Service Sector Drives Development, Demanding Re-evaluation of Work Value

The service sector, not manufacturing, is now the engine for economic development and middle-class creation, but this shift demands a radical re-evaluation of how we value work. The traditional path of industrialization, once the bedrock of prosperity, is now a dead end for job growth, even in manufacturing powerhouses like China. This forces us to confront a stark reality: the future of work lies overwhelmingly in services. The hidden consequence is that we risk entrenching a two-tiered society where essential service jobs, vital for societal well-being, are relegated to low pay and low status. This conversation is crucial for policymakers, business leaders, and anyone concerned with economic stability and social cohesion, offering a roadmap to navigate this complex transition and build a more inclusive future by elevating the dignity and economic standing of service professions.

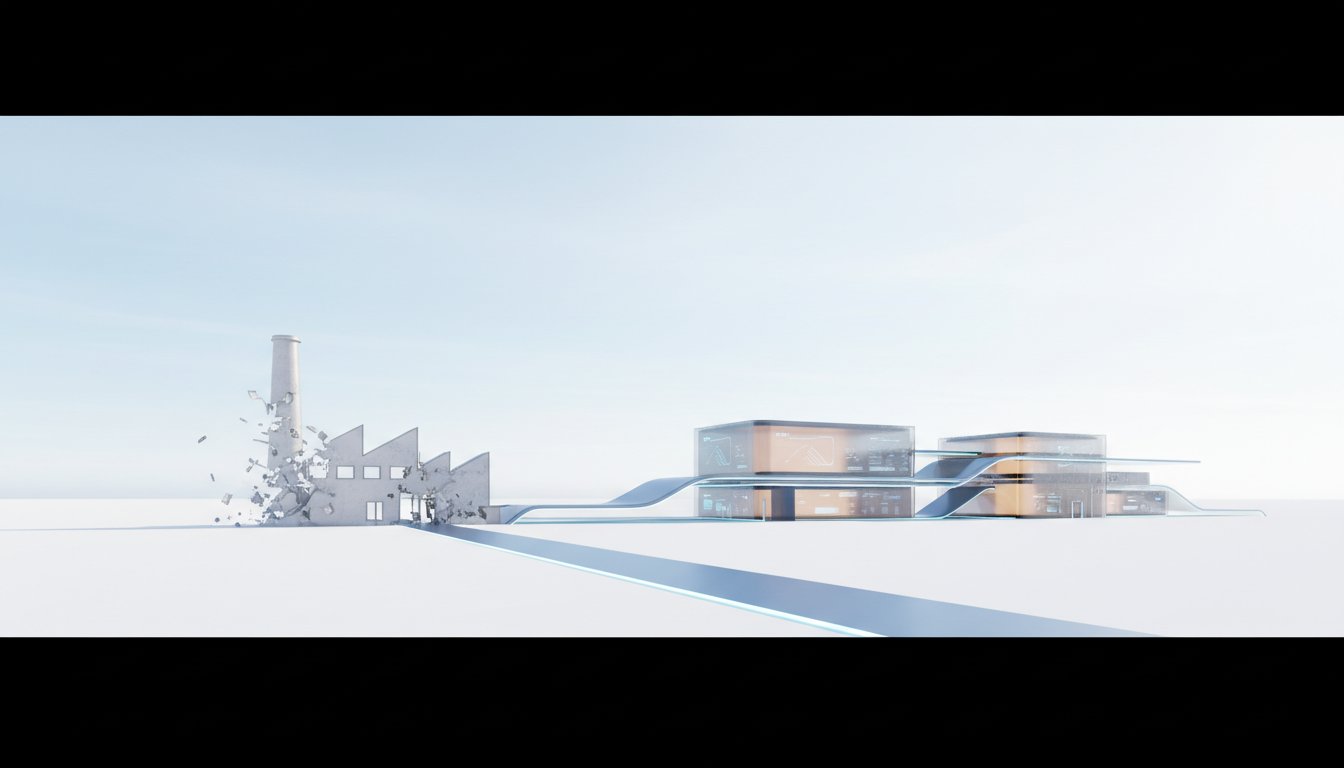

The Unraveling of Manufacturing as the Job Creator

The bedrock assumption for decades has been that manufacturing is the primary pathway to a stable middle class. This narrative, deeply ingrained in economic policy and public perception, is no longer tenable. Dani Rodrik, a leading voice in international political economy, argues with stark clarity that the era of manufacturing-led growth, at least for job creation, is over. The evidence is not just theoretical; it's statistical and undeniable. Even China, the undisputed global factory, has shed tens of millions of manufacturing jobs over the last 15 years. This isn't a blip; it's a systemic shift.

The implications for Western economies are profound. Despite efforts to revitalize manufacturing through industrial policy, such as the CHIPS Act, the numbers simply don't reflect a resurgence in employment. Manufacturing jobs continue to decline as a share of the total workforce. This doesn't negate the importance of manufacturing for national security, innovation, or specific advanced sectors like semiconductors. However, for the explicit goal of generating widespread good jobs and fostering social cohesion, manufacturing is no longer the answer.

"The most telling thing for me as to why manufacturing can no longer be relied upon for generating employment is that China, which is, of course, the undisputed leader in manufacturing and continues to increase production and exports of manufacturing, is losing tens of millions of workers in manufacturing over the last decade or so."

