The Plenty Paradox: How Abundant Pleasure Fuels Addiction and Anxiety

TL;DR

- Over-reliance on pleasure triggers a dopamine deficit, leading to anxiety and depression as the brain compensates for excessive external stimulation.

- Deliberately seeking mild discomfort or pain, through practices like exercise or cold plunges, upregulates the body's healing mechanisms and increases resilience.

- Self-binding techniques, creating barriers to desired substances or behaviors through time, space, or meaning, are crucial for pausing the impulse-consumption cycle.

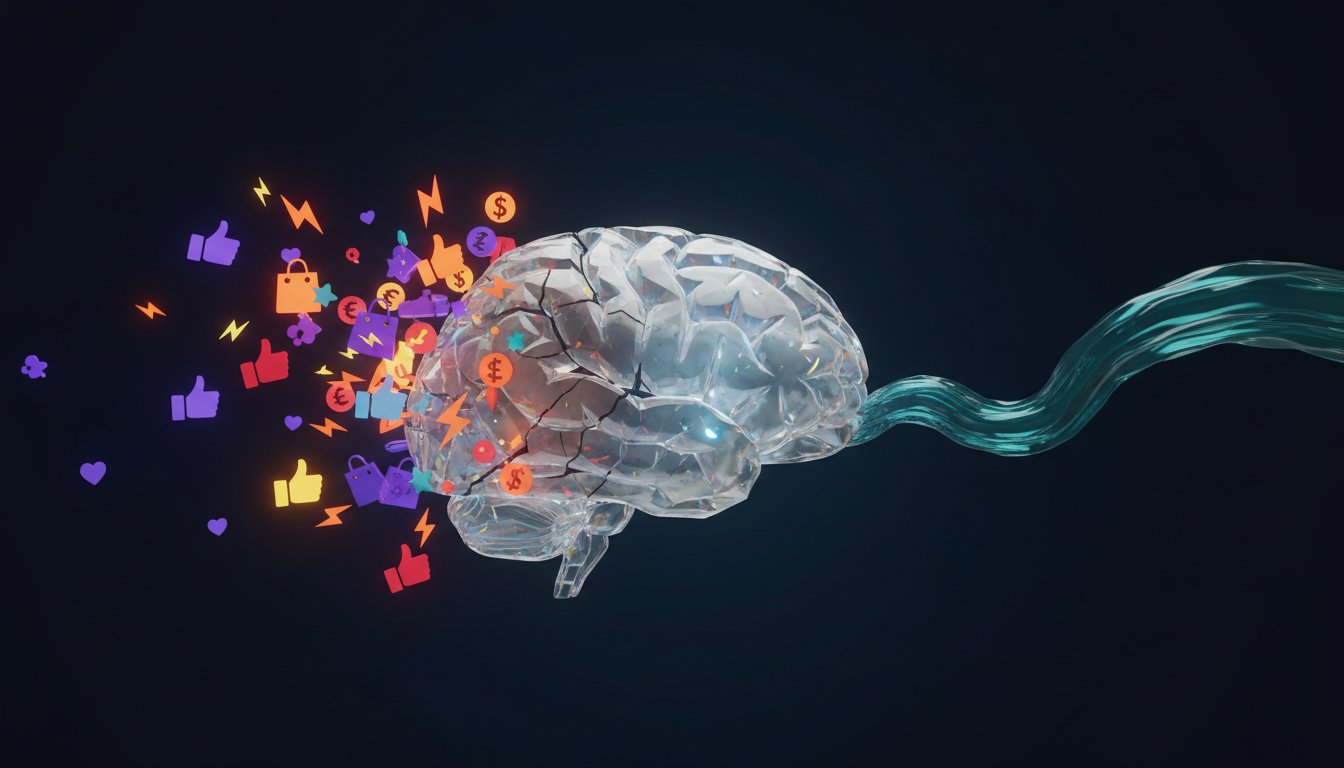

- The modern abundance of highly reinforcing digital media and accessible pleasures makes even healthy behaviors potentially addictive, necessitating conscious navigation.

- Social isolation is a hallmark of addiction, and rebuilding deep human connections through relationships and community is vital for recovery and dopamine regulation.

- Telling the truth, especially about addictive behaviors, is a pivotal practice for maintaining sobriety and recovery by breaching denial and fostering self-awareness.

- Neurodiversity, particularly ADHD, may increase vulnerability to addiction due to impulsivity and potentially lower baseline dopamine firing in reward pathways.

Deep Dive

Our modern world of abundant pleasure paradoxically fuels unhappiness by disrupting the brain's natural balance, leading to increased anxiety, depression, and addictive behaviors. Psychiatrist Anna Lembke argues that this "plenty paradox" stems from our relentless pursuit of dopamine, which forces the brain into a deficit state, compelling us to seek ever-greater rewards. To counter this, Lembke advocates for a deliberate embrace of discomfort and pain, not as punishment, but as a mechanism to reset our hedonic set point and foster resilience.

