The Saver Mindset: Aligning Capital with Life's Time Horizons

The "Saver" Mindset: Unpacking Cullen Roche's 10 Principles for a Portfolio That Serves Your Life

This conversation with Cullen Roche, founder and chief investment officer of Discipline Funds, fundamentally reframes the act of investing from a speculative endeavor to a disciplined process of allocating savings. The core thesis is that most individuals are not true "investors" in the economic sense of funding future production, but rather "savers" reallocating existing capital. This distinction, seemingly semantic, reveals hidden consequences: it shifts the focus from trying to "beat the market" to the more achievable and sustainable goal of building a portfolio aligned with personal time horizons and consumption needs. Those who grasp this reframe gain a significant advantage by sidestepping behavioral pitfalls like performance chasing and panic selling, leading to a more robust and life-aligned financial future. This is essential reading for anyone seeking to move beyond the often-misleading allure of "investing" and embrace a pragmatic approach to wealth building.

The Illusion of the "Investor": Why You're Really a Saver

The prevailing narrative around investing often conjures images of shrewd stock pickers or daring entrepreneurs. Cullen Roche challenges this directly, positing that for the vast majority, the act of buying stocks and bonds on secondary markets is not "investing" in the economic sense of funding new production, but rather a sophisticated form of saving -- reallocating your existing capital. This distinction is critical because it dismantles the myth of "beating the market" as the primary objective. When you understand you are a saver, the focus shifts from outsmarting others to the prudent, long-term process of aligning your capital with your life's needs across different time horizons. This shift is not merely jargon; it’s a strategic pivot that inoculates against the behavioral biases that plague most portfolios.

"The reason I like this concept is because from an application perspective, the idea of investing, I think sometimes is sort of viewed as something sexy or like a get-rich-quick kind of endeavor, whereas allocating your savings is fundamentally boring. It's a prudent process, it's a long-term process."

This reorientation combats the inherent human tendency to be one's own portfolio's worst enemy. Roche highlights that fear during market downturns and the equally potent fear of missing out (FOMO) during bull markets are the primary drivers of destructive behavior. Chasing performance, often associated with hot sectors like AI, can lead investors to chase risk rather than genuine returns. The data supports this: over 95% of active managers underperform simple index funds over a 20-year period. This isn't a failing of intelligence, but a testament to the difficulty of consistently outsmarting a complex market. The "fun money" allocation, while seemingly harmless, can balloon and create significant behavioral challenges. The emergence of strategies like the 351 exchange offers a novel way to manage concentrated stock risk without triggering immediate, crippling capital gains taxes, allowing for a rebalancing into diversified ETFs.

"Often times, people chase performance, and that ends up being one of the worst things people can do because often times you're just chasing risk, you're not actually chasing return."