-- Dani Rodrik

This statistical reality forces a pivot. If manufacturing cannot absorb the workforce, where will the jobs come from? The answer, Rodrik contends, is overwhelmingly in the service sector. This is not a preferred outcome, but an inevitable one. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projections confirm this, with the largest projected job growth in non-traded services like long-term care, retail, and food preparation. The challenge, therefore, shifts from revitalizing manufacturing to figuring out how to make these service jobs productive, well-paid, and dignified. The alternative is a future economy built on "bad jobs," a prospect that risks further political backlash and social fragmentation.

The Service Sector: A New Frontier with Hidden Traps

The transition to a service-based economy presents a fundamental challenge to our understanding of capitalism and work. Historically, manufacturing jobs offered a path to prosperity because they were leverageable through capital investment and technological innovation, leading to increased productivity and, eventually, higher wages. Service jobs, particularly personal services, often lack this inherent leverage. A nurse providing care or a massage therapist performing a service cannot easily be "leveraged" in the same way a factory worker can be augmented by machinery. This one-to-one nature of many service roles raises questions about scalability and wage growth.

However, this picture is more nuanced than it appears. Technological advancements are increasingly impacting the service sector, boosting labor productivity in areas like retail, logistics, and even healthcare. Platforms like Uber and Amazon have demonstrated how technology can intensify work and extract maximum surplus, but they also hint at the potential for increased productivity. The critical question is who controls these innovations and how the benefits are shared. If new technologies are solely controlled by platforms or large corporations, they can lead to job intensification and precarious gig work, rather than improved conditions and higher wages.

"The challenge here is that manufacturing has been historically very easy to deploy new innovations and new technology. That's why, in fact, when we're talking about manufacturing losing jobs, it's because it's becoming so productive, that is that you're replacing workers with robots or machinery, and labor productivity goes up, but output goes up, but employment goes down."

-- Dani Rodrik

This dynamic creates a potential trap: increased productivity in services might lead to job displacement rather than wage growth, as seen with the transition from Blockbuster to Netflix. The key differentiator lies in the type of service job. Some, like warehouse work at Amazon, are becoming highly systematized and Taylorized. Others, particularly those requiring a human touch like long-term care, are less susceptible to immediate automation. The future hinges on developing technologies that are "labor-friendly"--enhancing worker agency and sophistication--and ensuring that productivity gains are broadly shared, not just captured by capital. This requires deliberate policy choices and organizational innovations, moving beyond a simple market-driven approach.

The Unseen Value of Essential Work: Elevating Service Jobs

The core dilemma of a service-based economy is how to assign value and dignity to jobs that society relies upon but historically undervalues. Essential roles in long-term care, home healthcare, and other personal services are becoming increasingly critical, especially with aging populations, yet they are often relegated to "bottom rung" status. The conversation grapples with whether these jobs can be elevated through increased pay and societal respect, or if their inherent nature and historical perception make this impossible.

Historically, good jobs have been underpinned by three pillars: productivity gains, worker collective bargaining power (unions), and government mandates (like minimum wages). While productivity is increasing in some service sectors, traditional unionization is more challenging due to the dispersed nature of service work. This points to the need for innovative approaches to collective bargaining and a conscious effort to re-evaluate the societal worth of these professions.

"The question is whether we can make service jobs productive, well-paid, and dignified, or whether we resign ourselves to an economy built on bad jobs."

-- Dani Rodrik

The example of medicine, where healers were always valued, or even journalism and certain crafts like sculpting, suggests that job prestige can evolve. However, these often started with a baseline of respect. The challenge is to elevate jobs that were historically considered low-status. This requires more than just market forces; it demands a societal recognition that certain jobs are essential and deserve commensurate compensation and respect, regardless of their "leverageability" in traditional economic terms. This is where government intervention, through targeted subsidies, support for new organizational models, and a redefinition of what constitutes a "good job," becomes paramount. It’s about consciously shaping a future where societal needs are met with dignified and sustainable employment.

Key Action Items

-

Immediate Actions (Next 1-3 months):

- Champion Local Economic Development: Advocate for and support local initiatives that foster cross-sectoral partnerships between government, businesses, and educational institutions to develop regional economic plans focused on service sector growth.

- Invest in Skills for Service Roles: Support and expand programs that offer targeted training and upskilling for high-demand service jobs, particularly in long-term care, healthcare support, and skilled trades.

- Promote "Good Jobs" Metrics: Encourage businesses and policymakers to adopt metrics that go beyond simple job creation to include wages, benefits, worker agency, and job satisfaction in evaluating economic development success.

-

Medium-Term Investments (Next 6-18 months):

- Explore Labor-Friendly Technology Development: Support research and development initiatives, potentially modeled on ARPA, focused on creating technologies that enhance worker capabilities and autonomy in service sectors, rather than solely focusing on automation.

- Pilot Sectoral Bargaining Models: Experiment with and pilot models of collective bargaining beyond traditional unionization, such as sectoral wage agreements, to improve conditions in service industries.

- Re-evaluate Service Job Compensation: Initiate studies and public discourse on how to better compensate essential service workers, considering models that reflect societal value and need, not just market leverage.

-

Longer-Term Strategic Investments (18+ months):

- Develop a National Service Sector Strategy: Create a comprehensive national strategy that prioritizes the growth of productive, well-paid, and dignified service jobs as the primary engine for economic development and middle-class creation.

- Foster Regulatory Experimentation for AI Governance: Encourage diverse approaches to regulating AI, allowing for experimentation at national and regional levels to discover effective models for ensuring equitable distribution of benefits and mitigating risks.

- Advocate for Societal Value Re-evaluation: Launch public awareness campaigns and policy initiatives aimed at elevating the societal perception and respect for essential service professions.