The core mechanism driving this imbalance is the brain's homeostatic system, a neurochemical seesaw that attempts to maintain equilibrium between pain and pleasure. When we repeatedly trigger pleasure through highly reinforcing substances and behaviors--from social media and online shopping to drugs and alcohol--the brain compensates by creating a dopamine deficit. This deficit manifests as irritability, anxiety, and depression, ironically driving us back to the very behaviors that caused it. Lembke highlights that this cycle is exacerbated by the modern environment, where even typically healthy activities like eating or connecting online can be engineered to be highly addictive through technology. The implication is that simply seeking more pleasure is counterproductive; true well-being requires a conscious recalibration toward discomfort.

Lembke proposes "self-binding" techniques and a deliberate seeking of mild hardship as pathways to regaining balance. Self-binding involves creating barriers--temporal, spatial, or meaningful--between desire and consumption, thereby inserting a pause for conscious decision-making. This could range from removing tempting items from the home to scheduling specific times for activities like social media use. More radically, deliberately seeking out mild pain or discomfort, through practices like exercise, cold plunges, or even prayer, triggers the brain's healing mechanisms and upregulates its own feel-good neurotransmitters. This "paying for dopamine up front" strategy allows individuals to experience pleasure without depleting their neurochemical reserves, fostering greater resilience and overall happiness. Furthermore, Lembke emphasizes that for many, especially those with severe addictions or those addicted to necessary behaviors like eating, external support through community, radical honesty, and structured interventions is crucial, underscoring that addressing addiction often requires systemic and relational solutions, not just individual willpower.

Action Items

- Audit personal digital device usage: Track daily screen time for 3-5 applications (e.g., social media, news, games) to identify potential overconsumption patterns.

- Implement a 4-week abstinence period from one high-reward digital behavior (e.g., specific social media platform, gaming) to observe effects on mood and focus.

- Create a "self-binding" strategy for a identified high-reward behavior by introducing a physical or temporal barrier (e.g., kitchen safe, scheduled usage times).

- Schedule one weekly "discomfort" activity (e.g., cold shower, challenging workout, extended walk) to intentionally engage the brain's pain-pleasure balance.

- Discuss personal observations on digital device usage or a specific high-reward behavior with one trusted individual to gain external perspective.

Key Quotes

"it isn't just our own minds that tell us to choose the path of enjoyment and indulgence our friends remind us that life is short say no to dessert or another round of drinks and someone might call you a spoil sport"

Anna Lembke highlights how societal pressures and norms encourage the pursuit of pleasure and indulgence. This suggests that the drive towards enjoyment is not solely internal but also reinforced by social interactions and expectations, potentially leading individuals to overlook the negative consequences of excessive consumption.

"when we press down hard and often on the pleasure side of the seesaw, triggering bursts of the neurotransmitter dopamine, anna says the brain automatically compensates by pressing down on the other side, producing a dopamine deficit"

Anna Lembke explains the neurological mechanism of homeostasis, where the brain attempts to balance pleasure and pain. She describes how excessive stimulation of the pleasure pathway, through dopamine release, triggers a compensatory deficit, leading to negative states like anxiety and irritability.

"i remember it vividly; it was about 3:00 in the morning on a weeknight, well past the hour I should have been sleeping so that I could be prepared for the next day to come, and I got to a scene where, you know, the characters were using sadomasochistic sex toys, and I just thought to myself, 'How did I get here? What am I doing?'"

Anna Lembke recounts a personal moment of realization about her own compulsive behavior with romance novels. This quote illustrates how even seemingly innocuous activities can become problematic when they interfere with essential functions like sleep and lead to a disconnect from one's values and intentions.

"what i said to her, which is what i say to many people who now come to me wanting help with anxiety and depression and other psychiatric symptoms whom i discover are using high dopamine rewards excessively, is that instead of prescribing them a pill or recommending any kind of psychotherapy, what i invite them to do is to engage in an experiment, which is the dopamine fast for four weeks, in order to reset reward pathways."

Anna Lembke proposes a "dopamine fast" as an alternative to traditional treatments for anxiety and depression, particularly when excessive engagement with high-reward activities is identified as a contributing factor. She frames this abstinence as an experiment to reset the brain's reward pathways.

"the principle is still the same: you know, that they need to get off of that chemical in order to allow their brain to heal."

Anna Lembke emphasizes that regardless of the severity of addiction, the core principle for recovery involves abstaining from the substance or behavior to allow the brain to heal. This highlights the fundamental role of abstinence in restoring neurological balance.

"what we see is that people who use cannabis, that the pot can actually start to do the opposite and make them more anxious and even paranoid over time."

Anna Lembke challenges the common perception of cannabis as solely an anxiolytic, suggesting that chronic heavy use can paradoxically lead to increased anxiety and paranoia. This points to the complex and sometimes counterintuitive effects of substances on mental health over time.

"the more we chase pleasure, the more the brain tries to compensate, leaving us in a dopamine depleted state."

Anna Lembke reiterates the central theme of her work: the paradoxical effect of pursuing pleasure. She explains that the brain's compensatory mechanisms, in response to constant dopamine stimulation, can lead to a state of depletion, which is counterproductive to overall well-being.

"self-binding techniques create both literal and metacognitive barriers between ourselves and our substance or behavior of choice so that we can press the pause button between desire and consumption."

