low fiber high fat diet and then kept them on that for multiple generations we saw this progressive deterioration over the course of generations where by the fourth generation the gut microbiome was a you know a fraction of what it originally was let's say 30 of the species only remained something like 70 of the species have gone extinct or appeared to have gone extinct we then put those mice back onto a high fiber diet and we didn't see recovery so in that case it's a situation where a new stable state has been achieved in that case it's probably because those mice don't actually have access to the microbes that they've lost and we actually know that we did a the control experiment of mice on a high fiber diet for four generations they maintain all their microbes if we take those fourth generation mice with all the diversity and do a fecal transplant into the mice that had lost their microbes but had been returned to a high fiber diet all of the diversity was reconstituted so it was you know so you're your question of like how do we establish new stable states how do we get back to a healthy microbiota if we have taken a lot of antibiotics or have a deteriorated microbiota it's probably a combination of having access to the right microbes and we can talk about what that access looks like it may look like therapeutics in the future there are a lot of companies working on creating cocktails of healthy microbes but it'll be a combination of access to the right microbes and

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "The Good Gut" by Justin Sonnenburg and Erica Sonnenburg - Mentioned as a resource for making microbiome research accessible to non-scientists.

Articles & Papers

- Study on immigrants and gut microbiome diversity (University of Minnesota) - Discussed as evidence that immigrants to the US lose gut microbiome diversity and fiber-degrading capacity over time.

- Study on mice fed a Western diet for multiple generations - Referenced for demonstrating progressive deterioration of the gut microbiome over generations, with a significant loss of species.

- Study on mice fed a high-dose prebiotic on top of a Western diet - Mentioned for observing hepatocellular carcinoma in a subset of mice, raising questions about human applicability.

People

- Dr. Justin Sonnenburg - Guest, professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University, co-author of "The Good Gut."

- Erica Sonnenburg - Co-author of "The Good Gut."

- Chris - Mentioned in relation to a flagship study comparing high-fiber and high-fermented food diets.

Organizations & Institutions

- Stanford University - Institution where Dr. Justin Sonnenburg is a professor and where research on the gut microbiome is conducted.

- NIH (National Institutes of Health) - Initiated the Human Microbiome Project.

- Center for Human Microbiome Studies at Stanford - Home base for dietary intervention research, where studies and information are listed.

Websites & Online Resources

- sonnenburglab.stanford.edu - Lab website for reading more about research.

Other Resources

- Human Microbiome Project - Program funded by NIH to advance gut microbiome research.

- Microbiome/Microbiota - Terms used interchangeably to refer to the microbial community on and in the body.

- Gut Microbiome - The microbial community residing in the digestive tract.

- Western Diet - Characterized as high fat, low fiber, and rich in processed foods, detrimental to gut diversity.

- Probiotics - Live microorganisms intended to provide health benefits when consumed.

- Prebiotics - Non-digestible compounds that promote the growth of beneficial microorganisms.

- Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) - Substances produced by gut microbiota fermentation, such as butyrate, beneficial for colonocytes, barrier function, inflammation, and immune regulation.

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6) - An inflammatory mediator measured in a study.

- Interleukin-12 (IL-12) - An inflammatory mediator measured in a study.

- Scoby - Symbiotic community of bacteria and yeast used to make kombucha.

- Kombucha - A fermented tea drink.

- Sauerkraut - A fermented cabbage dish.

- Yogurt - A fermented dairy product.

- Kefir - A fermented milk drink.

- Kimchi - A fermented vegetable dish.

- AG1 - Nutritional supplement mentioned as a sponsor.

- Joovv - Red light therapy device company mentioned as a sponsor.

- Function - Health testing company mentioned as a sponsor.