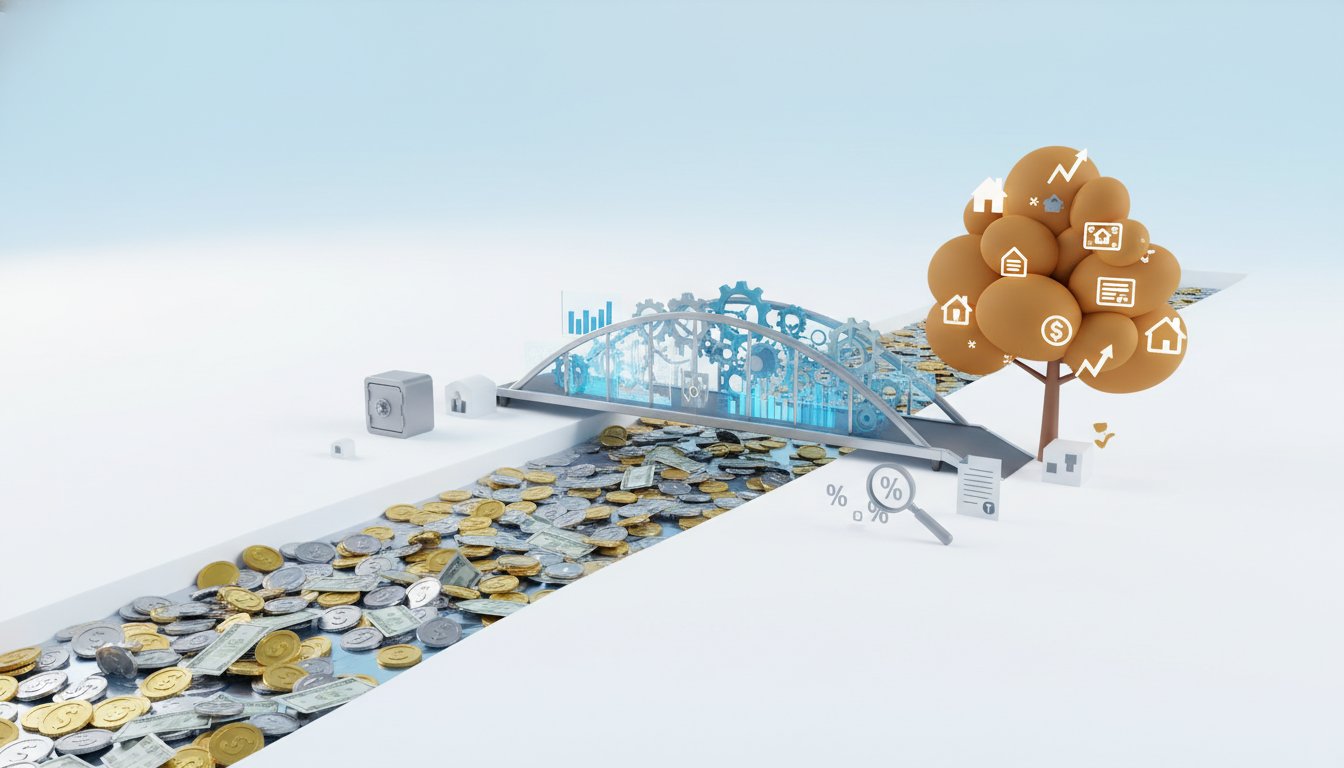

The concept of diversification, often lauded as "the only free lunch," becomes paramount. However, Roche and the podcast hosts acknowledge the increasing difficulty in finding truly uncorrelated assets in our interconnected world. This is where strategies like trend following, which can go long or short and capture uncorrelated return streams, become more interesting. The disparity in returns across asset classes, such as the US versus foreign markets or even within commodities like gold, underscores the persistent need for diversification. The risk of "diworsification" -- creating an overly complex portfolio with too many holdings that resemble a simple index fund but with higher costs and management overhead -- is a real danger, often perpetuated by an industry that profits from complexity.

The Temporal Conundrum: Aligning Assets with Life's Timeline

A significant portion of Roche's framework revolves around the "temporal conundrum" -- the challenge of aligning assets with specific time horizons. Traditional investment styles, focusing on factors like market capitalization or growth vs. value, often miss the mark for the average person who thinks in terms of life events: a vacation next summer, a child's college in 10 years, retirement in 30. Roche advocates for a "defined duration" strategy, essentially an asset-liability matching approach. This involves quantifying future expenses and matching them with specific financial instruments that mature at the appropriate time.

"People think in time horizons. I was working with somebody, they had an incredibly complex financial plan, and all the wife cared about was the ability to remodel the bathroom next year. It was like the only thing she cared about. She desperately wanted this new bathroom. And when I modeled out the financial plan and I showed her that, 'Hey, we've got a six-month Treasury bill that is perfectly matched to your bathroom remodel next year,' it was like the only thing she cared about."

The intermediate time horizon (roughly 3-10 years) presents a particular challenge. It's too long to be held in cash and too short to reliably weather stock market volatility without risking a significant loss just when the funds are needed for a major expense like a house down payment. This is where careful construction, potentially blending asset types to create a "blended time horizon," becomes crucial. The principle that "past performance is not indicative of future returns" is a critical reminder here. The future is unlikely to mirror the past, especially with rapid technological shifts. Therefore, relying solely on historical data for long-term projections is inherently flawed.

The concept of "real, real returns" is central to setting realistic expectations. Gross returns often cited in financial media fail to account for inflation, taxes, and fees -- the actual costs that erode purchasing power. Understanding these net returns is vital for sustainable wealth building. Furthermore, risk is reframed from academic volatility to the "uncertainty of lifetime consumption," encompassing inflation, fees, and longevity risks, particularly unpredictable healthcare costs. Managing liabilities, by understanding needs versus wants and maintaining a healthy lifestyle, is presented as a powerful complement to asset management.

Key Action Items:

- Embrace the "Saver" Identity: Shift your mindset from "investor" aiming to beat the market to "saver" prudently allocating capital. This reduces behavioral risk. (Immediate)

- Quantify Liabilities and Time Horizons: Map out your future expenses and align them with specific timeframes (e.g., 0-2 years, 3-10 years, 20+ years) to guide asset allocation. (Immediate)

- Utilize the 351 Exchange (If Applicable): Explore this strategy to rebalance highly concentrated stock positions into diversified ETFs without immediate tax consequences. (Short-term: 3-6 months)

- Prioritize Diversification: Actively seek uncorrelated or low-correlation assets, understanding that true diversification is an ongoing effort. (Ongoing)

- Focus on "Real, Real Returns": Always consider inflation, taxes, and fees when evaluating investment performance. Aim for net returns that preserve purchasing power. (Ongoing)

- Build a "Defined Duration" Portfolio: Match specific pools of money to specific future expenses, creating certainty for near-term needs and freeing up capital for long-term growth. (Medium-term: 6-12 months)

- Set Realistic Expectations: Base your financial plan on conservative assumptions for inflation and investment returns to avoid disappointment and maintain discipline. (Immediate)