Anna Lembke introduces the concept of "self-binding techniques" as a strategy to manage compulsive consumption. She defines these techniques as creating obstacles, both physical and mental, to interrupt the immediate transition from desire to engaging in the problematic behavior.

"we are living in an unprecedented time of overwhelming access to highly reinforcing drugs and behaviors, such that I think that our existence is going to be reliant upon figuring out how to navigate this world of overabundance."

Anna Lembke identifies the modern environment, characterized by abundant access to highly reinforcing stimuli, as a significant challenge to human well-being. She suggests that navigating this "world of overabundance" is crucial for maintaining health and balance.

"the problem with addiction is that essentially our substance or behavior of choice comes to replace those human connections, and so we move further and further into isolation."

Anna Lembke explains how addiction can lead to social isolation by substituting genuine human connections with the substance or behavior of choice. This highlights the importance of social connection in recovery and overall mental health.

"when we diagnose addiction clinically, we don't do that casually; we talk to patients at length, we talk to their family members, we try to get a full 360-degree view."

Anna Lembke emphasizes that diagnosing addiction is a thorough process that involves extensive consultation with patients and their families, gathering comprehensive information to understand the behavior's impact. This underscores the complexity of addiction and the need for careful assessment.

"the urge to have a dopamine hit is so much stronger, and I've noticed that since I've begun taking medication to treat my ADHD, I find myself less addicted to dopamine producing things like YouTube or Facebook or Instagram."

This quote from a listener suggests a potential link between ADHD and a heightened need for dopamine, implying that effective ADHD treatment might reduce the susceptibility to addictive behaviors driven by dopamine seeking. It raises questions about the role of neurodiversity in addiction.

"schools should have top-down policies where phones are not allowed during school hours, and this top-down policy means that everybody has to be off of their phone; you eliminate the problem of FOMO, or fear of missing out, which is a big driver of what gets kids going back online."

Anna Lembke advocates for strict school policies that prohibit phone use during school hours. She argues that such a top-down approach can alleviate the "fear of missing out" (FOMO) and reduce the allure of highly reinforcing digital devices for students.

"when it comes to something like food, and I think food can be easily analogized also to the technology that's so embedded in our lives, there is on some level not a way to dopamine fast from something that we need in order to survive."

Anna Lembke acknowledges the difficulty of applying dopamine fasting to essential needs like food or deeply integrated technologies. She suggests that for such behaviors, alternative strategies beyond complete abstinence may be necessary for managing compulsive consumption.

"the phenomenon of switching one addiction for another is very well known; it's sometimes referred to as cross-addiction."

Anna Lembke introduces the concept of "cross-addiction," explaining that individuals recovering from one addiction may be prone to developing another. This highlights the underlying vulnerability that can lead to substituting one compulsive behavior for another.

"first of all, I think just being open about it, like Andrea has done, and naming it, can be really helpful. It can bring it into our awareness in a new way

Resources

External Resources

Books

- "Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence" by Anna Lembke - Mentioned as the author's book discussing the balance between pain and pleasure and the neurochemistry of compulsive consumption.

Articles & Papers

- Brown and Shuckit study - Mentioned as a study on alcoholic men with depression that found stopping alcohol resolved depression in 80% of cases.

People

- Anna Lembke - Psychiatrist at Stanford University and author of "Dopamine Nation," discussing compulsive consumption, addiction, and self-binding techniques.

- Martin Buber - Philosopher mentioned for his concept of the "I and Thou" moment in human connection.

- Rob Malenka - Neuroscientist at Stanford whose research shows oxytocin binding to dopamine-releasing neurons.

Organizations & Institutions

- Stanford University - Institution where Anna Lembke is a psychiatrist and researcher.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) - Mentioned as a successful grassroots organization for addiction recovery.

- Narcotics Anonymous (NA) - Mentioned as a successful grassroots organization for addiction recovery.

- Food Addicts Anonymous - Mentioned as a peer support group for food addiction.

- Overeaters Anonymous - Mentioned as a peer support group for food addiction.

Other Resources

- Dopamine Nation - The central concept discussed, referring to the paradox of abundance leading to unhappiness and the brain's compensatory mechanisms.

- Homeostasis - The brain's process of maintaining equilibrium between pain and pleasure.

- Dopamine fast - A technique of abstaining from substances or behaviors that trigger dopamine release to allow the brain to upregulate its own dopamine production.

- Self-binding techniques - Strategies to create barriers between desire and consumption, categorized as time, space, and meaning.

- Hormesis - The science of mild to moderate doses of adaptive pain or discomfort upregulating the body's healing mechanisms.

- I and Thou moment - A philosophical concept describing a deep, fully present encounter between individuals.

- Addictive personality - An older term now referred to as the disease of addiction, acknowledging varying individual vulnerabilities.

- Cross addiction - The phenomenon of switching one addiction for another.

- Neurodiversity - The concept that differences in brain wiring, such as in ADHD, can affect vulnerability to addiction.

- ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) - Mentioned as a condition that may increase risk for addiction due to impulsivity and potential reward insensitivity.